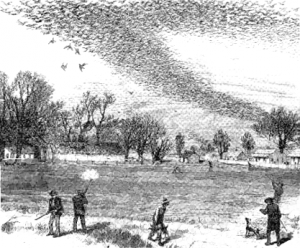

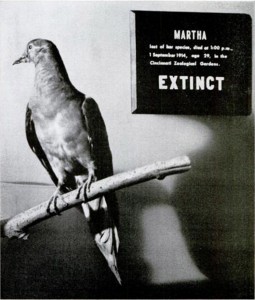

Passenger pigeons once ruled the skies of North America. With over 2 billion pigeons counted in 1860, they were the largest population of birds on the continent. However, by 1890, their numbers had dropped to a few thousand. The last surviving passenger pigeon, Martha, died on September 1, 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoo.

The extinction of the species grew out of the advancements of the late nineteenth century. The technology-enabled human population boom was accompanied by an increased demand for land and food. Deforestation to make way for towns left large populations of passenger pigeons homeless. With the advent of new technology such as trains and the telegraph, hunters were able to track and kill large numbers of pigeons for food.

The existence of passenger pigeons was extended for a few more years at zoos, which provided a safe, albeit artificial, home for the lingering few birds. However, the birds were not meant to live in captivity. Breeding decreased significantly and the last surviving pigeon was infertile.

Now, scientists are trying to find a way to bring back these long-lost birds with cutting-edge biotechnology advancements. The project, called “The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback,” is spearheaded by researchers from the Paleogenomics Lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz, through The Long Now Foundation’s Revive & Restore initiative. This group devotes its efforts to rescuing endangered and extinct species with genetic techniques.

The researchers hope to clone passenger pigeons, but they face one major obstacle: they do not have any passenger pigeon DNA. The remaining passenger pigeons are preserved in museums, but they do not have DNA that can be used for cloning. So, scientists plan to use the next best thing, the DNA of band-tailed pigeons, a close living relative of the passenger pigeon. Scientists will use the DNA of museum specimens to determine which sequences in the passenger pigeon’s genome are unique and implement these modifications in the genome of the band-tailed pigeon.

A successful experiment will result in viable eggs that can hatch into passenger-pigeon chicks. However, there is much uncertainty regarding the feasibility of the project. There is no guarantee that the scientists will be able to determine which genes distinguish the passenger pigeon from its relatives and the actual cloning may not be successful — birds have never been cloned successfully before.

From a long-term perspective, cloning one passenger pigeon will be a small step in the long journey to bringing back a thriving population. Scientists must also look back in history to the time before their extinction to determine what environment and social structure the birds need to succeed.

The project’s timeline extends over the next 13 years. Research will be carried out until 2016 to generate a close match to the passenger pigeon genome, and cloning will aim to hatch passenger pigeon chicks by 2022. With careful breeding and studying, researchers will begin to release the newly restored species to the skies in 2027. If the researchers’ plan is a success, our skies could look very different in a mere 15 years.