After completing treatment at a hospital, the last thing people want to do is return. Yet between June 2009 and June 2010, the national rate of 30-day readmission was an astonishing 58.2 percent. Doctors were puzzled by why patients were returning with the same or new problems. Many suspected that readmission rates were linked to the quality of care in hospitals.

In response, hospitals have pointed out that there are a number of factors beyond quality of care that might explain the high frequency of readmission. Many of these extraneous factors are not within hospital control. Patients of low socioeconomic status, for example, are more likely to fall victim to untreated diseases and unnecessary procedures. As a result, their chances of being readmitted are significantly greater.

So when a group of Yale scientists in 2008 chose to evaluate hospitals based solely on readmission rates, without adjusting for the socioeconomic status of patients, their decision drew outrage from many hospitals that treat large populations of the poor. The Yale physicians, led by Dr. Harlan M. Krumholz, maintain that their decision was in the best interest of patients, and recent studies support their claim.

As hazy as the data may be, these conflicting opinions make one point exceedingly clear: Hospital readmission is a complicated public health issue. Affecting positive change will likely require input from researchers, providers, and patients alike.

Straining safety net hospitals

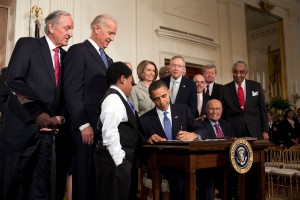

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010 established the Readmissions Reduction Program (RRP) with the mission of raising quality of care in hospitals while cutting costs. In order to assess the progress of this mission, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) collaborated with the Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation (CORE) at the Yale School of Medicine.

The duo created measures that compare the number of predicted readmissions to the number of expected readmissions at each hospital. The predicted number of readmissions is based on a hospital’s performance given its mix of medical cases. The expected number, on the other hand, is based on national performance at the level of that hospital’s case mix. This approach is analogous to comparing observed and expected readmissions. It allows a particular hospital’s performance to be compared to an average hospital’s performance with the same case mix.

The government imposes financial penalties on hospitals with higher than expected readmission rates. A total of 278 hospitals received the maximum penalty in 2012. Among the hospitals fined included Mount Sinai, NewYork-Presbyterian, and — ironically enough — Yale-New Haven Hospital.

The big names aside, many safety net hospitals were also fined. Core safety net providers are defined by two characteristics: First, they must maintain an open door policy, accepting patients regardless of their ability to pay and offering nonexclusive access to all health services. Second, a substantial number of their patients must be uninsured, on Medicaid, or otherwise financially vulnerable.

Spokespeople from some safety net hospitals argue that these institutions are being unfairly targeted by the RRP because the measures do not consider the socioeconomic status of their patients. Furthermore, they believe that the payment penalties will compromise their ability to care for disadvantaged populations.

A recent study by Dr. Salomeh Keyhani at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), however, found that the addition of social risk factors does not alter hospital readmission. The work, recently published in The Annals of Internal Medicine, sampled 5,000 veterans admitted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in 2007 with a diagnosis of stroke. Researchers then developed three readmission models. The first was similar to the one written by Yale researchers; the second considered social risk factors; and the third considered both social risk and clinical factors. Social risk factors included socioeconomic status, homelessness, and substance abuse. Clinical factors included disease severity, as well as the number of previous medical visits.

The UCSF study found that these social risk factors have a negligible effect on model performance. Furthermore, they determined that social risk factors have little effect on the relative ranking of hospitals. They concluded, therefore, that clinical rather than social risk factors are the most important predictors of 30-day stroke readmission rates.

Yale responds

Krumholz, who serves as director of CORE, thinks that the study coming out of UCSF was helpful. However, he believes that Keyhani’s findings do not preclude the possibility that adjustment for socioeconomic status could be important for particular institutions. Keyhani’s research does not resolve the debate, which Krumholz believes should be centered on the best interest of patients.

Krumholz asserted that patients’ interests have been his first priority from the very beginning. Before the Affordable Care Act, CORE had been working with CMS on process measures, which assess how health care professionals deliver services. “Increasingly, I was getting frustrated with these process measures. I was beginning to feel that what we needed to do was pivot, to start measuring outcomes,” Krumholz said, adding that he wanted to see the impact that quality of care has on patients.

