It is often said that working together certainly has its merits; two heads are almost always better than one. But what about 250,000 heads?

Modern research is much more than simply admiring stars through a telescope or brewing concoctions in a lab. Data analysis, categorization, and pattern recognition are all integral parts of the scientific process. However, sometimes the manpower, or even computer power, of a single lab is just not enough to tackle an entire project, let alone complete it in an efficient manner.

As the value of including as many people as possible in various fields of scientific research has become increasingly recognized, crowdsourcing has come into play. Crowdsourcing utilizes the Internet as a platform for collaboration. Scientists can put their projects on the web, and anyone who wants to get involved can volunteer to perform simple tasks. Formally known as the citizen science movement, organizations have emerged around the globe within the last six years, creating websites that serve as headquarters for researchers to post their projects. Anyone can log on, choose a project of interest, and play an active role in the scientific process. The best part? There are no deadlines and absolutely no prerequisites.

Before becoming popularized via the Internet, the citizen science movement began with projects like the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count, which took place in December 2012 for the 113th time. Volunteers are asked to go into their backyards, count the birds they see over the course of 15 minutes, and send their results to the Audubon Society where conservation biologists analyze population trends.

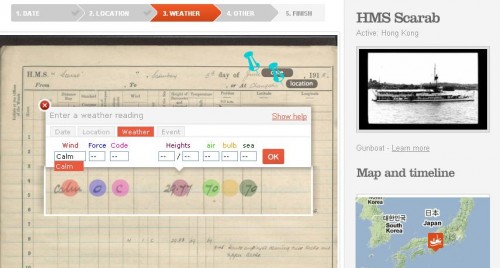

Since then, citizen science has evolved into programs spanning all disciplines of science. OldWeather, for instance, is a project where volunteers transcribe old weather records from nineteenth century ships in order for scientists to investigate climate trends. There are numerous astronomy projects such as PlanetHunters, where volunteers have successfully identified new exoplanets. Opportunities such as SnowTweets (mapping snow accumulation across the country), Project: Play with Your Dog (analyzing human-dog interaction through a cognitive science perspective), and even Bat Detective (listening to and classifying bat call recordings) can all be instantly accessed online.

Citizen science allows people to catch a glimpse of the realm of scientific research. The public is given a chance to discover what research entails and to share in the excitement of a world that does not usually receive much exposure — the “behind the scenes” part of science. Most citizen science projects have the appeal of a video game with the added value of making a meaningful contribution, letting users participate in scientific discovery while sitting on the couch in their pajamas.

The Citizen Science Alliance, a group of scientists, software developers, and educators who collectively operate these Internet-based projects, stresses the importance of the movement from a scientific perspective as well. There are overwhelming advantages to embracing the power of the Internet to include the public in research efforts. With the expansion of modern technology, data sets have multiplied in size, allowing researchers to work with more information than ever before. Computer programs have become exceptionally sophisticated to handle the data influx, but inherently human abilities, primarily pattern recognition and the uncanny ability to pinpoint irregularities, have yet to be perfected by any computer. Therefore, the human brain is an invaluable tool in the scientific process.

“It’s really a win-win situation,” commented Dr. Meg Urry, Yale professor and newly elected president of the American Astronomical Society. Urry is part of the team that operates GalaxyZoo, the first project launched on the Zooniverse, which is the homepage of the largest, most popular citizen science projects on the web today. Established by the Citizen Science Alliance, the Zooniverse attracts hundreds of thousands of people each day to log in, participate in projects, and even blog with the scientists about their experiences. The pioneer program, GalaxyZoo, garnered more attention than expected and skyrocketed the citizen science idea to success. Urry explained that the basic idea of the program is quite straightforward, appealing to those who have been “turned off by the tedium of rote learning before having the chance to do real research.” Users go on the site, take a short tutorial, and are asked to classify images of galaxies based on their shape. In its first six months Galaxy Zoo provided the same number of classifications as would a graduate student working around the clock for three and a half years.

“With computers you can enforce consistency…but GalaxyZoo compensates by having thousands of people participate,” said Urry. With thousands of people classifying one galaxy, scientists can compare answers to draw more accurate conclusions based on the majority consensus. Also, the individual performance of each user can be tracked. Site managers are able to analyze click speed and ratio of correct classifications, so any user found randomly clicking around will have their answers unweighted, again allowing for more accurate classifications.

Urry added that with GalaxyZoo, “consistency and bias could have been a big flaw, but this proves to be why it’s so valuable.” Although human bias and lack of experience with the material at hand may seem like pitfalls, there is a major upside to incorporating public opinion. People are able to call attention to irregularities that might go undetected in a computer program designed to strictly follow certain guidelines. In 2009 GalaxyZoo participants made a breakthrough discovery of a brand new class of galaxies by noting that it was not characteristic of the pre-set types — something a computer would never have been able to do. Using the findings, computer programs can later be improved to pick up on irregularities, improving technology in the long run.

Some critics argue that citizen science is not actually real science at all but rather a way for researchers to have other people perform tedious or unpleasant work. While it is true that all projects are based on forms of pattern recognition or data collection, the fundamental principle of citizen science is that the projects are a volunteer effort. Amateurs are an important part of science because they bring a fresh view and enthusiasm to the field. Furthermore, although participants are not certified scientists, their contributions remain an integral part of the scientific process; these seemingly menial tasks are crucial to each project and add to the overall understanding of the topic at hand. By providing a chance for people to experience scientific investigation, citizen science opens doors for those who might have never received the chance to be involved with science.

The growing movement is truly an instance of science adapting to modern society. Crowdsourcing brings accessibility and interactivity, transforming the face of science for both the public and the professionals who reap the benefits. Moreover, citizen science continues to gain momentum as there seems to be an endless supply of new scientific research along with plenty of people eager to make their own contributions. Two heads may be better than one, but 250,000 heads? Now that’s a game changer.