Loping through shallow waters with their duckbills agape, the hadrosaurs of popular imagery are no roaring, ancient conquistadors. They are round and gentle-looking, the sort of dinosaurs that, when cast as miniatures in plastic, one might give to a child. But according to the research of Yale University’s Matthew Davis, our herbivorous friends seem to have boasted at least one tough feature: their skin.

Davis’s research began with a curious paleontological fact: hadrosaurid skin was more prevalent in the fossil record than the skin of other genera. Why? Some scientists claimed that because hadrosaurs lived alongside rivers and often perished in flash floods, their remains—safely cached in sediment–were unusually likely to escape scavengers and the elements. A simpler explanation was that hadrosaurids left behind more skin because they were particularly widespread and numerous. Like New Haven’s squirrels, the hadrosaurs of this theory were abundant but not physically superior in any way.

Unsatisfied with both hypotheses, Davis searched 180 scientific reports on featherless dinosaur skin published between 1841 and 2010. He also analyzed the data of paleontologists Tyler Lyson and Nicholas Longrich, who had studied 80 hadrosaurids and 263 non-hadrosaurid specimens from a single region and time period.

His findings: Twenty-five percent of the hadrosaurs in the local study maintained skin, compared to only two non-hadrosaurid specimens. And in the global literature search, “hadrosaurids had more body fossil skin examples than any other clade both in total number [46 percent] and in examples per species.” This means that hadrosaur skin is not just the most common type of dinosaur skin in the fossil record; it is also the most likely to endure in a given fossil sample.

Davis cautioned that we do not yet know why hadrosaur skin lasts the best. “I don’t yet have any evidence to suggest that their skin was any thicker,” he told me. “Just stronger.” And what is meant by “stronger”? Further study is needed. Scientists in other labs are currently examining the best-preserved skin samples with electron scanning microscopy, measuring the thickness of individual layers of skin, and using electron microprobes to figure out the fossils’ elemental composition.

But while hadrosaurid skin samples have yet to divulge the secrets of their strength, they have at least illuminated other questions of anatomy. One fossil, whose skin traces suggest the form of a “webbed mitten” rather than “actual fingers”, supports the claim that at least some species of hadrosaurs “were almost certainly at least semi-aquatic.”

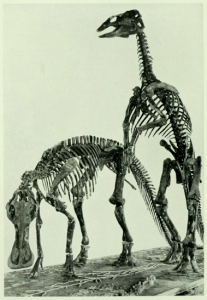

Other hadrosaurid specimens with skin have been used to create “fleshed out” computer models. These supplement the predictions that paleontologists can make by examining dinosaur bones for the divots of muscle attachment sites. For example, a specimen whose skin stretched from the tip of its tail to right above its knee has revealed that the species’ tail muscle connected to and supported its legs, likely making it strong enough “to outrun T-Rex or other predators”. Apparently, skin wasn’t the hadrosaur’s only tough feature after all.