Left unchecked, global temperatures will rise by five degrees in the next two hundred years. While heat may be welcomed by cold New Englanders, this temperature increase will have damaging effects on the planet, such as rising of oceans and submergence of coastal cities. In a recent publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Yale Professor of Forestry and Environmental Studies William Nordhaus addresses the consequences of unregulated greenhouse gas emissions from economic and environmental standpoints and explains why the Copenhagen Accord will not sufficiently protect the world from the perils of climate change.

The Copenhagen Accord of 2009, which was ratified by the United Nations in an attempt to achieve the goal of the 1994 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, was designed to ensure minimal human effects on the Earth’s atmosphere by limiting greenhouse gas concentrations.

Nordhaus, however, argues that the Copenhagen Accord has been entirely unsuccessful due to cost and finance conflicts between developed and developing nations: First World countries do not want to pay for sustainability in poorer countries, while those developing countries do not want to pay for the pollution previously emitted by their developed counterparts.

Additionally, the Copenhagen Accord, while noble in its goals, requires no action by any party. Nordhaus consequently claims that the goal of the conference, a two degree temperature decrease in the next two hundred years, is unrealistic. Since predictions of future disasters are not effective in spurring countries to action, he suggests a global economic incentive to meet the goals and standards outlined at Copenhagen.

In an attempt to explain the severe economic impacts of uncontrolled climate change, Nordhaus uses economic growth theories. His main argument is based on the Ramsey Model, a classical economic growth model that promotes reducing consumption now in order to increase consumption later. Nordhaus applies this model to an environmental arena, as he explains, “Emissions reductions lower consumption today but, by preventing economically harmful climate change, increase consumption possibilities in the future.”

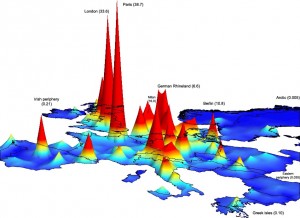

Nordhaus also examines five potential policy approaches and their economic and climate trajectories. These scenarios are: no climate change policy, a policy created to maximize economic welfare, a policy created to minimize temperature increase over time, the policy suggested in the Copenhagen Accord, and the policy suggested by the Copenhagen Accord assuming no support from developing countries.

Using these scenarios, Nordhaus models the following projected values: carbon dioxide emissions, atmosphere concentrations of carbon dioxide, global temperature increase, total cost of compliance, and carbon prices over time.

Graphical representations of the aforementioned scenarios, along with tables showing costs of implementation, lead to several important conclusions. First, even if the regulations proposed in the Copenhagen Accord were followed precisely, the goal of keeping temperature change under two degrees will not be achieved, and alternate policies that would achieve this goal are incredibly costly.

In addition to the conflict between economic and environmental benefits, there are other problems with trying to appease both political and environmental actors, such as the uneven division of cost between developed and developing nations and the famous free-riding problem.

Amidst these implementation issues, Nordhaus’ findings clearly reveal the dangers of ignoring environmental problems and the policies devised to help resolve them. While the model does not provide a decisive, singular solution to climate change, it sends a clear warning to countries around the world: saving money now is futile – the world may not last long enough for use of it later.