When you grow up with three siblings, you quickly learn to treat groceries like a scarce resource. My sisters and I were particularly fond of Tropicana orange juice, no pulp. A carton never lasted long. I poured more for me, less for the others — that way, there would be more juice left for me to drink tomorrow. But if the carton was about to expire, if our mom threatened to throw it out, of course I would rather have my sister drink the juice than let it go to waste.

As it turns out, my sisters and I had a lot in common with monkeys.

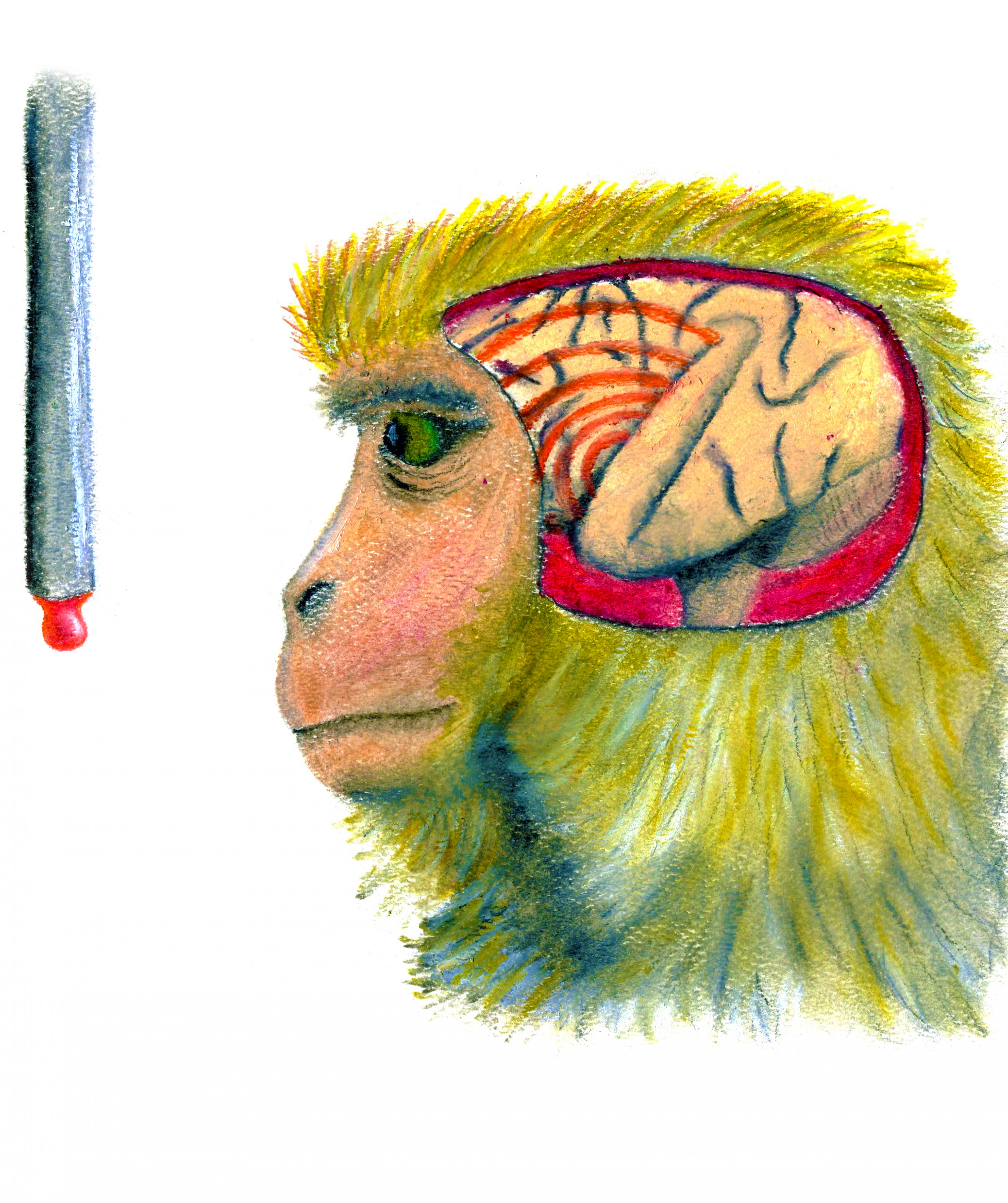

Steve Chang, a professor of psychology and neurobiology at Yale, had rhesus macaques play a dictator game: One monkey could decide how to allocate juice between himself and another monkey. Almost always, a monkey chooses to reward only himself rather than both him and his peer, even if he receives the same quantity of juice regardless. But if the choice is between his peer getting the juice and no one receiving it, he opts to reward the other monkey.

