A group of students listens intently as Yale professor Richard Lethin gives a lecture on computer architecture. His course, which covers the integration of software and hardware to produce computer systems, intrigues students — just as similar lectures fascinated Lethin during his undergraduate career at Yale.

By showing how far computer design has come — from simple computer architectures of the past to artificially intelligent systems of the present — Lethin inspires students to write the code for the next chapter of computer science. As the current president of Reservoir Labs, Lethin is helping to write the current chapter, by developing more efficient computer systems and improved cyber security technologies. His path from curious child to president of Reservoir Labs shows his ever-expanding passion for computer science, regardless of the role he plays — whether a student, an engineer, or a professor.

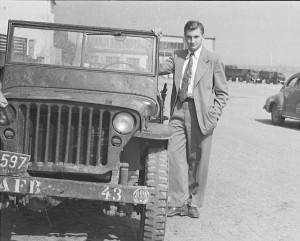

Long before Lethin was standing up at the front of a classroom, encouraging students to pursue computer engineering, he was motivated by his father’s work to study programming. His father — also a Yale engineering graduate — helped design the radar used in the Berlin airlifts, and often brought home early digital calculators that captivated Lethin as a child. “[His] was a very glamorous job, and, as a son, I admired him,” Lethin said. His fascination with engineering was only heightened by the Apollo space program. The exciting environment in which Lethin grew up, coupled with his early access to programming, fueled his interest in engineering and computer science.

Lethin’s early passion for engineering pushed him to study the subject at Yale. As an undergraduate, he not only dedicated himself to his studies but also to extracurricular pursuits. He joined a number of Yale’s music groups, and played the trombone in jazz band, concert band, and marching band. Reflecting on his classes, he recalls his political science and African art courses as fondly as his engineering ones. “I think Yale engineering students have a unique advantage in their access to a broad range of resources and courses,” Lethin said.

