According to musician-turned-scientist Daniel J. Levitin, most people would not consider studying music through the lens of science. In his book This Is Your Brain on Music, Levitin attempts to overcome this barrier and analyze how the human brain responds to music. As a former musician and sound engineer himself, Levitin puts his own experience with the music industry to use in explaining how our brains interpret, process, and respond to music.

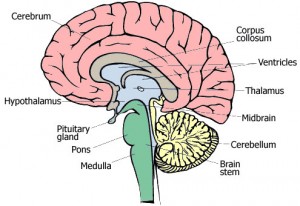

The title of the book suggests an eventual epiphany or bold conclusion about music and human psychology. However, Levitin’s approach is surprisingly conservative: He simply guides the reader through an elementary analysis of music and how it triggers responses in the brain. For example, Levitin describes how the brain’s cerebellum interprets rhythm, a process that allows us to tap our feet in time with a song. Similarly, he correlates emotional responses to music with the amygdala, pitch distinction with the A1 auditory cortex, and so on.

The content is not revolutionary, but enriching nevertheless for musicians and non-musicians alike. With the help of Levitin’s occasional analogies (correlating musical intervals with “jumps”) and popular music references to the likes of Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles, even a novice reader can examine music with a new perspective.

Admittedly, the book’s presentation and style are sorely lacking. The first two chapters are a rundown of musical theory that are presented in a block-text format, only sporadically interspersed with analogies. Once past the first two chapters, ideas often felt incomplete. The feeling of coming full circle was rare at best, and Levitin’s abrupt transitions from simple to complex topics are jarring — the reader barely has time to understand the different types of sound, for instance, before Levitin launches into the physics of music. Furthermore, tangential distractions are peppered throughout the book. A discussion on the difference between the mind and brain seems off-topic, and Levitin provides no connection to the book’s main message before reverting to an explanation of music theory.

Finally, many of Levitin’s anecdotes seem to serve no purpose in illuminating the reader, and instead appear self-serving. An entire chapter devoted to meeting biologist Francis Crick only addresses neuropsychology and music concretely in the last five pages, while the majority of the chapter is filled with personal accounts that have little relevance to the book.

This Is Your Brain on Music takes a promising idea and attempts to explain it to a broad audience. To find this book an entertaining read, the dedicated reader must get through the first two chapters and sift through tangled discussions in search of a few enlightening ideas. For most, however, this endeavor is not worth the effort. The disjointed style and organization detract too much from the subject at hand, leaving a powerful topic only somewhat explored.

Rating: 2/5