Every person has a “microbiome” living on the surface of their skin—a diverse mini-ecosystem of microorganisms, or small living things that are individually undetectable without a microscope. Recent research has revealed that patients with eczema—a chronic condition marked by rashes and itchy skin—have a markedly different skin microbiome compared to those without.

In a perspective article published in Nature Microbiology, Yale dermatology instructor and post-doctoral fellow Ian Odell and professor of Immunobiology Richard Flavell discussed the findings of researchers working at the Genome Institute of Singapore. The research article by Kern Rei Chng and his team compared the abundance of all the microbes on the skin of normal individuals to those with eczema.

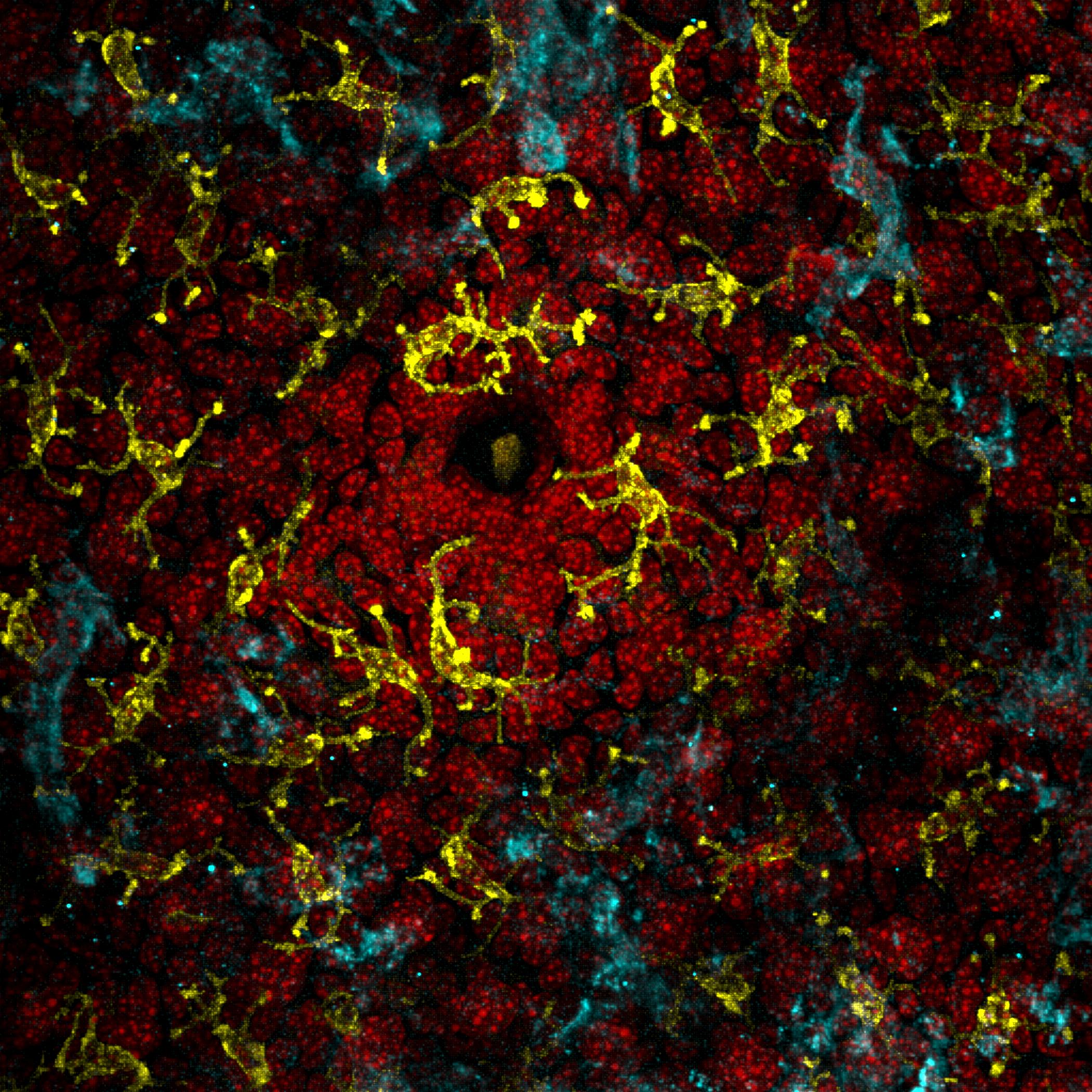

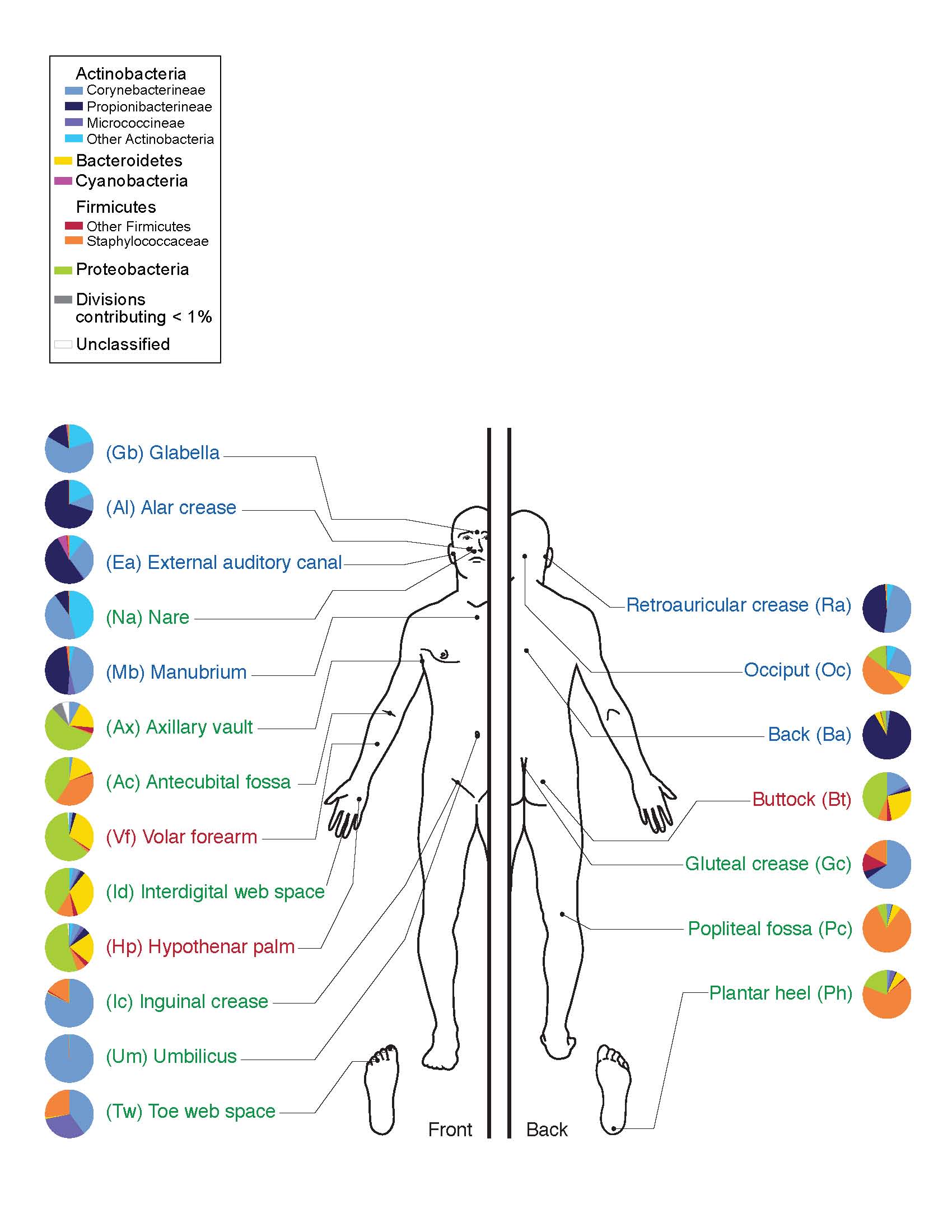

For humans with and without eczema, the skin is home to a vast array of microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi. Different areas of the skin provide various types of habitats, depending on their location, number of folds, thickness, and amount of hair and glands. Different types of microbes preferentially occupy these diverse niches. These mini-ecosystems depend on a delicate balance of conditions, just like macro-ecosystems such as coral reefs. Disruption to this balance within the skin lead to skin conditions and infections.

Chng’s team hypothesized that these mini-ecosystems may play a major role in the manifestation of eczema symptoms. In order to explore this idea, Chng studied the skin microbiome of adult patients with eczema. According to Odell and Flavell, the most effective technique that Chng and his team used to obtain data on the patients’ microbiomes was repeatedly applying and peeling off a strip of tape on their skin 50 times. This method saturated the piece of tape with skin cells and microbes, allowing it to become a snapshot of an individual’s skin microbiome.

