Despite recent snowfalls this January, the past fall and early winter months have been unusually warm. In December 2015, students roamed the Yale University campus with only light sweaters, passing by trees replete with flowers.

Many news outlets have deemed a strong El Niño, a warm phase of a larger periodic weather cycle, to be chiefly responsible for the mild winter weather. El Niño, however, is only one contributing factor; the polar vortices—low-pressure zones above the North and South poles—have played major roles, as well.

El Niño is part of a larger cycle of varying winds and sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific. Known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the cycle is divided into three phases. Each lasts approximately three to five years. The warming phase—El Niño—is marked by increased surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. Temperatures decrease in the cooling phase, which is called La Niña. The third phase is known for average surface temperatures, between those in the El Niño and La Niña phases of the cycle.

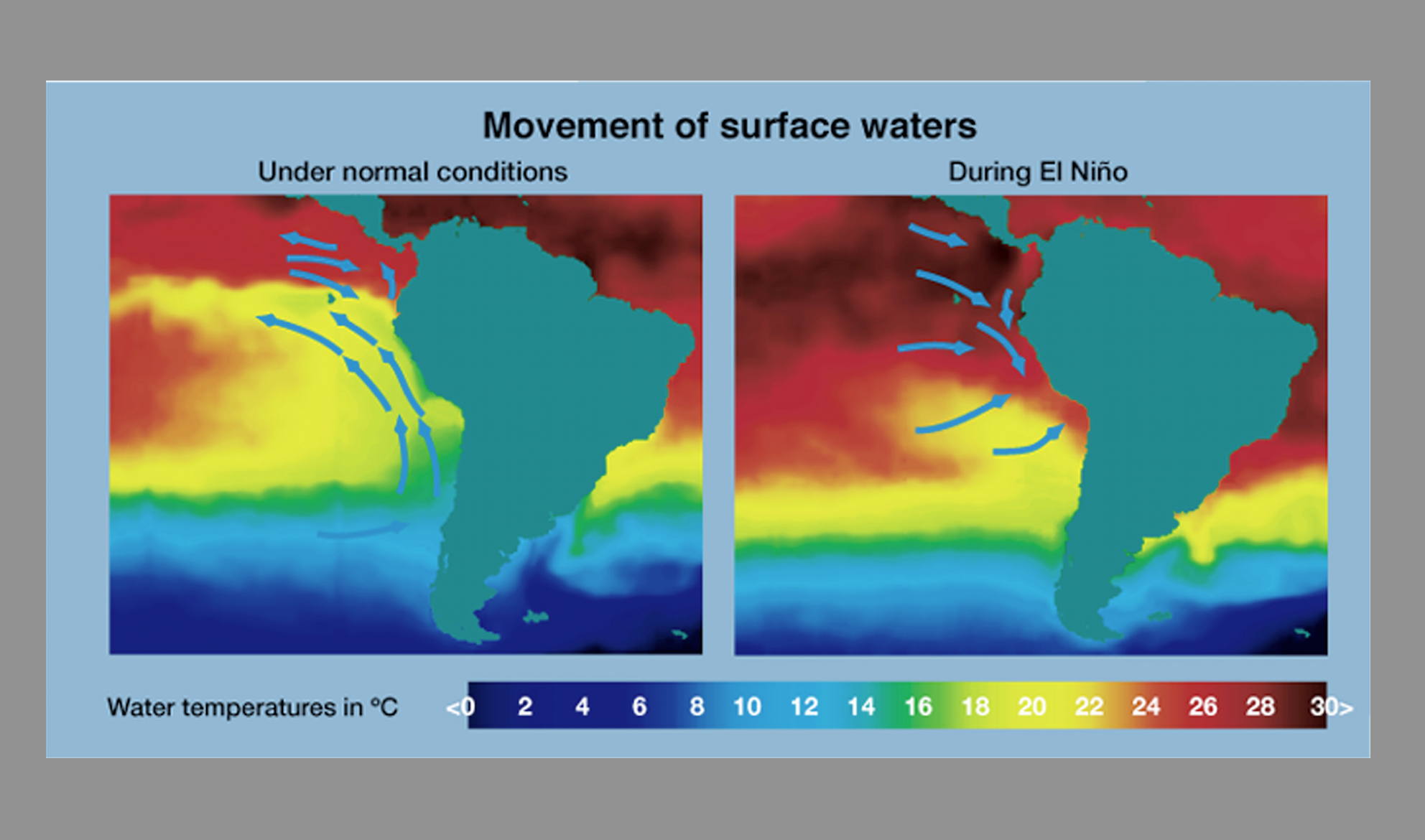

An El Niño phase begins when warm ocean currents move from the western Pacific Ocean to the northern coast of South America. As these currents continue to travel east, temperatures rise on the eastern shores of North America. Warm waters release more heat into the atmosphere, triggering global weather changes, such as flooding along the west coast of South America, and droughts in regions such as Australia and Indonesia.

The 2015-2016 El Niño appears to be one of the three strongest such phases on record. In December 2015, NINO3.4—a tool used to measure the severity of an ENSO phase— recorded ocean surface temperatures that were 2.38 degrees Celsius above average. By comparison, the 1997-1998 El Niño—the most powerful on record—recorded temperatures that were 2.25 degrees Celsius above average for the same time period.

Although the strong El Niño phase has played an important role in the rising temperatures along the east coast, the polar vortices have also been on scientists’ radars. The polar vortices are low-pressure zones of cold air at the North and South poles. They form due to temperature and pressure differences—exacerbated in the winter months—between the Arctic and the tropics. This past December, the Northern polar vortex was particularly strong. The vortex trapped more cold, Arctic air at the North Pole than usual, preventing it from traveling southward. As such, weather more germane to the fall season has continued into the winter months.

Though the polar vortex and El Niño have been particularly strong, this does not mean that students on the East Coast should trade in their ski goggles for sunglasses. Temperatures became significantly colder in late January 2016. The polar vortex often begins to weaken at this time, allowing cold Arctic air to escape southward and plunge temperatures lower.

Media furor, however, has yet to weaken. Such headlines about the intensity of El Niño and the polar vortex suggest that we are in the midst of a particularly rare weather occurrence. However, that is only the case if one only takes the past three decades into account. Expanding the time scale to the past few centuries, these changes appear more frequently. Our unseasonably warm weather is, in a sense, a regular irregularity.