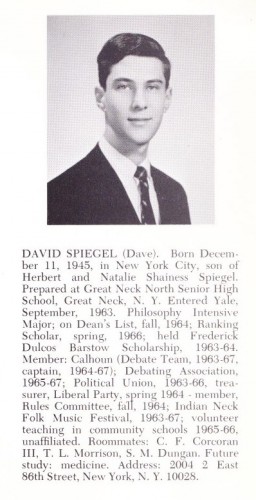

In The Fault in Our Stars, Hazel, a 16-year-old girl diagnosed with terminal cancer, falls in love with Gus, a philosophical 17-year-old boy she meets at a cancer support group. Had it not been for Dr. David Spiegel, a 1967 Yale graduate, Hazel and Gus would never have met. Among his plethora of projects, Spiegel, alongside his mentor, existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, started the first cancer support group in 1976. This psychosocial approach to cancer care was immensely successful, and it led to the ubiquity of cancer support groups we see today.

Spiegel is currently a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. His fascination with the brain can be traced back to his undergraduate years, when he fell in love with — and decided to major in — philosophy. “Philosophy helped me better think about how people are structured,” Spiegel said. Still, he knew he wanted to enter a field with the potential to create new knowledge. “Being a philosopher would be great — teaching freshmen Plato, not so much,” Spiegel added. Ultimately, his desire to gain a deeper understanding of human beings led him to the intersection of medicine and philosophy.

After completing medical school and residency at Harvard in 1974, Spiegel dove into the research of mind-body interactions at Stanford. In his first cancer support group, specifically for women with breast cancer, he observed the effects of group psychotherapy on cancer outcomes. “Existence is fleeting – we don’t appreciate what it is to exist until we contemplate the idea that we won’t,” Spiegel said. “We work with people who are facing that and see if it can be a period of growth.”

In the groups, Spiegel led discussions on detoxifying death, grieving over losses, and living with the knowledge that death is inevitable. The process is anything but easy: “It’s like looking into the Grand Canyon when you’re afraid of heights,” Spiegel said. But he added that “facing the worst” helps cancer patients gain strength. He soon noticed a pattern in the support group: at first, the women tried to guard their thoughts, but once they discovered that opening up made them feel better, they began to communicate more with each other and with their families. Being surrounded by a group of women with advanced cancer fostered a sense of community for each woman.

In 1989, Spiegel published the results of his groundbreaking study on support groups, which found that group psychotherapy extends the lives of cancer patients by an average of 1.5 years. Since then, his paper has been cited more than 2,600 times. In 2012, he was inducted into the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies for the significance and influence of his research. “We found that depression, social support, and sleep disruption all predict survival,” Spiegel said, summarizing his major findings.

Spiegel also specializes in research on hypnosis. One of his current projects uses fMRI to detect differences in the brain during high and low hypnotic activity. “It’s lots of fun — we put students in a scanner, then hypnotize them!” he said.

At Yale, Spiegel took Directed Studies, played guitar for Neck the Indian Folk Music Club, and was an active member of both the debate team and the Yale Political Union. His most difficult class was organic chemistry. He found the interaction between his courses in medicine and his courses in philosophy fascinating. “I kept wandering elsewhere and getting drawn back to human psychology,” Spiegel said.

Spiegel intends to continue his passionate pursuit of understanding how the mind affects the body. In addition, he would like to see techniques such as hypnosis taken more seriously. According to Spiegel, hypnosis is often portrayed as a “stupid stage show rather than a therapeutic tool.” He hopes to harness the massive reach of the Internet to disseminate tools that patients can use to deal with trauma.

When asked whether he has any advice for current Yale students hoping to follow in his footsteps, Spiegel replied: “Pose yourself a question, and acquire the education.” From seeking an interdisciplinary understanding of philosophy and medicine to spearheading a new forefront of psychotherapy, Spiegel exemplifies his own counsel.