Carol Orlando was 65 when her family members noticed the first changes. Her social graces began giving way to a detached brusqueness; her eclectic interests, to grinding repetition. Gradually, she lost the ability to care for herself, and her family assumed roles as her caregivers: washing and feeding her, and ultimately assisting with all aspects of her life. Frontotemporal dementia, an ailment of old age, was taking its toll.

As she descended deeper and deeper into this malaise, her speech devolved: “your dad taking dog for walk,” her daughter Wendy DeLucca recalled her mother casually stating, entirely unaware of the missing words. Then, seemingly overnight, Carol — known to be a caring mother with endless love to spread and often too much to say — suddenly stopped talking.

Of course, not everyone progresses like Carol. She is just one example, the tip of the iceberg. Aging occurs on a broad spectrum and can unfold with a variety of symptoms and other age-related complications, such as cancer or cardiovascular disease. Even without these diseases, aging in itself can be a taxing process: the vigor of youth fades away to be replaced by a slower pace of life, sore joints, deteriorating vision, and the accompanying loss of touch with the prevailing culture.

And while these natural changes may be pressing enough, the mental inertia of dementia — or the wear and tear of other age-associated diseases — exponentially compounds these challenges and exacerbates the difficulty of the journey for the elderly. Insidiously, these complications envelop individuals in a state of spiraling impairment, as DeLucca can testify to, gradually snuffing out their very essence.

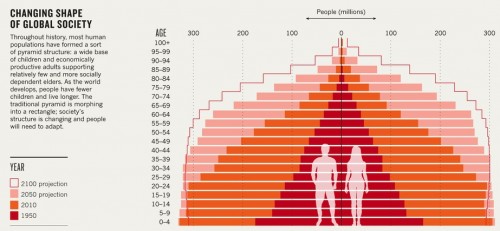

Unfortunately, these ailments are not rare. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 80 percent of older adults have at least one chronic condition and 50 percent have two or more. With the population on the rise and a rapidly growing elderly demographic, the situation is especially dire: estimates from the CDC project that the U.S. elderly population will double to 7.1 million by 2030, accounting for one out of every five Americans. Ironically, the increased life expectancy that has resulted from improvements in public health now poses a looming challenge: providing care for a graying population.

So what can we do? For decades, researchers have vigorously pursued avenues for the treatment and prevention of age-related diseases, yet solutions are still elusive. Recent investigations run the gamut, from studies of neuronal function and genome sequencing of centenarians to examining the relationship between diet and aging. “If we could find cures [for Alzheimer’s and other aging-related diseases], it would solve all of these problems,” Maria Tomasetti, South Central Regional Director of the Alzheimer’s Association, explains, “so everyone is searching for them feverishly.”

Though medical answers may be far in the future, public health research on aging is concurrently progressing. This work is carving out solutions to address arguably more immediate and equally important concerns of improving quality of life for the elderly, especially while the biological mechanisms of disease are still being unveiled. Recent research in this field points to gaps in our treatment of the elderly and of age-related illnesses and challenges the very underpinnings of how we perceive aging.

Seeing the Forest Among the Trees

It is clear that aging and its associated diseases impact the elderly, and thus public health has naturally focused on treating patient conditions. But Joan Monin, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health, argues that there is a missing factor in the equation. Behind every elderly individual facing health complications is at least one other person taking them to their appointments, assisting with household chores, aiding them through the difficulties: the caregivers.

Informal caregivers — those who are unpaid and who are often spouses or children — deliver 80-90 percent of personal and medical care to the elderly with chronic illnesses. Approximately 22.4 million Americans, or one in four, are informal caregivers, and the numbers will only rise as the baby boomers age. The signs of greater demand are already evident: Tomasetti notes that the number of calls to the 24/7 caregiver helpline offered by the Alzheimer’s Association has dramatically increased in past years.

The growing demand for caregivers also places significant strain on the economy and on our health care system. Recent Gallup statistics estimate that caregiving results in $25.2 billion in lost productivity, and a wealth of studies demonstrate that caregiving leads to negative outcomes in both health and mortality. In social psychology, such a phenomenon can be explained by the notion of cognitive empathy: people identify with the negative emotions around them, which leads to a state of shared suffering or, as Professor Monin describes, “literal vicarious feelings.”

