A recent study conducted by professor Becca Levy’s lab found a link between negative views on aging and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. This research has the potential to improve current knowledge of the disease by shedding light on new targets for prevention.

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease remains an active area of research. Some evidence indicates that Alzheimer’s traces back to a genetic mutation causing damage and death of neurons. Often, Alzheimer’s patients develop amyloid plaques, which are groupings of protein fragments that interfere with communication between cells. Disease sufferers may also have twisted fibers inside their brain cells, limiting the nutrition that reaches their neurons. While the biological basis, or biomarkers, for the disease is still being studied extensively, potential environmental causes are often overlooked.

Levy’s research examined the relationship between a person’s perception of aging and the presence of Alzheimer’s biomarkers. To do so, participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging were monitored over many years for their views on aging and their brain development.

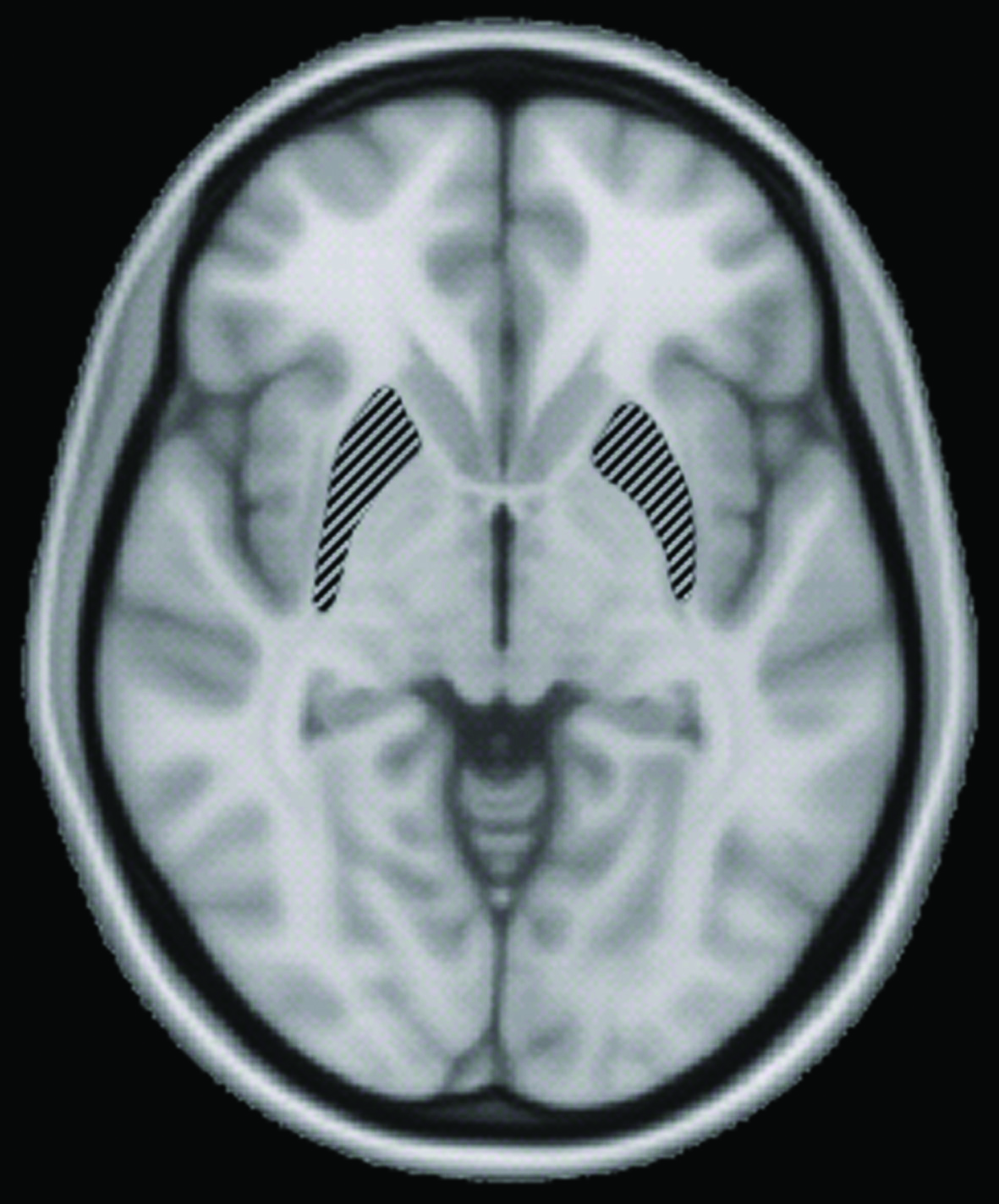

The participants in the study took a survey gauging their beliefs on aging and subsequently underwent MRI scans looking for changes in hippocampal volume. The hippocampus is an area of the brain involved in the storage and processing of memories. This makes decreased hippocampal volume a good indicator of the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, many volunteers who participated in the study posthumously gave their brains to science, allowing researchers to conduct brain dissections and look for the two primary Alzheimer’s biomarkers, plaques and twisted fibers. Researchers found a correlation between negative age stereotypes expressed on the survey and the progression of Alzheimer’s as judged by the presence of these biomarkers.

Levy commented that studies in animals revealed similar results to those found in humans. “Studies that have placed animals in stressed environments have seen an increased incidence of plaques and tangles. We were anticipating this relationship between stressors—in particular, stress that might be caused by the negative age stereotypes that individuals take in from their culture and these Alzheimer’s biomarkers in humans,” Levy said.

Another researcher involved in the study, biostatistician Martin Slade, supported this notion. “Your views of life affect how you take things in and how your body reacts. The more stress you put yourself under, the more your body will respond to it in a negative way,” Slade said.

In contrast to current Alzheimer’s treatments, which focus on molecular approaches to treating the disease, this study highlights a new potential target. Slade explained that the applications of the research to the real world are easy to implement. “On a daily basis, people are bombarded with negative age stereotypes in advertising and on television. By reducing these age stereotypes that are presented to the general public, we can potentially reduce the frequency and severity of stress-related disorders like Alzheimer’s,” Slade said.

Concurrently, Levy explained that people often form stereotypes early in life and maintain them as they grow older. She suggested that reinforcing positive age stereotypes in children as young as three or four years old could have a profound impact on their development and health. In fact, Levy and her team conducted another study in which they subliminally provided positive notions about aging via a computer program. They discovered that reinforcing positive age stereotypes that were already present had a beneficial effect on cognitive function. In this way, bolstering previously-formed positive age stereotypes may also help combat stress-related disorders.

When asked about their next steps, Levy and Slade both cited the importance of finding a biological link between negative age stereotypes and Alzheimer’s disease in order to find a molecular target for Alzheimer’s prevention. They speculate that biological stressors may play a role in linking negative age stereotypes and disease onset.

“While we were expecting these results, it’s still surprising when you have a theory and it turns out to be true—especially research which has such significant implications,” Slade said.