For fifty years since its discovery, many scientists regarded the Grolier Codex as a forgery. Looters unearthed the codex, an ancient Mayan book, from a cave near Chiapas, Mexico. The looters flew Josué Sáenz, a pre-Columbian art collector, to Chiapas, keeping Sáenz in the dark about the cave’s location by hiding the plane’s compass with a cloth. After some bargaining, Sáenz wrote them a check on a secret airstrip in the pouring rain and returned to Mexico City, manuscript in hand.

Despite its bizarre origin story, the Grolier Codex is not only genuine, but also is the oldest surviving book in the Americas.

“I’ve seen fifty or sixty or seventy fakes in my life…and I took a look at the Grolier Codex, and said, ‘This is a [genuine] Venus calendar and a completely unknown codex,’” said Michael Coe, Charles J. MacCurdy Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Yale University. Coe has studied pre-Columbian art for over forty years; he has even worked for the IRS to determine the authenticity of art pieces in court cases.

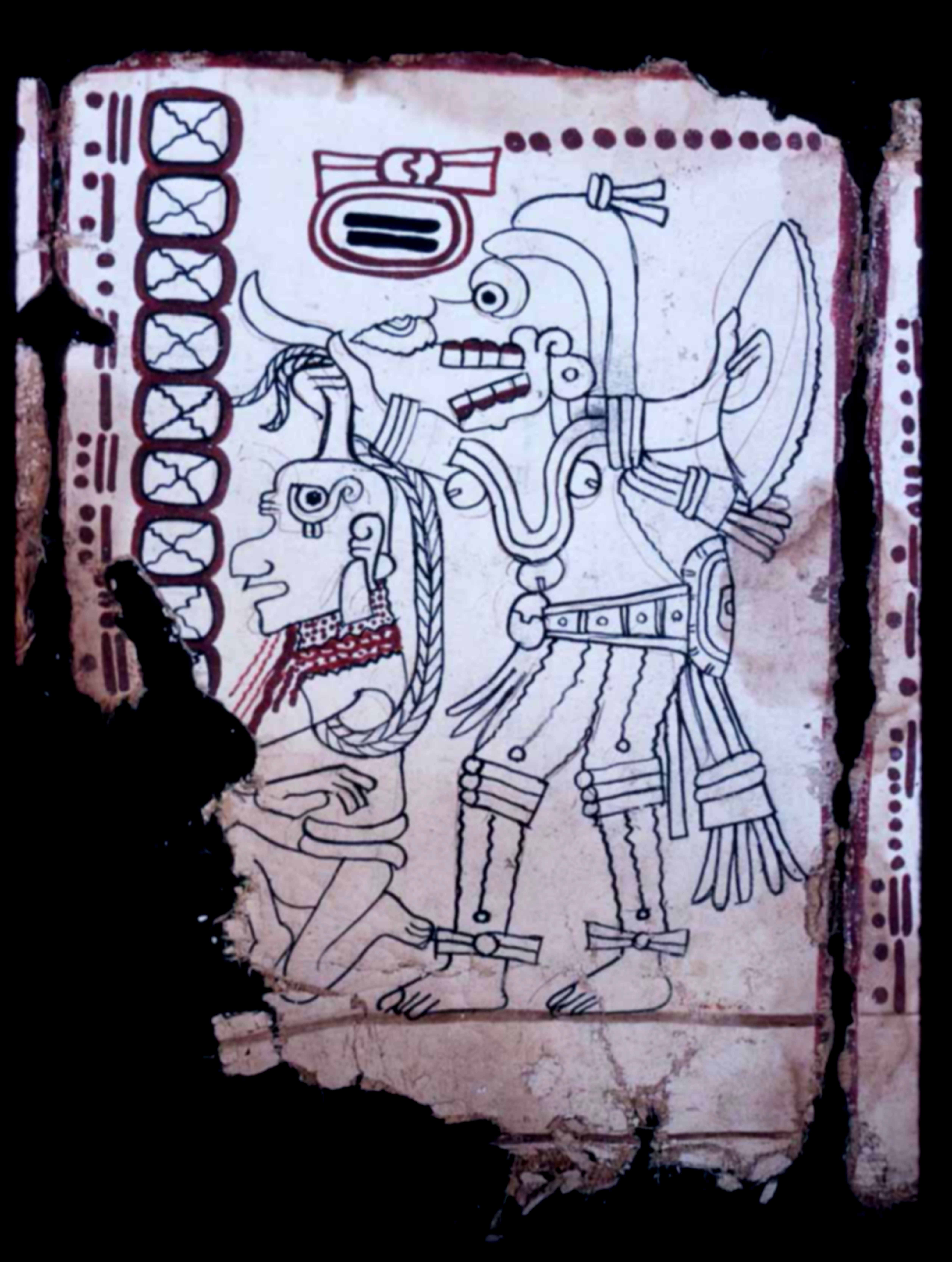

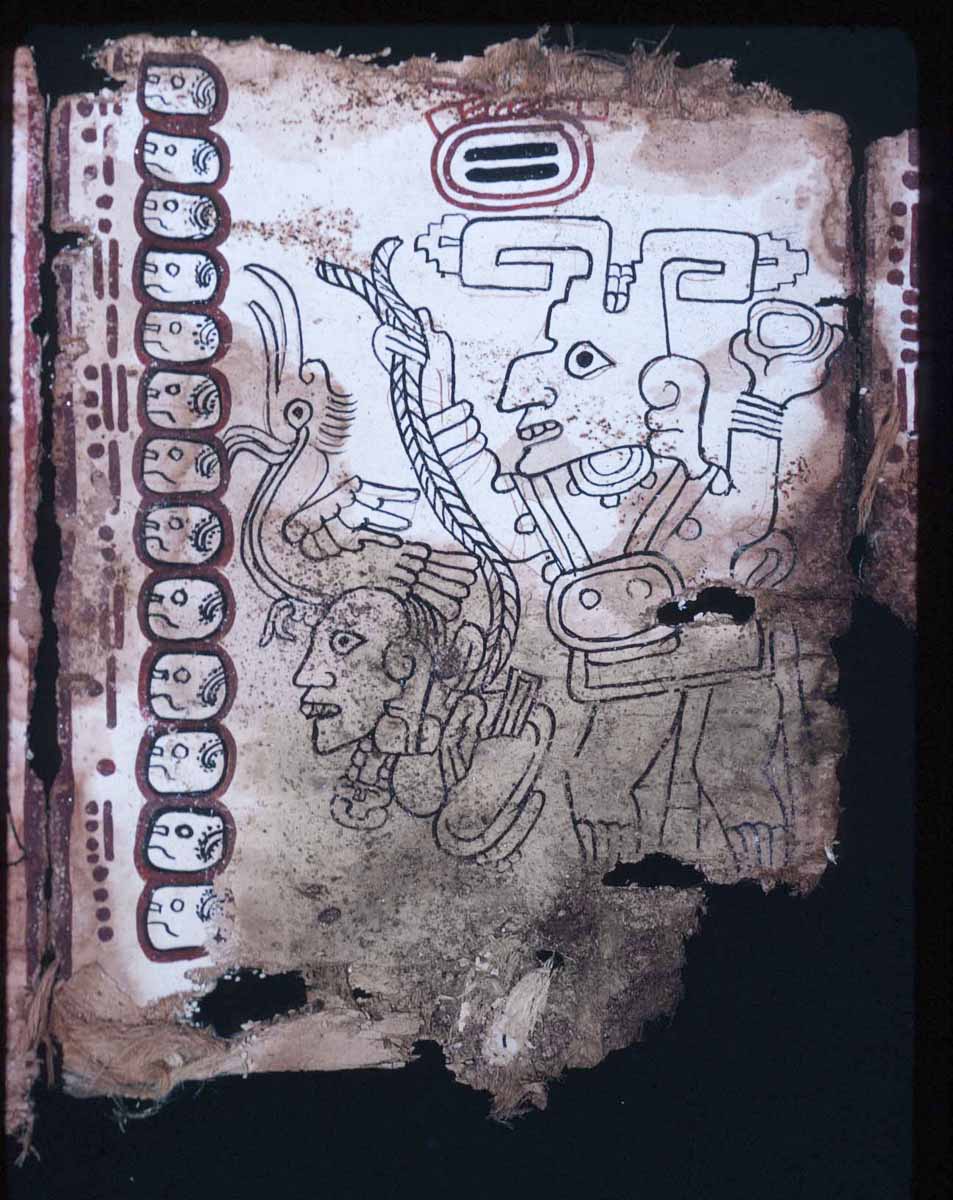

Coe visited Sáenz in the late 1960s, and he convinced the collector to lend him the manuscript for display at the Grolier Club, a bibliophilic society in New York. Soon after, Coe published a paper on the manuscript, bringing the newly named Grolier Codex to the attention of academics. It was not well received. Several papers appeared refuting the codex’s authenticity, citing its differences from the three known Mayan codices. The Grolier Codex’s prevalence of illustrations, relative lack of hieroglyphics, and dubious origins were all causes for concern.

