How an Alaskan quake helped advance earthquake science

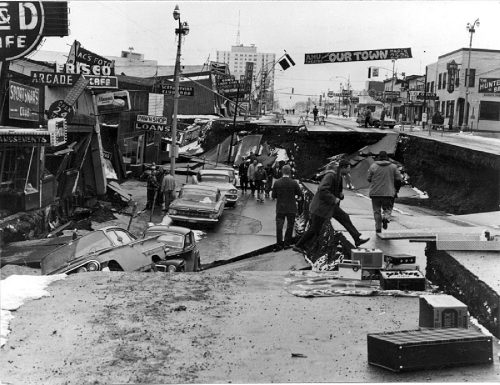

At 5:36 p.m. on Good Friday, March 27, 1964, a violent shaking disrupted a peaceful Friday night in the village of Chenega, Alaska. The villagers, primarily Alutiiq natives, noticed the water level of their cove rapidly recede, curiously exposing the bottom of the ocean floor. The villagers knew what it meant, but many of them did not have enough time to get out. Moments later, a thirty-five-foot-high wall of water came barreling towards them.

In a compelling tale of disaster, resilience, and scientific discovery, New York Times journalist and Yale graduate Henry Fountain tells the story of the biggest recorded earthquake in the history of North America in his new book, The Great Quake. After Fountain wrote an article in the Times about the quake’s 50th anniversary, an editor at a New York book publisher told him that the story sounded like a good book. Fountain quickly mobilized, and by the end of 2015, he had visited Alaska for a couple of months and completed most of his research. “I wanted to tell the narrative of the people affected and tell the tale of science through the eyes of George,” Fountain said.

George Plafker, a geologist who started with little knowledge of earthquakes but a lot of knowledge of the Alaskan backcountry, was one of the main players behind the scientific breakthroughs that the quake catalyzed. At the turn of the century, earthquake science was young and misguided. Eduard Suess, for example, put forth the leading earthquake theory of the time by comparing the earth to a drying apple that would wrinkle as it shrank. A small minority of scientists instead favored the emerging ideas—rejected by most—that would later become known as plate tectonics. It was not until after the Alaskan quake, however, that Plafker helped settle the debate.

The book tells the stories of the two communities that were hit the hardest by the quake: Valdez, a small costal town that arose from the Gold Rush, and Chenega, a village of around eighty native Alaskans and an American schoolteacher. Following these two villages through the disaster, the book is both exciting to read and informative. Fountain makes sure that no details are spared when it comes to the moments leading up to and just after the quake. He also details the months on end spent by many geologists, including Plafker, who dedicated their lives to understanding what happened.

Fountain closes his book with a sobering reminder: by several estimates, including Plafker’s, the Pacific Northwest is due for a megathrust earthquake—the same kind that occurred in Alaska. “The Northwest will probably have a quake like it in the next 50 years,” Fountain said. “They’re all expecting it to happen.”

References

Fountain, Henry. “The Great Quake: How the Biggest Earthquake in North America Changed Our Understanding of the Planet.” Crown Publishing: New York, 2017.