Some 20 years ago, planets orbiting around other stars were thought to occur only once in a blue moon. Today, the existence of more than 1,000 of these extrasolar planets is confirmed, and two of the recently validated planets are the most Earth-like that scientists have ever detected.

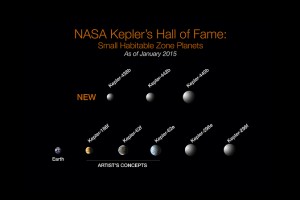

Scientists at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, led by Guillermo Torres, analyzed 12 extrasolar planet candidates from NASA’s Kepler telescope data. Using statistics and high-powered telescopes, the study validated the existence of 11 extrasolar planets, also called exoplanets. Of the eight new exoplanets, three reside in the habitable zone, a region in which planets are able to support liquid water. Two of the three, Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b, are similar to Earth in size and composition. Kepler-438b has an Earth Similarity Index of 0.88 out of 1.00, the highest an exoplanet has ever reached. Similarity to Earth may not be fascinating in itself, but this high Earth Similarity Index makes Kepler-438b a candidate in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Though the planets are not perfect Earth analogs, they are strikingly similar to our planet. However, the two Earth-like exoplanets both orbit stars smaller and less luminous than the Sun. Kepler-438b orbits around its star, a red dwarf, in 35 days and enjoys 40 percent more light than Earth as a result. Kepler-442b takes slightly longer — 112 days — to orbit its star, and receives about 30 percent less light than Earth. In terms of size, Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b are 12 and 30 percent larger than Earth, respectively.

The recently validated planets are part of a sprawling dataset of potential exoplanets. Like most of the other exoplanets observed by the Kepler telescope, they were identified when they transited in front of their star. During a planet’s transit, scientists can detect a slight dimming of the star’s brightness. However, the transit method can sometimes generate a false positive — an eclipsing star might be mistaken for a transiting planet. This possibility necessitates further validation tests.

Unfortunately, such tests are not easy to conduct on the new exoplanets. “The only downside of the amazing exoplanet detections from Kepler is that the stars and planets are hundreds of light years away, making it difficult to use other techniques and learn more about these intriguing worlds,” said Debra Fischer, Yale Professor of Astronomy and an exoplanet hunter.

The exoplanets’ distance from Earth, compounded by their small size, means that they cannot be validated through Doppler spectroscopy. Known informally as the wobble method, this technique takes advantage of the gravitational pull a planet exerts on its star. Though planets can be validated through other methods, the Harvard scientists lacked data typically gleaned from the wobble method about planet mass and composition.

In order to make these leaps, Torres and his team relied on statistical analyses of other confirmed exoplanets. An analysis of Kepler data by Harvard graduate student Courtney Dressing revealed all confirmed planets with radii less than 1.5 times that of the Earth are rocky, have iron cores, and are composed of similar proportions of an important component of Earth’s mantle, magnesium silicate.

The validation of these Earth-like exoplanets has exciting implications on the study of the origin of life on Earth, as well as on the search for extraterrestrial life. As the larger of the two new exoplanets is 1.34 times the mass of the Earth, the likelihood of it being terrestrial is very high.

“Astronomers are intent on finding analogs of our Earth because life emerged from the chemical processes on our planet. This suggests that worlds with similar composition, temperature, and pressure are more likely to have the chemical, geological and atmospheric processes that allow life to arise,” Fischer said. The validation of Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b represents a major step forward in the quest to find truly habitable worlds outside of Earth, and possibly even life as we know it.

Cover Image: An artist depicts an Earth-like exoplanet orbiting around a planetary nebula. Image courtesy of David A. Aguilar, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.