When we look up at the sky, we may wonder what lies above. Equally intriguing is when we look down at the earth, wondering what lies below. Long before we could study it — centuries before, in fact —Earth’s core had captured human imagination. In 1936, Inge Lehmann finally discovered that our planet has a solid heart — an inner core of iron, surrounded by a liquid shell. A recent discovery, however, forces us to reevaluate this simple picture. According to scientists at the University of Illinois, the earth’s core is not a uniform sphere, but a two-layered one, and each half is distinct in composition.

The first depictions of our planet’s interior were made not by scientists, but by storytellers and philosophers. Greek mythology describes the fiery hell of Tartarus, buried deep below the ground, while the Vikings imagined an underworld full of ice. Later, in the 19th century, theories of a hollow Earth became popular; explorers advocated trips to the North Pole, where they hoped to find portals to the empty core. Jules Verne based one of his most famous novels, Journey to the Center of the Earth, on these fanciful ideas. In his interpretation, the planet is filled with prehistoric life that survived there outside the reach of civilization.

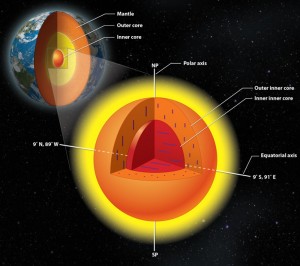

Scientists, of course, have long known that Earth is anything but hollow. They questioned what the core was made of, and what properties it might have. Eventually, studies of earthquakes put these questions to rest. Scientists studied seismic waves to understand the nature of the rock through which they moved. The evidence they gathered revealed the planet’s inner structure: a concentric series of layers, ranging from the rocky crust at the surface to the solid inner core, with the liquid outer core and the slowly-flowing mantle in between.

This multi-layered picture of the earth’s core has been broadly accepted for nearly a century, but recent evidence from the University of Illinois forces us to rethink it. Using the most accurate seismology equipment available, professor Xiaodong Song and his team performed a study on the aftershocks of earthquakes, using them like an ultrasound to probe the structure of the earth. For the most part, Song’s findings agreed with conventional wisdom — but not when it came to the inner core. The earth’s core is not, Song’s group realized, a homogenous iron sphere. Rather, it contains two distinct layers, each with unique properties and magnetic orientations.

The differences between the inner core’s two halves are striking. Both are made of iron, but the outer layer’s particles point north-south, while the inner layer’s particles point east-west. This finding was surprising, as the earth’s core was likely uniform during its formation. Sometime during the planet’s early history, part of its center must have flipped 90 degrees, for reasons yet to be explained or understood. It would take a massive geologic event to cause such a deformation, which likely played a large role in Earth’s evolution.

“The fact that we have two regions that are distinctly different may tell us something about how the inner core has been evolving,” Song told the BBC. “Something very substantial happened to flip the orientation of the core.”

The mysterious event also had effects other than polarity changes. The inner core’s two layers reflect seismic waves in a different manner, indicating that their crystal structure might be different. This discovery, too, is evidence for some kind of prehistoric impact, though it raises more questions than answers. For decades, we have thought of the planet’s center as well-understood, only to find that it still conceals many mysteries. Deep beneath our feet, a two-layered ball of iron provides fascinating territory for exploration.