The state of being “deaf” cannot be simply classified as a medical condition; individuals with hearing loss comprise a community with a rich culture, known as “Deaf” (with a capital “D”).

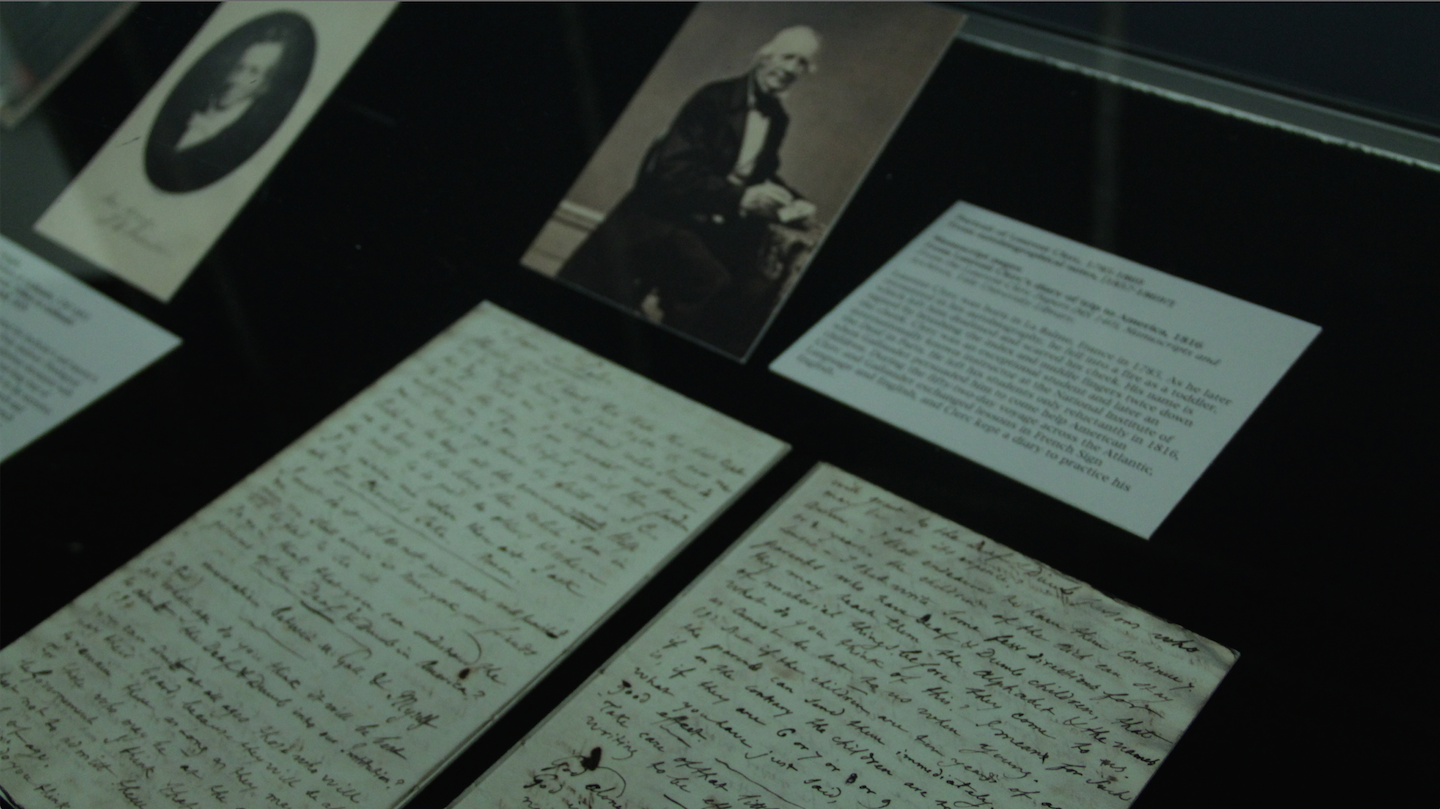

The idea that Deafness is an identity, rather than a debilitating disease, is the subject of an exhibit, “Deaf: Cultures and Communication, 1600 to the Present” at the Yale School of Medicine. The exhibit, curated by Yale Ph.D. candidates Katherrine Healey and Caroline Lieffers, is located in the Harvey Cushing and John Hay Whitney Medical Library. Featured items include historical documents and books, spanning such topics as stigmas behind deafness and the development of American Sign Language (ASL), one of the core components behind Deaf identity in the United States.

On the medical front, the exhibit traces the significant advancements researchers have made in understanding specific causes and types of hearing loss over the past 150 years. Some of these hearing issues are temporary, arising from the common cold or a buildup of earwax. Others are more lasting, originating from changes in certain genes related to hearing and balance.

Assistive technologies have also undergone quite a transformation. In the 19th century, aural surgeons used instruments such as a Eustachian catheter to clean the inner ear of any excess fluid. In the 20th century, physicians turned to electric devices as possible cures for deafness. However, these early hearing aids were bulky and heavy, until advances in technology allowed for more portable devices.

The exhibit, however, does not solely focus on deafness in the clinical space; it also celebrates Deaf culture and community. A Yale alumnus, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, founded the first permanent school for the Deaf in North America in the 19th century. Gallaudet’s son was also a pioneer in higher education for the Deaf, as he founded the first Deaf college. Such schools are sites of language development in the Deaf community. Though ASL is commonly used, many schools also communicate using Total Communication Philosophy. This style of teaching encourages several forms of communication, such as body language, lip-reading, and speech.

“Culturally Deaf people resist the medical model of deafness as disability,” Healey said. “We hope doctors, medical students, visitors, and any Yalies who see the exhibit will better appreciate the multiple meanings of deafness,” she added.