But Coe has maintained since the beginning that the manuscript is authentic. A recent review article in Maya Archaeology 3 presents abundant evidence to this point. Coe coauthored this paper with Stephen Houston, Professor of Anthropology at Brown University, Mary Miller, Professor of History of Art at Yale, and Karl Taube, Professor of Anthropology at the University of California-Riverside.

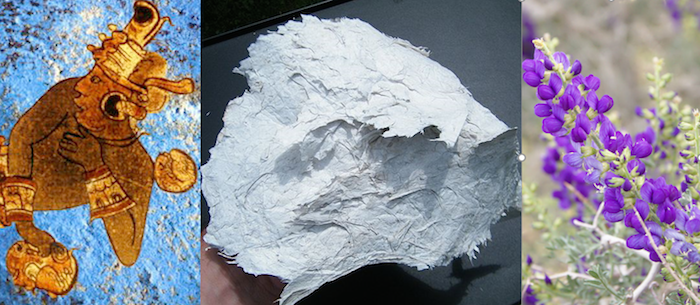

One scientific analysis highlighted in the review discusses what Coe considers the book’s clearest indicator of authenticity—its age. Radiocarbon dating shows that the book’s amate, or bark paper, dates to the thirteenth century. This is the same age as other carbon-dated objects, including a ceremonial mask and a knife, which the looters found in the cave.

But what if the looters had found blank amate from the thirteenth century and had simply drawn on it? Not possible, Coe said. Several Mayan deities depicted in the Grolier Codex, such as one split-headed Mountain God, were not described until decades after the codex’s discovery.

Furthermore, ink analyses did not detect any modern pigments in any of the Grolier Codex’s three ink colors. A 2007 paper by Jose Luis Ruvalcaba, Professor of Physical Science at Universidad Nacional Autónoma in Mexico, and his colleagues determined the elemental composition and structure of the inks using particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE). Each of the ink colors was exposed to an ion beam, causing them to emit wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation that matched the spectra of certain elements. They found that the red was a high iron, hematite-based dye, and the black was carbon. This would be expected of a genuine codex, since these inks were common in the Maya world and were used in other pre-colonial Mesoamerican documents.

The blue of the codex has eluded characterization. If the codex were genuine, it would be the well-known Maya Blue. Maya Blue has been widely used in Mayan mural painting and has been found in trace amounts on other Maya codices. “It’s a very complicated blue, the best in the world—it never fades. It’s a mixture of a clay mineral [known as palygorskite] and an organic indigo, from the indigo plant,” Coe said.

PIXE analysis on the blue ink by Ruvcalba was inconclusive in its detection of organic indigo, though the elements’ spectra match those of palygorskite. Since other materials share the same elements as palygorskite, it is not possible to prove definitively the presence of Maya Blue in the Grolier Codex. Despite this, scientists did not successfully synthesize Maya Blue in a laboratory until the 1980s. “There isn’t any way a faker could have known how to make it,” Coe said.

Now that Coe and his team have gathered enough evidence to show that the codex is authentic, they hope that the insights it can provide into Mayan life will not face further contention. Like the other three codices, the Grolier Codex is an astronomical calendar that tracked planetary motions to record the passage of time and assist priests with planning rituals. “The man who made it was probably a priest with some astronomical knowledge, in a temple of a small kingdom,” Coe said. The Grolier Codex aims to predict the movement of the planet Venus for a period of at least 104 years. All the featured gods are holding weapons, suggesting that, contrary to the prevailing knowledge of the 1960s, the Mayans associated all the twenty named days of the Venus calendar with ill tidings.

The codex is a fusion of Mayan tradition and traditions of other Mesoamerican civilizations. It was written in the Early Postclassic period, when several regions increased their intercommunication and linked their traditions of art and styles of writing. The amate of the Grolier Codex was coated with gesso, also known as plaster of Paris, which was also common in Central Mexican manuscripts. Furthermore, the number system used in the codex combines both aspects of Maya-style bars and dots, as well as the rings of the Mixtec-style, another Mesoamerican civilization. “By then, all the great cities had all collapsed. Out of that comes [a blending of civilizations] a couple hundred years later; the remnants are in the Grolier Codex,” Coe said.

After decades of holding the unpopular opinion that the codex is genuine, Coe said he is glad that experts are starting to change their minds. “It’s nice to be vindicated,” Coe said, adding, “I never once changed my mind in these 43 years. I knew it was good.”