For a long time, psychologists have known that sleep is integral to learning, as it allows certain parts of the brain to relive experiences from wakefulness and to ingrain them in memory. Recently, scientists have stumbled upon a new concept — honey bees may also require sleep for information processing.

Since the 1980s, researchers have known that all insects, including bees, have a form of rest that closely resembles sleep. Just as humans do, bees require rest, despite significant differences in brain size and levels of mental functioning between the two species. In an attempt to explain the same sleep requirement, researchers Ada Eban-Rothschild from Stanford University and Guy Bloch from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem examined the effects of sociability on the sleeping habits of bees. They found that increased sociability resulted in more hours of sleep for their honeybees.

The fact that sleep is important for memory and learning has important implications on human health and wellness. One study on sleep in mice found that animals restricted from deep slumber, and thus unable to unconsciously relive their day’s events, had difficulty remembering past experiences. Sleep may be necessary for memory reconsolidation, and this phenomenon extends to humans: Researchers at UCLA found that academic performance is notably improved when students get a good night’s sleep rather than cram until the early hours of the morning. Eban-Rothschild and Bloch’s research on honeybees can also be applied to humans on the level of sociality, and it adds to our scientific understanding of the mysterious world of dreamland.

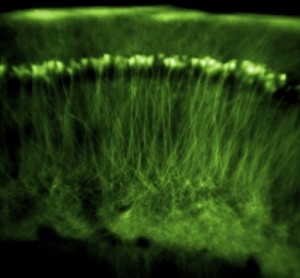

When a young honeybee enters the hive, it finds itself lost in a whirlwind of tens of thousands of wriggling, furry bodies speaking to each other through dances and message-carrying chemicals. To see if this environment had an effect on sleep, Eban-Rothschild and Bloch allowed some young bees to mingle with the hive while isolating a few bees in the lab. They found that the young bees that were allowed to interact with the rest of the hive slept on average five more hours immediately after leaving the hive than did the bees that were kept in isolation. An even more interesting finding was that the bees did not need to physically touch the other nestmates. Bees placed in the hive but separated from others by mesh netting exhibited the same sleeping pattern as the other sociable bees. Those that spent time alone and were kept from mingling not only slept less, but were unable to interact with other hivemates afterwards.

While the sleeping pattern of bees may not rewrite history in itself, it offers a new perspective on the effects of sociability in others species, including our own. The increased need for sleep in social bees may come from the immense amount of information that their brains must process and store in memory from merely interacting with the other hivemates. Perhaps this level of information processing requires a good night’s sleep.

Could this requirement apply to humans as well? It may be that those who venture out and interact with the rest of society acquire more information simply through these conversations. Social humans might then require more sleep or some form of rest in order to ingrain the day’s events in memory.

While a direct comparison cannot be made between the sleeping patterns of bees and those of humans, there certainly exists an interesting link. Scientists hope to examine the factors that necessitate the extra sleep in bees — whether it is the interactions that happen inside the hive or outside with other bees, and which encounters allow for the transfer of information.

Until further studies are published, maybe college students can blame sleep deprivation for their antisocial tendencies.