Mark Essig lights up when he tells the unlikely story of how 19th century hog drives in the Blue Ridge Mountains created a complex infrastructure of taverns, roads, and pig statues across North Carolina. This story fascinated Essig and led to his 2015 book Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig, an account of the changing human relationship with pigs over time. It starts with humans raising hogs along the Nile, and takes readers all the way up to the modern U.S. pork industry.

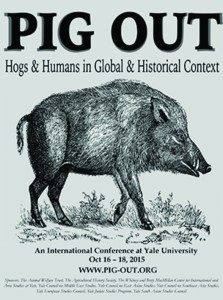

This past October, Essig was a speaker at the “Pig Out” conference at Yale, where he and other porcine academics gathered to discuss all things swine.

Fully titled “Pig Out: Hogs and Humans in Global and Historical Context,” the conference drew academics from far-reaching fields — from religious studies, to agriculture, to sociology, to genetic engineering. These experts gathered in New Haven to discuss how we can better understand human society — both today and in historical context — by focusing on the pig.

Diverse issues are affected by the pig in a social, cultural, and scientific context. Debates over vegetarianism and ethical animal slaughter, for example, would benefit from an interdisciplinary conversation, which is exactly what the Yale Pig Out conference hoped to achieve.

One subject Essig touched upon was environmental issues, and the fact that they cannot escape the porcine narrative, especially as the industrial age has changed the role of pigs. Wooden fences were replaced with concrete boxes that more effectively contain hogs. The very definition of livestock as food was abstracted as big agriculture herded animals into factories not unlike car factories that were springing up around the same time. The rise of big agriculture had ramifications for our relationship with pigs — generally speaking, we think of pigs today more as food and less as sentient creatures. Essig argues that this mirrors our altered interaction with the environment as a whole, which is one way that the pig story sheds light on changes in human society.

“Culture plays a role in decisions about what to eat and the way we use meat,” Essig said. “There are a lot of ways to get sustenance. The particular decisions we make about the meats we eat say a lot about how we organize ourselves as society.”

No aspect of modern American agriculture, which is increasingly becoming industrialized, is “terribly pretty,” Essig added. “Pork is the worst.”

Pigs are the smartest creatures that humans eat on a large scale. They are unique livestock in several key ways — less mobile, yet far more self-sufficient than any other livestock, and capable of foraging and surviving on their own in almost any environment, urban or rural. Understandably, humanitarian concerns have been raised as companies capture pigs in tight cages and dose them with antibiotics, effectively eliminating their self-sufficiency. Furthermore, factory farming sometimes releases environmental toxins. Methane from livestock is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions.

Essig describes the role of government regulation of the meat industry as “a lack of regulation.” If anything, the U.S. government has been a promoter of the meat industry, and authorities have been known to turn a blind eye to environmental damage in favor of higher profit, he said. In this way, the fate of the pig in the industrial age reflects the key environmental and humanitarian concerns of our time.

The pork industry through the ages is a case study of industrialization and the environment. If these issues go unaddressed, future consequences may be dire. The future of the pig mirrors the future of our societal decision on how to interact with our environment. As Essig put it, “food is about identity,” and the human relationship with the pig shows how much that identity has evolved.

The October conference looked to history as much as it discussed modern day controve

rsies related to the pig. “The number of pig bones found at historical sites correlates with political changes; there were more pig bones when the political structure was weaker,” Essig said. Observations like this further demonstrate how pigs might illuminate secrets of humans’ historical past. Pigs were a calculated choice by ancient social systems, as they were animals that could be more easily organized than other livestock, such as cattle, sheep, or goats. Subsistence villages on the margins of empires benefited greatly from the pig. Once again, pigs paint a picture of the political, economic, and environmental climate at any given time.

Other key speakers at the Yale conference included renowned food journalist Colman Andres, animal warfare advocate Bob Comis, and Greger Larson, director of the paleogenomics department at the Oxford School of Archaeology. The event was sponsored by the Yale agrarian studies program.