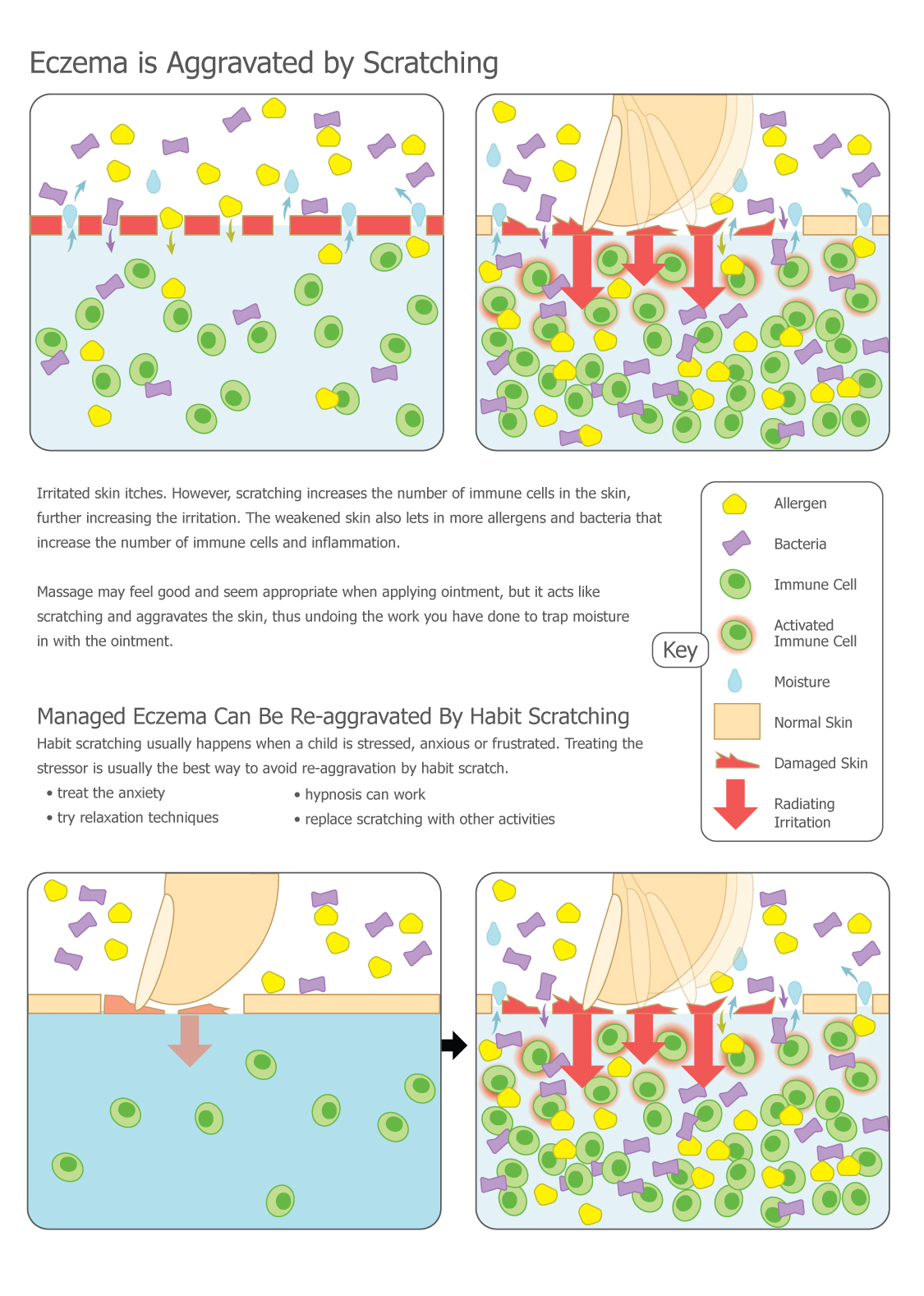

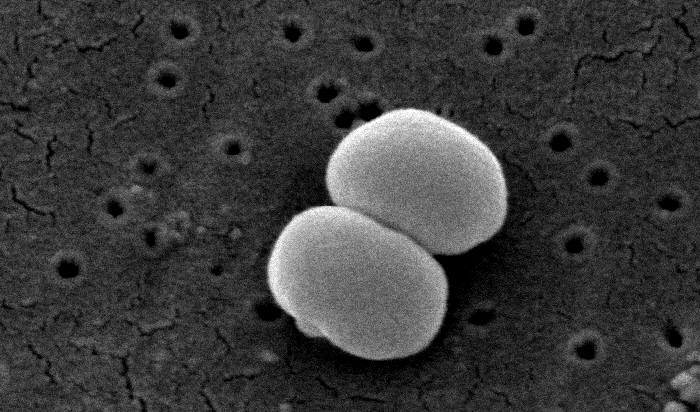

Typically, patients with eczema experience periods called flares when the rash worsens, and periods called remissions when the skin improves or even seems to recover completely. It was previously discovered that during flares most of the bacterial diversity on the skin is lost and predominated by Staphylococcus aureus. In Chng’s study, patients with eczema had their skin microbiome sampled during one of these remission periods in order to measure baseline differences that may predispose them to eczema. Samples were collected via the tape-stripping method from patients with eczema and patients without eczema, and then the DNA was extracted and sequenced. Chng’s team used new sequencing technology that allowed them not just to identify the microbes, but also to study their abilities to modify their skin environment.

They found that patients with eczema have bacteria that produce anti-Staphylococcus compounds and trigger a more inflammatory immune response, suggesting that these bacteria were able to thrive in this skin micro-environment due to their ability to inhibit S. aureus. Importantly, the unique bacteria present in eczema were the same as those identified in a similar study performed in Washington, D.C., telling us that the phenomenon occurs in multiple countries and across races and genetic backgrounds.

As of late 2016, the correlation between increased levels of Staphylococcus and eczema is well-established; however, scientists are still investigating whether increased levels of Staphylococcus cause eczema, or if the skin conditions associated with eczema are simply favorable to these bacteria. Currently, crippling Staphylococcus—often with antibiotics—works as a treatment for eczema, but there are many other types of bacteria that also would be affected by these antibiotics, so this treatment is non-specific.

“Ideally in the future we will have more targeted therapies to modify a patient’s microbiome, such as against S. aureus, or [to] target parts of the immune system that control what bacteria live on the skin,” Odell said. A new hope for eczema patients thus includes therapeutics that target a particular species of microbe, which may help to reduce the harmful members of these individuals’ microbiomes while also promoting the survival of the beneficial members.