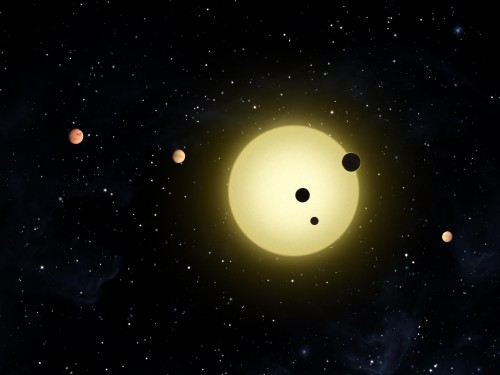

In January, researchers with Planet Hunters confirmed with 99.9 percent confidence the discovery of a Jupiter-sized planet called PH2b orbiting within the “habitable zone” of its star, the range where earth-like planets could have liquid water and possibly sustain life. The researchers also announced 42 new planet candidates, including 20 located in the habitable zone of their respective stars.

Planet Hunters is a collaborative project designed by Yale University and Zooniverse, an online collection of citizen science projects, that allows citizen scientists to search for exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – using data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Kepler space telescope public archives. Its “streamlined interface allows volunteers to look at a light curve in 5-10 seconds,” said Dr. Debra Fischer, a Yale Professor of Astronomy and co-founder of the project. Users examine the “light curves,” or star brightness levels, for possible planet transits, which are indicated by a dip in light curve brightness when a planet passes in front of the star.

“Many other events can also produce these signals,” said Dr. Ji Wang, a postdoctoral associate at Yale and lead author of the paper about the new discoveries. “Once we rule out all false positives, planets can be confirmed.”

“The planet PH2b itself cannot sustain life because it is a gas planet,” said Dr. Wang, “but this kind of gas giant usually has many satellites – take Jupiter and Saturn as examples. If the distance of the planet from its star is right, its satellite could be habitable. Finding a habitable planet is the first step; finding a habitable ‘exomoon’ is the next step.” However, detecting a so-called exomoon is extremely difficult because an exoplanet already has a very shallow transit signal, and an exomoon would have a signal at least an order of magnitude smaller.

The increased frequency of exoplanet discovery and confirmation means that “simply finding an exoplanet is kind of passé,” said Dr. Meg Schwamb, a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow at Yale working on Planet Hunters. Now, “we can move on to figuring out our solar system’s place in the galaxy,” by comparing other solar systems, such as that of PH2b, with our own.

PH2b, a gas giant, is roughly the same distance from its star as the earth, a small, rocky planet, is from the sun. “This comparison gives us an idea of different pathways of planet formation and frequency of life,” explained Dr. Schwamb. “We are getting to the point of comparative climatology and solar systems.”

These latest findings represent a success for both professional and citizen scientists working on Planet Hunters. “We present data in a way that’s accessible to everyone, and we try hard to show the public what we’re doing, and how we’re doing it,” said Dr. Schwamb. “We bridge the gap between scientists and non-scientists by bringing them in on the ground level. These discoveries highlight the power of eyeballs – we have 200,000 friends who can look through the data.”

The Kepler public archive releases data that scientists have already scrutinized, but Planet Hunters, using the same data, has almost doubled the number of gas giants found in the habitable zone. Professor Fischer explained that Kepler, which identifies exoplanets using the techniques of spectroscopy – light-curve analysis – and planet radial velocity analysis, is biased toward finding exoplanets that move faster, produce large light-curve signals, and transit more frequently. These planets are closer to their stars and thus less likely to be in the habitable zone.

Citizen scientists working on Planet Hunters, on the other hand, can consider transits on a case-by-case basis, and can visually detect planets which produce fewer dips in the light-curve; these are the planets with a wider orbit and a longer orbital period that Kepler algorithms often overlook. Nine of the recent planet candidates have orbital periods over 400 days, and most have periods longer than 100 days.

“I didn’t expect that volunteers would be able to find a significant number of planets that the Kepler computers couldn’t. Everything found by volunteers causes Kepler to improve their algorithms,” Professor Fischer added.

“We are entering this era of ‘big data’,” said Dr. Schwamb. “We need to find a way to go from gigabytes to terabytes. Machine learning will be much better with input from citizen science. It can ‘train’ an algorithm – this is where citizen science is going.”

“This is a fun, exciting question, and the public response has been incredible,” Dr. Schwamb added. “Seeing graphs on a screen doesn’t emotionally hit you the same way as images of galaxies do, yet people still come to Planet Hunters – this says something about how excited we are to find our place in the universe.”

Cover Image: An artist’s rendition of a sunset view from a rocky moon of the gas giant Planet PH2b. Illustration by H. Giguere, M. Giguere/Yale University. Image courtesy of Yale News and Debra Fischer.