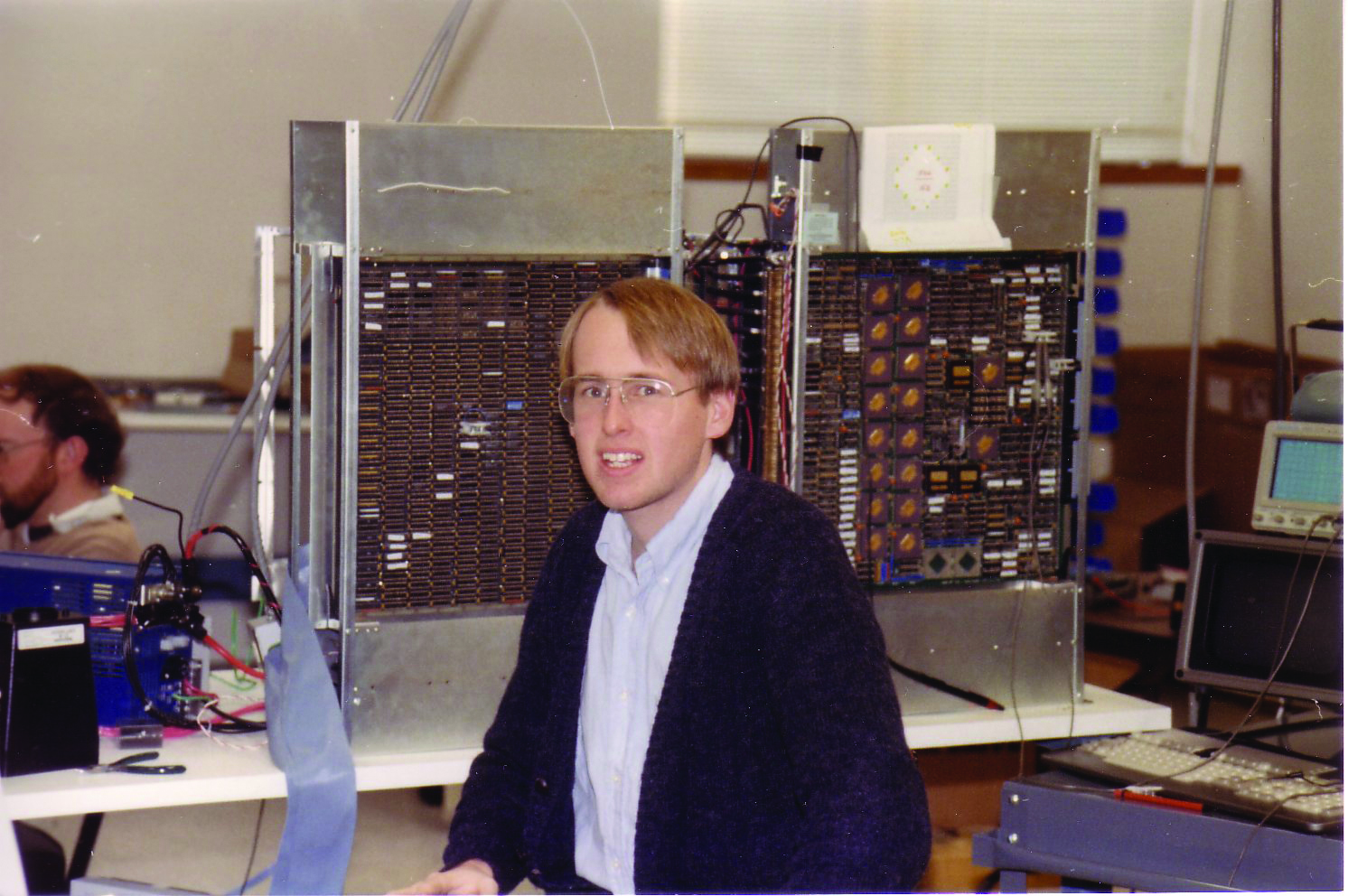

After four fulfilling years at Yale, Lethin — like many other engineers — took time to work in the field before attending graduate school. Between his time as a Yale undergraduate and his years in graduate school at MIT, Lethin worked at Multiflow Computer, a company founded by his computer architecture professor Josh Fisher. There, Lethin got involved in a variety of tasks, from working on computer circuitry and architecture to improving the efficiency of computer systems. “I learned a lot about what it takes to build something real, and that proved to be really useful in getting into graduate school,” he said.

Lethin added that his experience in research and development, when he investigated the best ways to improve the speed and reliability of computer systems, further set him apart from those without research experience when he applied to graduate school. When he arrived at MIT, Lethin channeled his experience building special computers into his work as a research assistant in the artificial intelligence lab.

Today, Richard Lethin’s role as president of Reservoir Labs occupies most of his time. The company works to develop security and communications computer technologies for commercial and government customers. When asked about the differences between being president — a position Lethin has held for more than 18 years — and being an engineer, Lethin compared working at a company to eating from a plate of food. Engineers with different specialties eat only one course, whereas the president has some of everything, ensuring that the different dishes complement each other.

Lethin can also provide an insider opinion about the current state of progress in artificial intelligence and software engineering. Even since he began teaching 15 years ago, Lethin has observed artificial intelligence evolve from a topic viewed as a controversial subject to a valuable, mainstream idea. Not only are companies now investing in the development of artificial intelligence, but popular culture is capitalizing on the public’s interest in intelligent machines. “I don’t really have an opinion on transcendence or when it’s going to happen, but it sure is interesting. Even if machines don’t achieve intelligence equal to humans soon, they’re getting smarter every day,” Lethin said.

If an eager student in Lethin’s class were to ask him which of his roles is his favorite, he might answer that his favorite is being a father. But if you were to ask his favorite area within computer science, he would be unable to choose. “There are so many interesting things going on right now,” he said, “so there are just not enough hours in the day.”

Cover image: Image courtesy of John O’Donnell.