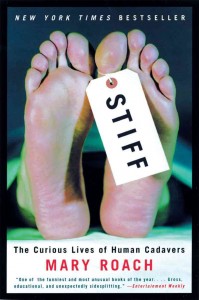

Mary Roach’s 2003 novel, Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, explores the varied and rich non-lives of our bodies post-mortem. Through frank, uncensored accounts of interviews of various people working with cadavers, Roach weaves a compelling and sometimes absurd tale of all the ways cadavers have become the unsung heroes of our history. Through a humorous and personal format, Stiff reads like an exploration of death and cadaver non-life rather than a scientific treatise on the use of cadavers in medical and non-medical fields. Roach explores the uses of donated (or non-donated) cadavers in all areas of life through the past and present, expanding beyond the expected medical field to cover pharmaceutical use, experiments in human composting, the study of human decay at a research institute in Tennessee, cadavers’ use as organic crash test dummies, and many other facets of post-mortem non-life.

This novel is especially relevant today because people are becoming less fixed in their own post-mortem plans, expanding beyond the customary burial or cremation to explore alternate routes of postmortem non-life, such as body donation and the eco-funeral, which basically composts one’s body. Indeed, the landscape of cadaver use has dramatically changed since the 19th century when only executed criminals could be legally used for medical research and grave snatching was an accepted reality in medical schools. Today, there is almost a surplus of donated bodies for scientific research because of more relaxed social and religious constraints regarding burial and post-mortem plans as well as a more sophisticated understanding of post-mortem decomposition and the scientific basis of life. Additionally, as people become more concerned with stresses that both burial and cremation put on the environment, many are searching for alternatives to these traditional methods.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers is a wonderful book that is extremely accessible despite its morbid subject. Roach writes the book through the perspective of a curious outsider exploring the world of cadaver research and post-mortem plans through a series of chapters, each containing a different story. Her prose is droll and her physical descriptions are frank and vivid, sometimes containing rather incongruous image comparisons — between a head and a roast chicken, for example. However, despite the novel’s engaging format, the knowledge contained within it is nothing groundbreaking and, upon completion of the book, amounts to trivia. The majority of these stories seem to focus on the grotesque extremes of cadaver use, often entertaining through shock value, such as when Roach researches the ultimately false rumor of a funeral home in Hong Kong selling body meat to a dumpling house in the area. This episode is not an outlier in terms of absurdity, but, interspersed with these shock value stories, Roach explores some of the most pressing concerns and newest developments in cadaver research and body disposal. She continuously details the sometimes obscure ethics associated with cadaver research and mountains of legal procedure necessary to start a project. She also demystifies the processes associated with cremation and burial and dedicates a chapter to new body disposal methods, focusing on Promessa, a Swedish company that commercialized the eco-funeral, and its body composting program.

Through these chapters, Roach begins to expand beyond a novel on post-mortem cadaver use and Stiff begins to become more of a treatise on death and our complex and sometimes sentimental relationship with the remains of our deceased. In the chapter “How to Know if You’re Dead,” Roach details the modern view of the basis of life as residing in the brain as well as ancient ones that delegated the human soul to the heart or liver. Here she details the “scientific search for the soul.” This chapter was truly the culmination of the philosophical journey of the novel, tying together the frank and grotesque imagery of the preceding and following chapters by integrating them into Roach’s final philosophy on the relations between the living and their dead. Roach seems to decry our sentimentality towards our cadavers and endorses the view that the person resides solely in the soul and that the body and soul are completely separate. By the end of the novel, Roach seems to have written a quasi-religious argument based upon science, history, and rationale about the status of the corpse after death.