Imagine you had a superpower that enabled you to read people’s minds.

Science has not yet advanced far enough to give anyone this ability, but functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) is probably the technology that comes closest. Over the past decade, use of fMRI in neuroscience and psychology research has greatly increased. While many features of fMRI have helped these fields progress, there have also been overly enthusiastic claims about fMRI’s credibility in explaining social science phenomena. There are strict limitations to what fMRI can confidently assert about people’s thoughts; over-reliance on fMRI scans has led to faulty research claims and public misconceptions about what this technology can really do.

First, it is important to understand how this technology works. The procedure uses magnetic fields and radio waves to form images of hemodynamic responses, or changes in blood flow. Whenever a particular brain area is active, it consumes oxygen, which requires increased blood flow to the region. Performing even the most mundane tasks, such as viewing a picture of a political candidate or solving a simple addition problem, causes specific areas of the brain to increase their oxygen consumption. fMRI maps these physiological changes and creates images of the areas with elevated blood flow. These maps can help researchers discern which areas of the brain are involved in completing certain tasks.

One of fMRI’s most celebrated advantages is its ability to quantify psychological processes that people are either unwilling or unable to report honestly. For example, people might not be aware that they respond emotionally to photos of loved ones, but fMRI can show emotion centers in the brain demanding higher blood flow. Another more controversial example is lie-detection. Deception activates the prefrontal cortex; with this knowledge, fMRI can be used to indicate whether or not an individual is lying. However, that does not that mean scientists can divine someone’s exact thoughts from what lights up in an fMRI brain scan. An increasing number of cautionary voices have started to emphasize the limitations of fMRI. These experts’ concerns range from queries on data collection methods to doubts surrounding the relationship between fMRI and neuronal activity. Some are cautious; others are cynical. Either way, scientists warn against overestimating the current abilities of fMRI.

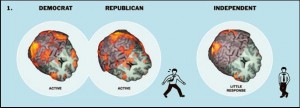

The problem with most fMRI psychology studies is that they are based on the premise that each cognitive task occurs due to the activation of a particular area in the brain. For example, the New York Times article “This Is Your Brain on Politics” explores the brains of voters from the 2008 election. The study claimed to predict the political ideology and party affiliation of potential voters by simply tracking their brain activity under fMRI while they viewed pictures of the political candidates. The study’s claims were based on differences in amygdala activation, which were interpreted to indicate anxiety about a particular candidate.

However, critics argue that it is implausible to draw reliable conclusions from mapping brain regions to mental states. Given the complexity of the brain and the interconnectedness of neural networks, such a conclusion seems to be based on arbitrary dismissal of other possible explanations for these observations. Indeed, activation of the amygdala can reflect “anxiety” about a particular candidate, but amygdala activation can also be caused by arousal and positive emotions.

Some prominent neuroscientists have also questioned the validity of generalizations about individual brains that are based on averaged data. In a study by Harvard University professor David Cox, brain activation varied from one individual to the next. The study, which used a sample size of six, showed that different brains are activated in different areas upon seeing the same object. At larger sample sizes, such as those used in most fMRI studies, it becomes possible to calculate a grand average of the data and thus provide an “average” region of activation due to stimuli. Yet this average overrides the uniqueness and individuality of each brain and therefore should not be taken as a completely accurate representation of brain function.

These criticisms in fMRI’s applicability to mind-reading suggest that the field of fMRI has not yet arrived at the stage where we can confidently trust all of its results.