As her disease progressed, Carol began to wake up in the middle of the night and rummage around her home, unable to be calmed. Situations such as these, along with routine care and distress, accumulated to a point at which it became difficult for the caregivers to take care of themselves. Her husband Richard, who once generally embodied a “stoic Sicilian” persona, became eager to vent his stresses and frustrations. And times were no easier for DeLucca, who felt like she was wearing a veil every day. Although sometimes it was “thin and gossamer,” it could instantly become “thick and suffocating.”

But Professor Monin believes that the hardships of caregiving can be greatly reduced. “Everyone suffers though certainly not to the same extent,” she said. So what is the key to regulating the extent of suffering? It all boils down to perspective, Monin proposed — specifically aspects, such as resilience and mutual understanding, that can be shaped by healthcare interventions.

In one of her recent studies, Professor Monin investigated caregiver response to spousal suffering and quantitatively found a positive correlation. By bringing both parties into the lab and recording the patient walking and carrying a 10-pound bag for three minutes, she demonstrated that cardiovascular arousal of caregivers significantly increased when watching their spouses performing the task, compared to watching another elderly person. With this “watered-down version of everyday life,” as Monin characterized her experiment, she concluded that caregivers overestimate the perceived suffering of their spouses. In turn, this predicts greater depression and stress for caregivers.

But what does this mean for the aging patient? Professor Monin explains that caregiver health and behavior have serious health implications for the elderly with chronic disease. In another one of her studies involving both the patient and the caregiver, Monin and her team found that deteriorating trust in the relationship, measured by attachment theory measures, exacerbates the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. “It is really important to help caregivers regulate their emotions in suffering,” she said. “We can then evaluate the state of a relationship and help prescribe personalized treatments.”

Caregiver health has been studied extensively in the past, but what is truly innovative about Professor Monin’s work is her focus on the caregiver-patient relationship, evaluating both parties in her studies and considering the relationship dynamics in solutions and treatments for age-related diseases. “Interventions to date have not been successful maybe because they do not involve both people,” Monin, who has a background in relationship studies, suggested. “Interventions need to be dyadic.”

Both Tomasetti and DeLucca agree. Tomasetti stresses that caregivers wrestle with the process alone because they are not aware of available resources. To better disseminate information, she is working with the Alzheimer’s Association on various projects, including co-opting physicians to provide caregiver treatment. “The reality is that caregiving is bigger than any one person,” Tomasetti, who is also an informal caregiver for her parents, said. And DeLucca shares these sentiments. “There needs to be a better pipeline of information for caregivers: through the primary care physician, through a care manager,” she suggested.

Professor Monin not only has clear support for her studies, but her work as a pioneer in this emerging field also speaks to a deeper issue: the tendency to single out aging rather than recognizing it within its context. She emphasized the “need to see the forest among the trees,” or in other words, the need to recognize that aging is not only about those directly suffering from medical conditions. Caregivers are essential parts of this greater context and serve important roles in the illness ecosystem.

Shaping Beliefs

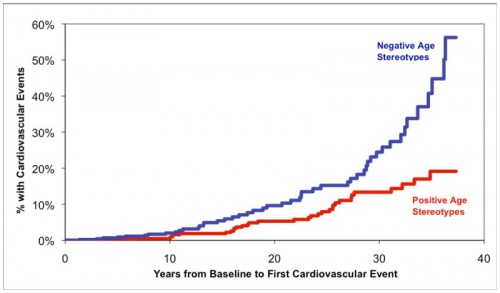

Becca Levy, Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Psychology and Director of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Division at the Yale School of Public Health, is another voice in the call for a shift in thinking toward aging. Specifically, Professor Levy studies the impact of elderly stereotypes on health outcomes. As a graduate student, she received a grant to study in Japan and was struck by the stark cultural contrast of elderly treatment there compared to in the United States. It is well-known that the Japanese boast the longest average lifespans, and Levy could not help but wonder if there was a connection between the Japanese value of honoring the elderly and longevity. Since this cultural exchange, she has made many cutting-edge discoveries about the detrimental impact of negative aging stereotypes, including adverse outcomes in cardiovascular health events, memory tasks, and recovery from disability.

