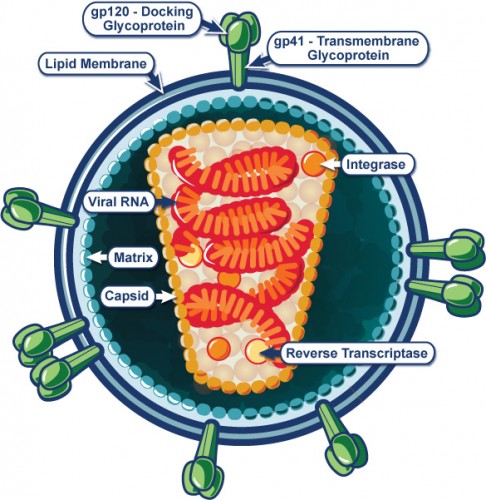

A study done in the lab of Howard Ochman, a former Yale Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology starting this year at the University of Texas at Austin, shows that chimpanzees infected with SIV lose the immune capability to maintain stable gut microbial composition. SIVcpz, the chimpanzee simian immunodeficiency virus, is closely related to HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus, and is the direct ancestor virus to the latter. Although many forms of SIV are non-lethal, SIVcpz can cause AIDS which, as in humans, depletes host CD4+ T cells. These cells play a role in regulating the growth of bacteria in the gut. One of the hallmarks of AIDS is the opportunistic growth of bacteria, unimpeded by the immune system.

In order to further investigate the connection between SIV infection and the gut microbiome, the researchers looked at the composition of gut microbiomes in chimpanzees pre-SIV infection and post-infection. The fecal samples which were analyzed were collected between 2001 and 2010 under Jane Goodall, a leading expert and pioneer in chimpanzee behavioral research. Lead author Andrew Moeller, a PhD student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale, sequenced the bacteria present in the fecal samples and was in charge of bioinformatic and statistical analysis.

Although the link between gastrointestinal dysfunction and HIV has been observed, insight into the phenomenon has been limited, in large part due to the significant variance between individual gut microbiome compositions. The importance of comparing individual microbiomes pre- and post-infection is therefore paramount. However, doing so in humans with HIV is impossible to track due to the unpredictability of transmission. Studying chimpanzees offers a solution to the problem.

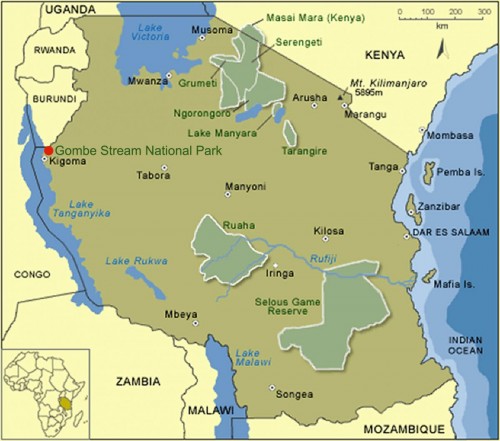

The chimpanzees in question live in Gombe National Park in Tanzania. “Chimpanzees in Gombe have been studied and sampled for decades, and they are naturally infected by SIV, the ancestor of HIV, so they represent the ideal system for revealing potential links between the gut microbiota and the progression of AIDS,” Moeller explained. The samples from six chimpanzees over a span of 9 years were used, all of which contracted SIV infection during collection.

From the six chimpanzees studied, a total of 49 fecal samples were analyzed. DNA from the samples was extracted, purified, amplified, and sequenced. Bray-Curtis dissimilarities (indicating compositional differences) and Euclidean and UniFrac distances (indicating phylogenetic relatedness) were calculated for 7000 randomly sampled sequences per sample.

The results show that SIV infection distorts the composition of the gut bacteria. After SIV infection, individuals had a much greater variance in the relative abundance of different types of bacteria. Additionally, results support the conclusion that this disruption of the bacterial composition of the gut is a result of long-term instability in the gut microbiome rather than a single shift at the point of infection. The longer the time since infection, the greater the changes in composition became. This was found by measuring the degree of change between consecutive samples taken before infection and after infection.

On top of these general changes found in the gut communities, the group also found that SIV infection led to an increase in the relative abundance of pathogenic bacterial genera, including Sarcina, Staphylococcus, and Selenomonas. They also found that Tetragenococcus, which was virtually absent in all of the samples before infection, had increased in relative abundance in half of the chimps after infection. Tetragenococcus is a genus of bacteria that promotes T cell immunity. However, although significant differences between composition and abundance exists on the level of bacterial genera, the study revealed stability in composition at the phylum level. Furthermore, no single group of bacteria was found to be associated with SIV.

How can these findings be applied to HIV and AIDS in humans? Moeller says that this research may open avenues for monitoring the lethal opportunistic bacterial infections that have a high chance of originating from the gut microbiome. “By monitoring gut microbiomes, it may be possible to identify rises in the abundances of potential pathogens … in the gut before the pathogens spread to the rest of the body and cause disease … allowing doctors to begin treatment for the infections early.”

The lab is continuing their investigation of the link between AIDS and gut community composition in a study in gorillas, which also contract a form of SIV closely related to HIV and also causes AIDS-like symptoms in its hosts.