Alzheimer’s is everywhere. 5.5 million people are affected by this disease, and this number is predicted to double by 2050. The fear associated with Alzheimer’s has grown steadily with its rising media popularity, elevating Alzheimer’s research and education to an urgent level of importance. Due to gaps in our understanding of Alzheimer’s and an even greater lack of effective methods for evading its onset, studies on Alzheimer’s can be unscientific and speculative—exercise more, improve your diet, read more books. Maybe you forgot where you put your keys, or took two more minutes to find your parked car. Is this merely a forgetful moment or a sign of early symptoms?

One thing is for certain—the chances of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis increases with age. Fear of the unknown is understandable when there is so much uncertainty surrounding the nature of this disease. Research by a group at Yale might alleviate some of this anxiety. The group has developed a new imaging technique for measuring synaptic density in the brain and may be able to catch Alzheimer’s early. Besides being a technique for tracking Alzheimer’s as it progresses, this method could be used to evaluate reliable drug treatments–giving hope and confidence to a disease shrouded in fear and uncertainty. “We think this is a useful biomarker for evaluating therapy, and this will hopefully trigger more drug development,” claims Ming-Kai Chen, a member of the Yale research team.

Detecting Alzheimer’s: What a sick brain looks like

Alzheimer’s causes many changes in brain tissue that contribute to cognitive decline. Yet, early detection is difficult due to lack of reliable methods for differentiating between the biological changes associated with normal aging and early pathologic symptoms. One known method for early detection of Alzheimer’s is measuring an amyloid protein that accumulates and forms plaque in the brain. By forming deposits of plaque, amyloid may cause inflammatory responses that lead to cognitive decline.

Yet the accumulation of amyloid plaque is also characteristic in the process of normal aging, leading to the possibility of false positives and unnecessary stress in normal aging adults. “The challenge is the idea that amyloid may accumulate decades before symptoms,” said Adam Mecca, another member of the Yale research team. Another biomarker for Alzheimer’s is a protein called tau. Accumulation of this protein forms neurofibrillary tangles, which are toxic for the brain. In addition to amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, Alzheimer’s is characterized by synaptic loss leading to cognitive decline. “Amyloid deposits do not correlate well with cognitive impairment, whereas synaptic density may,” Chen added.

Imaging synaptic connections and Alzheimer’s

Synapses are connections made between nerve cells, so finding a direct way to measure synaptic density would provide a way to track the number of connections in the brain. Such a technique would be an important resource for detecting Alzheimer’s early, tracking its progression, and developing treatments. The mechanism for this disease remains unknown, but detection of these synapses in Alzheimer’s patients proves that there are many related parts that contribute to the cognitive decline of this disease.

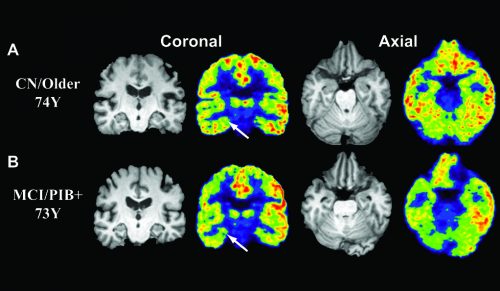

Until now, the effects of Alzheimer’s on synaptic density were measured only after death. Yet the Yale research group found a new method for detecting these changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: imaging the protein SV2A in the brain. SV2A is a synaptic vesicle membrane protein that regulates neurotransmitter release. Neurotransmitter release is how communication between neurons occurs. With the development of SV2A-PET imaging, researchers are now able to measure synaptic connections in the brains of living humans using tracers that bind to this protein.

Because the measurement of SV2A can indicate synaptic density and synaptic loss, it can be used to measure cognitive decline. Researchers used a radioactive tracer, called 11C-UCB-J, that binds to the SV2A protein, and set out to compare whether tracer binding of SV2A could be used as a quantitative measure of synaptic density. These measurements were taken using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans, an imaging test that uses radioactive tracers to detect targeted areas in the body. PET scans of patients injected with radioactive tracer 11C-UCB-J can detect SV2A and show how much is present.

Researchers found that patients affected by Alzheimer’s had a reduced amount of the tracer binding to SV2A in the hippocampus, a region of the brain involved with memory. This may be confirmation that the cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s is directly related to a reduction of synaptic density. Furthermore, the measurement of protein SV2A will help to evaluate changes in synaptic density overtime. This may lead to early detection of disease and faster drug development. “There is so much variability in this disease–in the way it progresses and in the exact types of symptoms people have,” Mecca said.

Prevention

Current medications for Alzheimer’s do not stop the progression of disease and have only a modest effect. “We do not recommend early treatment right now with current medications since there is no evidence that they help during early disease stages,” said Mecca. In addition, the potential benefit must be balanced with the possible negative side effects associated with medication use. For some patients, current medications are more of a burden than an aid. “Once the patient has lost a lot of synaptic density, it may be too late,” Chen said. As a result, future treatments may need to begin as early as possible. The earlier that experimental treatments may begin, the better chance there is for it to work.

Though amyloid PET is a great tool for detecting early signs of disease, and identifying a high-risk population, these scans are not helpful without effective preventive treatment. “People are very knowledgeable, [and] if they feel like they have something, they will find a specialist to check if it is really cognitive decline or just their anxiety,” Chen said. In this way, education for detecting Alzheimer’s symptoms is necessary, and self-awareness–differentiating between accidentally forgetting your keys on the way to work and getting lost on the way home after taking the same route every day for three years–is very important.

In addition to drugs, Alzheimer’s patients may be treated for neuropsychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, or irritability. Educating family members, finding resources for support, and enrolling in behavioral therapy are all methods for reducing the progression of this disease. For some, the neurodegenerative decline of Alzheimer’s seems to occur much faster than others. Those with a strong family history for this disease are at a higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s, but inherited genetic Alzheimer’s from a single gene mutation is extremely rare. “[Alzheimer’s] is an unavoidable disease unless you can really find what the cause for this disease is,” Chen said.

The research team hopes to increase the number of participants in this study and collaborate with other Alzheimer’s research teams to better study the measurement of synaptic density and cognitive decline–especially how synaptic density changes over time. In addition to studying synaptic density, these researchers are pursuing other projects to further explore the impact of other proteins and signals in the brain that contribute to Alzheimer’s. One project aims to use tracers to identify a relationship between neurofibrillary tangles and patterns of synaptic density. “There is a lot we can do to characterize this disease, and also some goals for developing tools that can help us to do good clinical trials to find disease cures,” Mecca said. The future of Alzheimer’s research is a positive one. With a better understanding for the mechanisms of this disease, there is a greater chance at detecting Alzheimer’s disease early and slowing its progression–and maybe even preventing it from ever occurring.