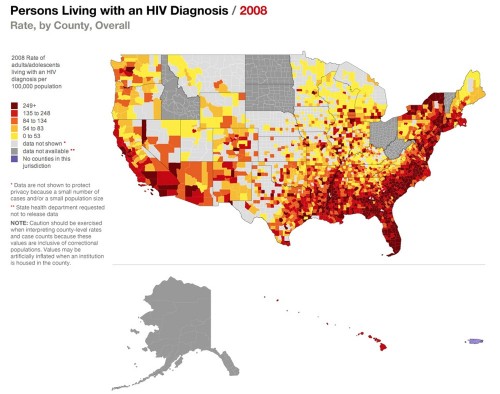

Imagine that HIV rates in crowded cities could be reduced with a single public health program. Imagine that this program could make both its users and police safer. Imagine that this program is incredibly simple and cheap.

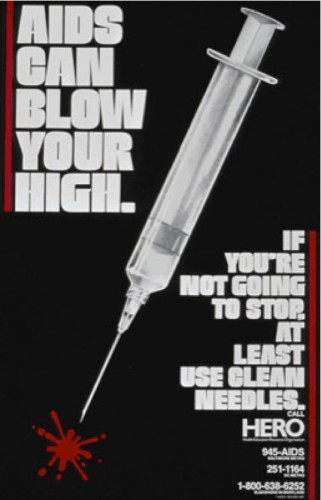

Now realize this: such programs exist, yet they are so controversial that few American cities reap their benefits and our national government refuses to fund them. Upon hearing their names without knowing the facts behind them, it isn’t hard to imagine why. They are syringe exchange programs, which provide clean needles to drug users at no cost.

HIV/AIDS and Injection Drugs

In cities, contaminated drug syringe use is one of the most common mechanisms of HIV transmission, causing 30 percent of HIV infections outside Sub-Saharan Africa. Whenever an addict injects heroin or cocaine, the syringe always retains trace amounts of blood. While these droplets are miniscule, they contain millions of HIV particles, easily enough to infect anyone else who uses the syringe again. When faced with withdrawal and a shortage of syringes, drug addicts often feel trapped and are forced to use dirty syringes.

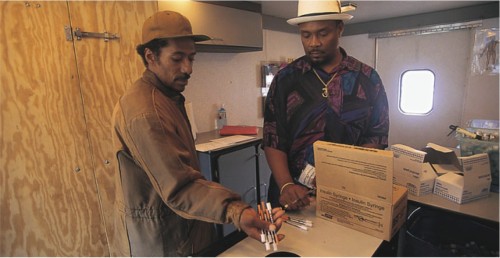

This problem has become the focus of research for many public health professionals, including Yale Professor of Epidemiology Kaveh Khoshnood. Khoshnood became interested in syringe-transmitted HIV as a graduate student in New Haven. For his Master’s thesis, he conducted a small-scale study on New Haven drug users, their barriers to treatment, and their utilization of New Haven’s syringe exchange program.

As a professor, Khoshnood wanted to continue this research and to demonstrate that syringe exchange programs were powerful tools in slowing the spread of HIV. In a five-year study, he and his colleagues recruited close to 1,000 drug users in New Haven; Hartford; and Springfield, Massachusetts. While New Haven and Hartford have syringe exchange programs and allow syringes to be sold over-the-counter in pharmacies, Springfield does not.

“We wanted to learn the ‘natural history’ of syringes in these cities, so to speak,” said Professor Khoshnood, including “where they come from, how they are used and discarded, what are the various influences on this natural history, where disease risks are introduced.” By tracing syringes and surveying drug users, the researchers found that in Springfield, syringes were used over and over again by many different people much more often than in New Haven or Hartford. Springfield also had a higher rate of HIV in drug users than the two other cities did. The syringe exchange programs were working.

Recruiting and obtaining meaningful survey responses from all 1,000 drug users was not an easy task. “Drug users have been shunned and stigmatized by society and are distrustful of any authorities that try to approach them,” said Professor Khoshnood. “It took a long time to establish trust with drug users, but they learned that our intentions were not to harm them. My prior experience with research on drug users was useful in this respect.”

