For most diabetics, breakfast does not consist of a heaping bowl of sugar-heavy Cap’n Crunch. Instead, their initial fill comes in the form of an insulin injection. Luckily, scientists have recently discovered that a type of bariatric surgery known as gastric bypass may finally be the long sought-after silver bullet to the diabetes epidemic. As the number of individuals afflicted with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) continues to rise, this is a momentous finding for the field of endocrinology. While more research is necessary, gastric bypass surgery seems, at the present moment, a promising and long-term solution to curing diabetes without the need for hormones.

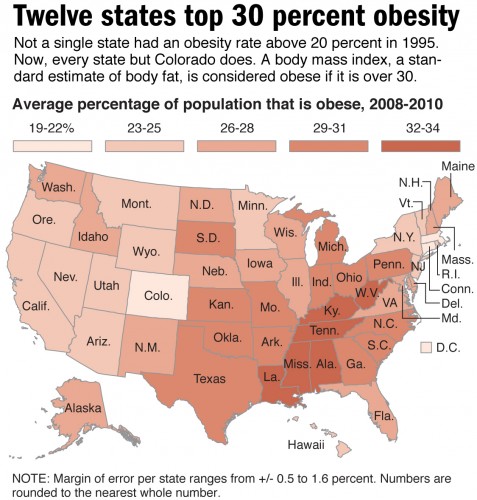

“It is clear that obesity and type 2 diabetes prevalences follow each other and that things are getting worse,” says Dr. Kitt Falk Petersen, one of Yale’s leading researchers in the Department of Medicine, Section of Endocrinology and Metabolism. “Now we also have this obesity epidemic in children in the U.S.”

Diabetes on the Rise

Globally, diabetes affects nearly 350 million people, increasing rates of stroke, kidney failure, blindness, amputation, and most importantly, mortality. In the United States alone, 25.8 million individuals are afflicted with the disease, and the government spends billions of dollars on research, treatment, and medical costs every year.

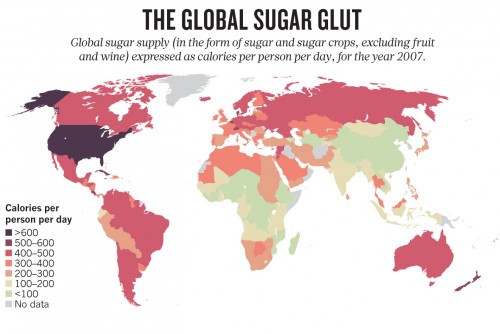

The link between obesity and T2DM is striking, especially in the U.S. T2DM, which was once known as “adult-onset diabetes” or “noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus” is now colloquially termed “diabesity.” With high-calorie food that is cheap, overabundant, and readily available to the typical U.S. family, the obesity epidemic is on the rise, and it has brought diabetes along a similar trajectory. In addition to being to being a physiological problem, diabetes is now being considered as a behavioral condition.

Surgery: A Novel Treatment Idea for Diabetes

Fortunately there is hope for individuals with T2DM. Two joint studies published last April in the New England Journal of Medicine reported a finding that came as a surprise to many endocrinologists. The team of scientists, led by Dr. Philip Schauer of Ohio’s Cleveland Clinic and Dr. Geltrude Mingrone at the Catholic University of Rome, showed in a controlled study that T2DM could be forced into remission with gastric bypass surgery. Studying a total of 200 obese diabetic patients, the researchers divided the patients into two randomized groups: those who received traditional hypoglycemic medication (insulin) and those who received bariatric surgery. The results were shocking: remission was seen in 42-75 percent of the patients in the gastric bypass surgery group, whereas 0-12 percent of patients exhibited normal glucose levels with medication.

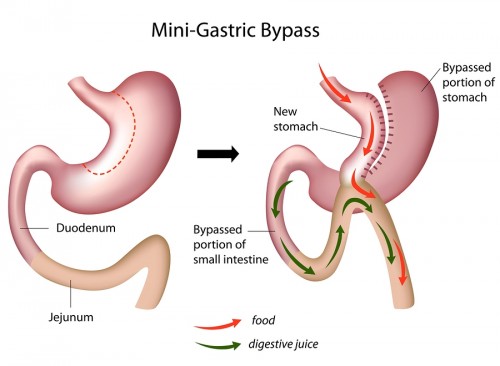

Interestingly, gastric bypass surgery has been used in the past as a common means of losing weight. In fact, nearly 200,000 bypass surgeries are performed in the U.S. per year: surgeons use camera-assisted, two-foot long poles, performing the surgery with five half-inch wide keyholes that make the procedure minimally invasive and bloodless. “Roux-en-Y,” the most commonly-practiced version of gastric bypass surgery, creates a small two-inch pouch in place of the stomach by rerouting the alimentary canal to further down the small intestine. Without surgery, food travels from the stomach through the duodenum, jejunum, and finally ends up in the ileum. After surgery, the small pouch is connected to the jejunum, while the rest of the stomach and the duodenum is bypassed and attached to further down the jejunum, creating a “Y”-shaped intersection. The large part of the stomach, while no longer used as a cavity for food, still produces useful gastric juices, which are now connected to the jejunum to drain. Undigested food now travels to the middle part of the small intestine and is digested in the last stretch of the intestine where it meets the gastric juices.