While aging does consist of a combination of biological factors, Professor Levy explains that the common understanding of aging is partly a social construct and that we have created a “subjective onset of old age.” Stereotypes about age permeate throughout society and can be seen in what she deems somewhat arbitrary places, such as senior admissions fares or enrollment in Social Security. With these structures in place, the internalization of aging stereotypes starts at youth when people are not threatened by and thus most vulnerable to accepting and propagating them. Alarmingly, these beliefs are subliminally acquired, as Levy has demonstrated in studies involving unconscious word priming and its effect on task performance. Whether we are young or old, and whether we believe it or not, we are contributing to the aging process.

DeLucca, who despite her hardships expresses compassion towards aging and illness, has witnessed manifestations of negative stereotypes in acquaintances and relatives. Some children are embarrassed by their graying parents and end up “belittling and degrading them.” Though she sympathizes with the idea that children may one day have to care for their parents, she acknowledges that some others do not feel this way. In fact, DeLucca admits that many, perhaps unwittingly, approach aging with little understanding and patience.

Recent policy debates can also help to explain the extensive nature of these stereotypes. In the midst of the economic crisis, funding debates have fueled what Professor Levy calls “intergenerational tension,” pitting areas such as youth education and elderly care against one another in what she believes is a “false dichotomy.” Inevitably, financial troubles will lead to hard decisions being made, but framing them in this manner may be evidence of the elusive stereotypes at play. In addition, Levy’s studies have demonstrated relationships between TV and social media exposure, to negative aging stereotypes and health outcomes as these media outlets readily disparage aging and rarely highlight empowered elderly figures. Images portraying the elderly fumbling around, for example, may proffer a good laugh today but become damaging to our health once we inevitably age. In a way, we are promoting self-fulfilling prophecies as the negative stereotypes evolve in self-perception.

The steps to adjust stereotypes may seem ambiguous, but Professor Levy’s findings are already paving the way for practical solutions on an international scale. For example, the United Nations is currently working to strengthen human rights for the elderly, which will impact policy on a global level to reduce negative applications. Several European countries are also beginning to consider aging in government-level initiatives. And domestically, the U.S. government is currently reviewing “ageism” policies, especially concerning images in the media and marketing.

Graying with Glory

At an arguably opportune time, these studies may be pointing to the beginning of reconsiderations in how we think about aging. Robert Butler, the founder of the National Institutes on Aging, echoes these ideas in his book, The Longevity Revolution. Rather than thinking of the growing graying population as a burden, he suggests that we look at them as an opportunity and take advantage of what they can offer. In a similar vein, Nortin Handler begins his recent book, aptly titled Rethinking Aging by saying that “aging, dying, and death are not diseases.”

These scholars assert that we need to look at aging as not necessarily negative. Centuries of erosion carved out the Grand Canyon, and the aging of fermented grapes produces the most treasured wines. Riches of similar value lie within the world’s graying population — we just need to be open to finding this silver lining.

Ultimately, how we act and think now can have a very direct impact on how we live in the future. Aging and its associated diseases are far from solely being problems of the elderly. We will all grapple with these natural processes in some form or another: aging is everyone’s business.

After four years of being mute and eventually moving to a nursing home, Carol passed away on October 24, 2012. It was undeniably a trying time for her family, but DeLucca chooses to remember her mother for everything she was, to honor her, to share her story. In the spirit of redefining aging, DeLucca started a blog documenting her journey with her mother’s illness and writes in her final post not of the disease, but of her mother as a “selfless and caring” woman, “an avid bowler,” and an aficionado of dance and music. She was a chemist, a teacher, “a survivor.”

About the Author: William Zhang is a senior Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology major in Ezra Stiles College. He is interested in aging and neurodegenerative disease.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Professor Joan Monin and Becca Levy, Maria Tomasetti, and Wendy DeLucca for sharing their stories, expertise, and insights on aging.