Rhesus macaques are inherently social. The cap on their generosity could be the need to compete for fluids in a natural habitat, which leads them to reward only themselves instead of self and other (and which caused some selfish juice hoarding in my childhood home). Chang and his team wanted to look deeper into these social decisions. They zoomed in on the brain while a monkey played dictator, uncovering the crucial role of the amygdala, value-mirroring neurons, and the hormone oxytocin.

Humans and primates are social creatures — we live in groups, form relationships, divide and distribute resources. For both of us, healthy cooperation is vital. Strong relationships and social status grant access to scarce resources. Some scientists have even suggested that empathy and generosity are the basis for advanced civilization. Understanding social decision-making is thus an important line of inquiry for researchers. Chang’s investigation of the brain structures that drive prosocial versus antisocial behavior could inform treatments for autism and other disorders linked to social deficits. More broadly, this research impacts all of us who inhabit a social world.

Empathy, hardwired

Early brain imaging studies found that the amygdala is active when someone experiences fear. For years thereafter, it was thought that the structure was only involved in aversion and negative reactions. In fact, the amygdala is a center for all sorts of emotions, and recent research has revealed its broader range of functions. “Our goal was to look at the amygdala and determine whether it’s involved in processing across self and other,” Chang said.

In short, the answer was yes. Chang’s findings add to our understanding of the amygdala and all that it does, and they offer a key piece in the effort to map a social decision across the brain.

The team took recordings from individual neurons in the basolateral amygdala, which is one unit of the whole structure. Chang outlined the possibilities: These neurons might only show a spike in activity when the monkey himself receives juice. In this case, the amygdala would be self-oriented, coding for personal rewards. Alternatively, the group might have identified some neurons that are active for personal rewards, and others that fire rapidly when someone else gets a reward.

Chang confirmed a third potential outcome: “The basolateral amygdala has neurons that treat value for self and other in a categorically same manner,” he said. The same neuron that fires more rapidly when I receive juice is activated by someone else receiving juice.

What the team found in the amygdala is a type of mirror neuron. But these nerve cells are not mirroring in the classical sense, when seeing someone scratch her head activates the same regions in my brain that would light up if I were to scratch my own head. Scientists are realizing that mirror neurons populate areas in the brain beyond motor cortex. Chang’s amygdala cells were mirroring value, and the suggestion is that these neurons might allow for emotional contagion, which occurs when someone else’s feelings affect your own.

Value-mirroring neurons offer a neural framework for empathy and generosity — they could explain our ability to feel for another person and our inclination to give. In humans, fMRI has displayed that another brain area, the ventral striatum, lights up similarly when you buy an item for yourself and when you donate to charity. Value-mirroring neurons could be a cue to someone else’s emotions, leading us to empathize with a friend’s pain and to feel good about donating money to someone in need.

“Our work squarely fits in with prior work identifying the amygdala in one’s own emotional experience,” said Michael Platt, a University of Pennsylvania professor and senior author on this paper. Amygdala neurons fired when a monkey received a reward, encoding a pleasant reaction. “It also supports the notion that your own emotional experience is the foundation by which you understand another’s experience,” Platt said. The same positive emotion-coding neurons were active when a monkey donated juice.

We have reason to believe that the human amygdala functions similarly. In addition to the social behaviors we share with rhesus macaques, several studies show overlap in biology and brain circuitry, Platt said.

According to John Pearson, a co-author on this paper and a professor in the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, value-mirroring neurons are important because they provide some clarity as to how the brain operates in value formation. How we define value is complicated. “If we’re both getting bonuses at the end of the year, I could be happy about my reward, or I could look at the situation as me getting less money than you,” Pearson said. There are multiple ways to assign value, and in all likelihood, both processes are happening in the brain. But now we know that certain neurons in the amygdala match value for self and other.

Neuroscientific studies, especially those with a brain imaging component, are vulnerable to the logical fallacy of reverse inference: When psychologists believed that the amygdala coded primarily for fear, noticing a spike in amygdala activity led to conclusions that the individual must be experiencing aversion. “What this paper adds to,” Pearson said, “is the diversity of processes we can associate with the amygdala. It’s much more than a fear center.”

