What are the sounds you treasure the most? Perhaps a loved one’s voice, a gentle piano melody, or the soft meows of a kitten? Unfortunately, sounds like these can fade away for us as we age. Studies have shown that after the age of 65, one in three adults has difficulties with hearing. This statistic increases to one in two adults after the age of 75. With modern medicine, the life expectancy in developed areas of the world is gradually increasing, meaning that among other potential health issues, many more adults will be susceptible to hearing loss.

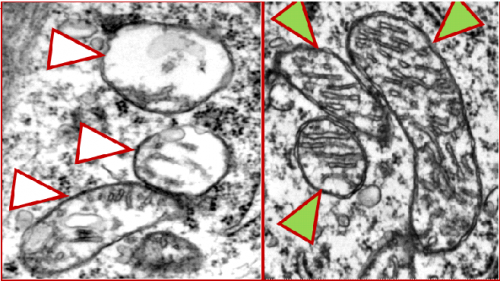

Although hearing loss during old age has many possible causes, Dr. Alla Ivanova’s research at the Yale Ear Lab has pinpointed one cause. Using specially bred mice, she linked a form of hearing loss to defective mitochondria in the cochlear region. She also identified an antioxidant-based treatment for this problem.

Mitochondria act as the engine of your ear, always running even when you’re asleep. Just as an engine of a car needs tune-ups, these mitochondria also need proper care and nutrition. To test just how vital these organelles are, Dr. Ivanova created mice with a genetic mitochondrial defect—removing a critical component from the engine. Scientists then measured the hearing ability of the mice over the course of their short lifespan of about 9 months to a year, replicating the aging process of the human body. At five months—equivalent to a young adult— mice with damaged mitochondria had impaired hearing. After a few more months, they couldn’t hear at all.

“Although mitochondria are hurt by excessive noise and toxins normally as you age, in these mice, [Dr. Ivanova] has enhanced the damage that occurs and exposed the relevance of mitochondria towards hearing loss and aging,” Professor Joe Santos-Sacchi of the Yale Ear Lab explained. Using this model, Dr. Ivanova was able to pinpoint exactly how much hearing loss was expected at certain ages when mitochondria are sick.

Dr. Ivanova’s research has focused not just in identifying the role of mitochondria, but also in repairing them when injured. She found that treating the mice with antioxidants, which remove potentially harmful oxidizing chemicals from damaging components of the cell, effectively reduced the strain on mitochondria and allow them to work for much longer—similar to giving a car engine an oil change. The mice that were treated with certain antioxidants, such as N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC), did not lose their hearing even as the other mice all became deaf. But unfortunately, just as any number of oil changes wouldn’t fix a broken engine, antioxidants couldn’t restore hearing in mice that were already deaf.

Although naturally occurring antioxidants like NAC are already available over-the-counter at pharmacies, they have not been linked before to preventing mitochondrial mutations that cause age-related hearing loss. Their use in human clinical trials could go a far way in enhancing our hearing and quality of life in old age.

One of the challenges of the experiment was figuring out how much the mice were able to hear. Unlike humans, mice cannot directly tell us how clearly they heard a word or a sound. The researchers utilized a methodology to address this problem based on the fact that our ears are always listening, even when we’re asleep. The mice were first put to sleep using anesthesia. By placing electrodes directly onto the mice’s skulls, they measured electrical signals from the nerve cells triggered by sounds entering their ears. Sounds caused visible peaks in activity within those nerve cells. Afterwards, the researchers could compare the activity graphs to identify and compare hearing loss caused by mitochondria.

Solving the role of mitochondria in the cochlear system of the ear is only part of addressing the causes of age related hearing loss. “The challenge is to separate the neural, immune and cochlear systems and figure out the impact of each component,” Dr. Ivanova said. Her future research will study other effects of these mitochondria in the aging process such as in the onset of Alzheimer’s.

Featured Image: An image of sick mitochondria used in the research with their functions significantly impaired. Image courtesy of Dr. Alla Ivanova