For obese patients, this “replumbing” of the gastrointestinal tract makes less of the intestine available to absorb nutrients. Gastric bypass also causes patients to reduce their food intake by virtue of the newly-crafted smaller stomach, causing patients to shed weight within weeks after the surgery. This is due to stretch receptors in the stomach that send messages to the brain, signifying that the patient is “full”. With a smaller stomach, patients become “full” more quickly. Although gastric bypass provides a scientifically-grounded method for treating obesity, its role in addressing diabetes is still uncertain.

What scientists are beginning to see is that rerouting the gastrointestinal tract also “reroutes” the chemistry of the body in a way that is not currently understood. “There may be different mechanisms at play in the short term after gastric bypass, such as potential hormonal effects,” says Dr. Petersen. So far, researchers have proposed two main hypotheses to explain how the common surgical procedure alleviates T2DM.

Some experts suggest that gastric bypass surgery causes a rebound in the level of incretins, which are hormones that spur insulin production during meals. Many T2DM patients do not produce enough incretin, so an increase in this hormone can quickly boost insulin production in their bodies. Yet, it is difficult to pinpoint specific hormones: there are over 200 in the gastrointestinal tract alone, many of which may play a role in reversing diabetes. Since rerouting the gut may influence a vast number of hormones other than incretin, understanding the curative properties of bypass surgery can be quite challenging; thus, the more conservative camp of researchers is hesitant to instantly hail gastric bypass as “the cure.”

An alternative hypothesis is that the passage of digested food into the duodenum triggers insulin resistance, as proposed by Dr. Francesco Rubino, an author on one of the two studies published in April. Rubino performed experiments on diabetic rats in order to find the relationship between the stomach and the duodenum in diabetes. He managed to sew an impenetrable flexible sleeve at the point where the stomach and the small intestine intersect in order to block contact between food and the duodenum. When fed a sugary diet, the rats with this silicone sleeve digested the food with no spike in blood sugar, showing the duodenum’s role in T2DM.

While the leaders of the two gastric bypass studies are hesitant to deem this a diabetes panacea, others are going as far as to call the surgery curative. “I was stunned. I had never seen such a magnitude of effect”, says prominent endocrinologist Blandine Laferrére in response to the surgery’s effects. However, since a remission merely indicates stabilized blood sugar levels, which are still prone to fluctuation some researchers in the field deem gastric bypass a “lifetime remission,” but not a cure.

Future Outlook

Questions about the applicability of gastric bypass are still in question. It is unknown whether all obese patients can receive the surgery, since obesity includes a range of BMIs, body types, and inevitably, different hormonal imbalances. Right now, there is no predictive marker of success with gastric bypass, or even how long remission could last. “It is important to note that far from all gastric bypass patients become normal weight or are able to keep the weight down long-term,” says Dr. Petersen. “In my view [long-term weight loss] can only be attained by keeping a diet for the rest of one’s life, which may not be the case for most people who have undergone gastric bypass.”

These limitations, in addition to the fact that patients may be reluctant to get surgery due to potential failure or a lack of health insurance, makes surgery a problematic cure. Thus, the researchers in the Schauer and Mingrone groups hope to create a drug that rewires the body’s chemistry in the same way that surgery does, in an effort to prevent remission.

Overall, gastric bypass surgery is able to do what current treatments have been unable to do: put obese T2DM patients into remission. As surgeons join physicians in the fight against diabetes, gastric bypass may soon be promoted to a first-line treatment in the arsenal that we have for treating diabetes. Eventually, researchers also hope to produce drugs that mimic the chemical effects of gastric bypass surgery, without the need for an actual operation. With more research, perhaps the future of treating T2DM patients will be over-the-counter, and not under-the-knife.

About the Author: Blake Smith is a freshman in Jonathan Edwards College intending to major in Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry. He is a writer for the Yale Scientific Magazine and works in Professor Joseph Contessa’s lab studying the role of glycosylation in the expression and regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Professor Petersen for her time and willingness to explain her research in an entertaining and intelligible manner.