The government asked CORE to measure one outcome in particular: cost. But to Krumholz, cost was a red herring. He was worried that it would be a difficult measure to interpret. For example, some people might equate higher cost with higher quality care. “[We wanted to] create new measures that might favorably affect peoples’ responsibility about cost, but really in the best interest of patients,” Krumholz said. He noticed that little was being done to actually reverse the rise in readmission rates.

Krumholz’s idea evolved into the 30- day readmission rate metric, now at the core of the RRP. In spite of some healthcare officials’ calls for modifying these measurements, Krumholz defends them for two reasons: “One, we’re not sure to what extent it’s quality of care or something beyond the control of the hospital. Two, we don’t think you should hide the differences. If you adjust in the models for the socioeconomic status of the patients, it will make those places appear as if they’re doing as well as everyone else.”

The risks of adjusting for socioeconomic status are also apparent in the evaluation and ranking of public schools. Say, for example, two schools are being compared based on test performance. Each is assigned a grade — A, B, or C — based on the ratio between expected and actual mean score. One is suburban, and the other is inner city. We expect that the suburban school will do better based on the higher relative wealth of its students’ families. These expectations are taken into account when calculating each school’s grade. Now, say each school performs as expected. At the end of the year, we give each an A. Great, right?

Not quite. If we were to rank schools across the country based on this methodology, we might find the inner city school in the upper quartile. The school would appear as if it had performed extremely well, perhaps even better than some schools that had numerically higher test scores. Adjusting for socioeconomic status would similarly conceal disparities among hospitals. We essentially trick ourselves into believing that everything is fine, when in fact it is not. And when we fall prey to such an illusion, we have no way of knowing where to funnel resources and capital.

Targeted reform

Krumholz points to recent findings that indicate that the RRP measures have sparked positive change. National and regional efforts to reduce readmission rates are already underway. The CMS supports programs like the Partnership for Patients, which provides $500 million in support of transitional care services. National 30-day readmission rates have fallen steadily from 58.2 percent in July 2009 to 50.1 percent in June 2013. “It would be hard to believe this would have happened had we not implemented the measures. [People] weren’t paying attention to it [before], and now they are,” Krumholz said.

Krumholz concedes that while he believes in the measures, he does not agree with all aspects of the payment policies. He asserts that the government should take into account whether or not a hospital serves disadvantaged populations before imposing fines. This would resolve the challenge of burdening safety net hospitals without concealing disparities. But whether or not the policy will be amended remains uncertain. Many incoming legislators do not seem too keen on the ACA, much less its provisions regarding readmissions.

All of this, according to Krumholz, is out of his hands for now. “That’s [up to] Congress and the government,” he said.

About the Author: Patrick Demkowicz is a freshman biomedical engineering major in Ezra Stiles College. He spends his time studying influenza in the lab of professor Akiko Iwasaki, building a radio telescope with the Yale Undergraduate Aerospace Association, and writing for the Yale Scientific.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Dr. Krumholz for his time and contributions.

Further Reading:

Keyhani, Salomeh, Laura J. Myers, Eric Cheng, Paul Hebert, Linda S. Williams, and Dawn M. Bravata. 2014. ‘Effect Of Clinical And Social Risk Factors On Hospital Profiling For Stroke Readmission’. Annals Of Internal Medicine 161 (11): 775. doi:10.7326/m14-0361.

Krumholz, Harlan M., and Susannah M. Bernheim. 2014. ‘Considering The Role Of Socioeconomic Status In Hospital Outcomes Measures’. Annals Of Internal Medicine 161 (11): 833. doi:10.7326/m14-2308.

Daughtridge, Giffin W., Traci Archibald, and Patrick H. Conway. 2014. ‘Quality Improvement Of Care Transitions And The Trend Of Composite Hospital Care’. JAMA 311 (10): 1013. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.509.

House, J., & Williams, D. R. (2000). “Understanding And Reducing Socioeconomic And Racial/Ethnic Disparities In Health.” In B. D. Smedley & Syme, S. L. (Ed.), Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social And Behavioral Research, (Pp. 81-124). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Fiscella, Kevin, Peter Franks, Marthe R. Gold, and Carolyn M. Clancy. 2000. ‘Inequality In Quality’.JAMA 283 (19): 2579. doi:10.1001/jama.283.19.2579.

Lewin, Marion Ein, and Stuart H Altman. 2000. America’s Health Care Safety Net. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine.

NPR.org,. 2012. ‘Thousands Of Hospitals Face Penalties For High Readmission Rates’. https://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/08/13/158711121/thousands-of-hospitals-face-penalties-for-high-readmission-rates.