Doctors and scientists across the globe are frantically attempting to understand and challenge the latest public health crisis, the Zika virus. The virus has begun to garner as much widespread attention and fear as the Ebola virus did for much of 2015. Like Ebola, the Zika virus is completely unfamiliar to most people in the Americas, regions newly afflicted by the disease. What has caused this sudden outbreak and subsequent frenzy?

First identified in 1947 in rhesus monkeys, the Zika virus was found in humans in Uganda and Tanzania half a decade later. These humans were likely bitten by mosquitos that were infected with the virus. Mosquito bites remain the main mode of transmission of the Zika virus today, though it is also sexually transmitted.

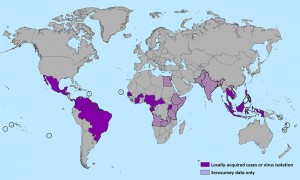

Prior to 2015, outbreaks had been confined to areas of Africa, the Pacific Islands, and Southeast Asia. But in May 2015, that all began to change: for the first time, reports of the Zika virus surfaced in Brazil. Researchers are still unsure about how this virus manifested itself in the Western Hemisphere. They suspect that large gatherings, such as the 2014 World Cup of Soccer and the 2014 World Spring Championship canoe race, may have facilitated spread of the disease. As a result, the Pan American Health Organization issued an alert to warn inhabitants of the Americas about the Zika virus.

Scientists are scrambling to learn as much as they can about the virus. The time required for the Zika virus to be detected in the body—also known as the incubation period—is likely a few days. Blood and urine tests can be used to confirm the presence of the virus. Scientists detect the Zika virus using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactions. This technique amplifies pieces of RNA—the Zika virus’s repository for its genetic information—such that they can be readily characterized in the lab. Symptoms of the disease, such as rash and fever, are generally mild, lasting a few days to a week.

The Zika virus has not been making headlines because of these symptoms alone. The virus has also been linked to birth defects, stemming from pregnant women who had the disease. The most common of these defects is microcephaly, in which the newborn has an abnormally small head and an underdeveloped brain. The mechanism for how the Zika virus can spread from a pregnant woman to her developing child is currently under intense study in the laboratory.

There is also no effective cure or vaccine for the Zika virus. At this point, the best preventative strategy against the virus is to reduce contact with mosquitos. One tactic for this is eliminating the areas in which these mosquitos can breed, such as stagnant pools of water. Buckets, pots, and other containers should be covered or safely stowed away.

Much research is still required in order for the Zika virus to be more rigorously prevented. Time is not on the side of the scientists. Thirty-five travel-related cases of the Zika virus have been reported in the United States. The number is expected to climb, especially in areas with climates similar to that of South America, including Hawaii and Florida. Furthermore, the World Health Organization has noted that the disease is “spreading explosively” in the Americas. By the end of 2016, up to four million people may have the disease. The Zika virus has devastated families across the globe; now, scientists must fight back with effective treatments. The stakes are higher than ever.