Drug users are wary of authorities for good reason. Many are known to police, which makes them prone to pat-downs when walking the streets. The fear of being arrested reduces clean syringe use, even when syringe exchange programs are available — being caught with syringes, even clean ones, can serve as evidence of illegal drug use. Many addicts thus choose to avoid carrying clean syringes and take risks with used syringes later when they cannot quickly obtain clean ones. Thus, criminal issues carry over into public health, and Professor Khoshnood found that to address the health issues, he had to consider the criminal ones as well.

The Law v. Public Health

During his work on syringe exchange programs, Professor Khoshnood heard a lot more about the police than he expected to. “We realized that we needed to talk to the police, and somehow coordinate what we are trying to do with what they are trying to do,” said Khoshnood. “The police have a duty to enforce the law, and we are trying to improve public health, but these two approaches are not necessarily harmonized.”

Professor Khoshnood and his colleagues talked to various police departments about the reduced efficacy of syringe exchange programs due to drug users’ fear of being arrested if they carried syringes on them. The researchers had varying levels of success, depending on the police chief. For instance, in Springfield the police officers were “completely uninterested and had no flexibility at all. They even threatened to arrest us.”

In New Haven, however, police officers gave the researchers flexibility and allowed them to conduct their studies and distribute clean syringes with “their blessings.” Professor Khoshnood and his colleagues were even invited to do some training with the New Haven police. “They are sympathetic to our cause to some extent, but there’s a limit to their flexibility,” said Khoshnood. “If they catch a drug user, it is their duty to arrest them. Nevertheless, trainings and dialogues are very important.”

Training sessions with police served to show police the benefits of syringe exchange programs to themselves. For instance, one of a police officer’s greatest fears is being stuck by a contaminated syringe while patting someone down. Because these programs reduce the risk that those syringes are contaminated, officers were sympathetic to the idea.

From Papers to Policy

The ultimate goal of any epidemiologist, according to Professor Khoshnood, is having his or her research translated into policy change. Unfortunately, research usually does not get translated into policy, and when it does, it takes a very long time to have an effect. “We’ve had success from time to time,” said Khoshnood. “For the past 20 years, there was a ban on allowing government funds to be used for syringe exchange programs, which the Obama administration finally repealed in 2009. Research from our group and others was used to provide overwhelming evidence that these programs reduce HIV rates but do not increase drug use.”

However, Professor Khoshnood emphasizes that this change was “by no means a happy ending.” It took 20 years for this ban to be lifted, and now that it’s finally gone, syringe exchange programs still do not receive government funding because Congress has not allowed funds to be allocated.

Administration and government also slow down the public health research process itself. According to Professor Khoshnood, the most difficult part of his research is the amount of bureaucracy involved. “From developing, to conducting, to implementing, there is a lot of administrative red tape to slow down public health research,” said Khoshnood. “Often it is quite difficult to do highly innovative research. Most senior colleagues say you have to keep it simple in a research proposal — you can’t get too creative, or else you won’t get funded.”

Yet Professor Khoshnood makes clear that creative thought still definitely has a place in the field of public health. Sources of funding other than government grants, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, are often willing to support research that is less mainstream. And one of the most common sources of new creative ideas, in Khoshnood’s experience, is students.

“I love having students involved, having fresh ideas and asking a lot of questions,” he stated. “Every once in a while new ideas come up that we wouldn’t think to bring up among our peers, and these questions can bring new insights to the field.”

Looking Forward

As the results of studies such as Professor Khoshnood’s become increasingly well-known and publicized, he hopes that as many people as possible will realize that syringe exchange programs drastically decrease HIV incidence rates without increasing drug use. If Congress finally does allow federal funds to be allocated, syringe exchange programs have the potential to become widespread in America, curbing HIV transmission and shrinking the 30 percent of HIV infections due to contaminated syringes. As the world becomes increasingly crowded, simple solutions to persistent problems such as syringe exchange programs will be key to maintaining healthy populations.

About the Author: Christina de Fontnouvelle is a freshman in Berkeley College and Layout Editor for the Yale Scientific Magazine. She works in Dr. Yongli Zhang’s lab characterizing the dynamics of proteins using optical tweezers.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Professor Khoshnood for his time and enthusiasm in sharing his research.