A prosocial pick-me-up

Next, the researchers had monkeys play the dictator game after delivering oxytocin to the basolateral amygdala. The hormone increased prosocial behavior—monkeys were more likely to reward both self and other instead of taking juice only for themselves.

Prior research has pointed to oxytocin as a method to increase generosity. When people are given a sum of money and are asked to donate a portion to another player, they donate more after a dose of oxytocin. But in humans, it is impossible to target any hormone to one specific cluster of neurons, so these studies cannot elucidate how oxytocin is prompting prosocial behavior. Using the rhesus macaque as a model, the team highlighted the amygdala as a mechanism by which the hormone may be affecting the brain.

Chang’s findings are consistent with hypotheses at the forefront of the field, said Jennifer Bartz, a professor at McGill University who studies the nuanced effects of oxytocin on different populations and in different social situations. One prediction is that the hormone enhances our sensitivity to social cues. Indeed, Chang noted that dictator monkeys injected with oxytocin paid more attention to their counterpart. They spent longer looking at the other player. Perhaps in improving a monkey’s social gaze, oxytocin made the animal more generous.

Another explanation, Bartz said, is that oxytocin increases sensitivity to social rewards. In this case, the hormone motivates us to affiliate, because a social connection will boost our positive feelings. Value-mirroring neurons support this hypothesis, and perhaps oxytocin in the amygdala sparked the dictator monkey’s greater desire to be prosocial towards his peer.

Individuals with autism have trouble maintaining eye contact. They often struggle to intuit the mental states of other people, which is why empathy and generosity are challenging. Chang hopes that his findings are informative in helping people with social impairments, which includes autism, as well as conditions like schizophrenia and psychopathy. A few clinical trials in their early stages are testing oxytocin drugs on children and adults with autism spectrum disorder.

Although patients are excited about this, Bartz said we are still a long ways away from developing an effective oxytocin treatment. First, scientists must clarify the hormone’s mechanism of action, and they should explore how it influences prosocial behavior in different situations and for various patient groups. Bartz and her colleagues have found that oxytocin can exacerbate distrust in people with trust-related insecurities, which causes antisocial behavior.

Despite unanswered questions and technological limitations, the knowledge of oxytocin and the amygdala that has emerged from this research could eventually prove useful in treating individuals with social deficits. The causes of autism, schizophrenia, and psychopathy remain elusive. Pearson said this research elucidates the brain systems underlying a social decision, and understanding these systems is the first step to unveiling why and how they go awry.

Mapping a social decision

While the neural underpinnings of social impairments are still hidden, there are also many unknowns regarding the neuroscience of prosocial behavior. What does a social decision look like across the brain?

Chang’s prior work has zoomed in on other brain regions while monkeys play the dictator game. Neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex tend to fire in response to one’s own reward. “This area doesn’t seem to care much about what the other monkey gets,” Chang said. “So these neurons are selfish, in a way, or self-referenced.” In the anterior cingulate sulcus, neurons are most active when the dictator does not receive the juice, meaning these cells encode for a “foregone reward,” he said.

In the anterior cingulate gyrus, Chang has found a mix of cells. Many neurons in this area are other-referenced: they show the greatest activity in response to another individual’s reward outcome. But the anterior cingulate gyrus also contains self-referenced neurons that match the cells in the orbitofrontal cortex, as well as value-mirroring neurons that resemble cells in the amygdala.

Each of these four areas uses a different approach to calculate reward value between self and other.

“Then, they all come together magically to generate prosocial or antisocial behavior,” Chang said. “Evidence points to specialization in each of these regions, and now we need more insight into how these areas are talking to each other.”

The psychologists are also curious about the familiarity factor. How do value-mirroring neurons respond differently to close friends compared to strangers? If my sisters and I were reluctant to pour orange juice for each other, we definitely disliked sharing when people came over. The juice stayed within the family.

Some of Chang’s future projects will explore these areas as his team continues to sketch social decisions in the brain. There is still vast potential to accumulate new knowledge on the neuroscience of empathy, generosity, and prosocial behavior. Because how to share juice is just one of life’s many social decisions.

Extra Reading:

Chang, Steve WC, et al. “Neural mechanisms of social decision-making in the primate amygdala.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences112.52 (2015): 16012-16017.

About the Author:

Payal Marathe is a senior studying psychology and neuroscience. In past years, she has served as features editor and editor-in-chief of this magazine.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to thank Steve Chang, John Pearson, Michael Platt, and Jennifer Bartz for being so generous with their time in discussing these topics.