More than 1.7 million Americans have amputated limbs. Losing a limb is traumatic in itself, but the physical amputation is not the end of the struggle. Ninety percent of amputees experience phantom limb syndrome, meaning they are haunted by continued sensation in the amputated area.

This mysterious sensation manifests in a variety of ways. Two-thirds of patients describe a feeling of an insatiable itch. For others, the mere itch escalates to perpetual tenseness, a nagging feeling of discomfort, or even extreme stabbing pain. Painkillers are of no use when the limb is not really there. Nor does phantom limb syndrome fade with time — many victims live with it for the rest of their lives

The mystery of phantom limbs has baffled scientists for centuries. Although modern theories are leading to potential treatments, there is no strong consensus among neuroscientists about what causes this unique syndrome. While earlier theories focused on psychology and surgical error, arguments have been made recently for neuronal plasticity, or the ability of neurons in the brain to adjust their function. At large, phantom limbs remain an unsolved mystery.

Early theorists on phantom limbs believed that pathological denial caused the artificial sensation. Many patients underwent years of psychotherapy to no avail. This psychological theory added insult to injury — on top of tremendous disorienting pain, victims had to deal with the feeling that they were somehow to blame for it. The next dominant theory to emerge about the origin of phantom limbs was equally harmful to patients. When limbs are amputated, severed nerve endings remain in the stump. These raw edges, scientists theorized, might continue to be stimulated post-surgery. The frayed nerve endings could misfire, relaying false information back to the brain about a non-existent limb. With this mindset, surgeons attempted to alleviate phantom limb pain by shortening the amputee’s stump, hoping to remove problematic nerve endings. These efforts were a complete failure; most patients continued to experience phantom limb pain.

Dr. V.S. Ramachandran, currently working at UC San Diego, is the renowned neurologist responsible for the most prominent modern theory on phantom limbs. He points to the somatosensory cortex, part of the brain that receives and interprets sensory signals from different parts of the body. In one experiment, Ramachandran used Q-tips to touch different parts of an amputee’s face. The patient realized that when Ramachandran touched his cheek, he also felt sensation in his phantom limb. Ramachandran claims that phantom limbs arise when the neurons that previously received signals from the amputated limb begin to overlap with the neurons responsible for other parts of the body. Neurologists used to think that the brain was a static organ, but new evidence illustrates neuronal plasticity, the idea that neurons in the brain change and adapt to new circumstances.

Still, Ramachandran’s theory is imperfect, and several critics have voiced concerns. Dr. Tamar Makin of Oxford University claims to have found no evidence of cortical remapping through her research. Even more condemning, she has also discovered that cortical representations of the missing limb are stronger, not weaker, in patients who suffer phantom limb pain. This means that these neurons are not converted for use in other tasks.

Phantom limb syndrome has eluded both explanation and treatment for centuries. Explanation remains a mystery, but treatment is within closer grasp. Though he has not managed to convince the entire scientific community with his neuronal plasticity theory, Ramachandran has been successful in curing some patients of their phantom limb pain.

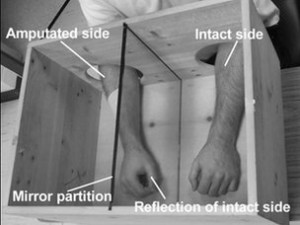

For one patient, who had an inexplicable feeling that his phantom arm and hand were clenched tightly, Ramachandran designed a cardboard box with two arm holes and a mirror in between — an impossibly simple-looking contraption. Looking at the intact arm and its reflection in the mirror creates the illusion that the patient has two fully functional arms. Ramachandran instructed the patient to clench and release his intact fist while looking into the mirror box. To the patient’s surprise, his long-endured phantom pain subsided immediately.

Ramachandran believes that the mirror box illusion creates major neurological conflict between visual and tactile sensory information. The brain is overwhelmed by the conflicting signals, and the phantom limb disappears. But not all neuroscientists agree about why or how this treatment works, and just as many disagree about the cause of phantom limb syndrome itself. The key to understanding this phenomenon remains trapped within the complex labyrinth of the human brain.