The past century has seen marked improvements in neuroscience. Scientists have discovered ways to observe electrical currents that carry information around the nervous system, employing techniques like electroencephalography and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Doctors can now carry out complex surgical operations to heal and restore the brain. Social scientists can model individual behaviors based on everyday psychological biases, such as the tendency to spread gossip.

However, none of these fields have come close to a complete definition of the mysterious concept of identity. Key questions remain unanswered: how do we create a sense of self? How do we identify and characterize people? Most importantly, how do we characterize reality? Psychologists argue about how identity develops, while neuroscientists dispute where identity manifests itself in the human brain.

The main theories of identity formation come from two psychologists, Erik Erikson and James Marcia. Erikson used patient therapy, dream analysis and puppet plays with children to develop his identity theory. Some psychologists questioned his methods and his credibility (the highest academic degree he earned was a high school diploma), but Erikson was successful nonetheless in creating a widely accepted theory for how identity develops in different life stages. Each stage is characterized by a relevant crisis, such as “trust versus mistrust” for a newborn, “competence versus inferiority” for a young child and “generativity versus stagnation” for middle-aged adults.

The most important stage for identity formation according to Erikson’s theory takes place from ages 12 to 18. The crisis in this time period is “identity versus role confusion.” Humans begin to ask, “Who am I?” Erikson postulates that earlier conflicts must be resolved to conquer this critical stage, termed the “identity crisis.” During this stage, Erikson claims humans should begin to feel a deep-seated sense of trust in others and a sense of independence and control over life. This adolescence stage is crucial for forming a well-defined life, or, at its worst, spiraling into a life of instability and confusion.

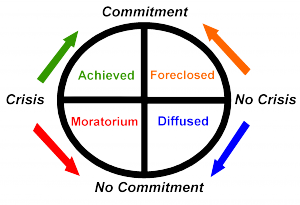

James Marcia, a Canadian neuropsychologist and professor, added to Erikson’s groundbreaking work in identity theory. Rather than adhering to Erikson’s dichotomy of identity and confusion, Marcia proposed that identity arises from the choices made about certain personal and social traits. To clarify this decision-making process, Marcia described two stages: crisis, in which previous life choices are re-examined, and commitment, the outcome of crisis.

Individuals with a well-developed identity, by Marcia’s theory, should have a good sense of their strengths and weaknesses and a secure sense of self. Of course, for many college students, it is possible that Marcia’s model does not hold much personal value. College students often reach the age of 20 before determining their majors, let alone their career paths; in contrast, Marcia’s model expects vocational decisions to be undertaken in adolescence. Similarly, most college students have not yet developed a complete sense of strength, weakness, and self when they enter college at the age of 18. People in this age group may thus face difficulty applying this model to their own lives.

In addition to the ongoing debate surrounding identity development, the cerebral location of an “identity region” also has yet to be resolved. Scientists agree that several areas of the brain work together to update the sense of identity, but many experts have focused on the cortical midline structures. This part of the brain is located near the center of the frontal lobe. It communicates extensively with the medial temporal lobes, which process memory and emotion.

In cases where the medial temporal lobes do not provide complete or correct information to the cortical midline structures, identity delusion can occur. For example, 23-year-old Adam Lepak of Syracuse, New York sustained massive brain injuries in a 2007 motorcycle accident. Now, he frequently thinks his mother is part of an alternate, fabricated universe, and he cannot maintain an up-to-date sense of who he is because of lesions in his brain’s emotion and memory centers. However, with extensive exercises, such as identifying people in mirrors and doing physical therapy, some of the brain functions Lepak lost are starting to reappear. His story not only shows the progress of neuroscience but also supports the theory that a combination of brain regions are implicated in identity formation and maintenance.

The development of a large and capable brain explains the intricate nature of human civilization today. However, when it comes down to the deepest question regarding the brain — “Who am I?” — scientists are confronted with an unsolved mystery. Researchers can explore identity formation through neuroscience and psychology, but this phenomenon ultimately remains an incomplete puzzle.