In Pau da Lima, the Brazilian epicenter of the 2015-2016 Zika epidemic, over seventy percent of the population was infected. Yet, across distances as small as twenty meters, there were large variations in risk of Zika infection. This differential immunity could be traced back to previous dengue exposure, as found in a recent study by the Yale School of Public Health and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

Zika and dengue viruses, both mosquito-borne, share many genetic similarities and often circulate in the same region. The relationship between dengue infection and susceptibility to Zika had been unclear in previous studies, but this study showed that in Pau da Lima—an area with high dengue exposure—dengue antibodies provided partial protection against Zika.

“Because vaccines are being developed for both dengue and Zika, a major concern was whether dengue infection produced good or bad antibodies in terms of Zika susceptibility,” explained Albert Ko, one of the study’s lead authors and department chair of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases at the Yale School of Public Health. The study emerges after pharmaceutical company Sanofi Pasteur’s controversial dengue vaccine put individuals without previous exposure at higher risk for severe dengue in October 2018.

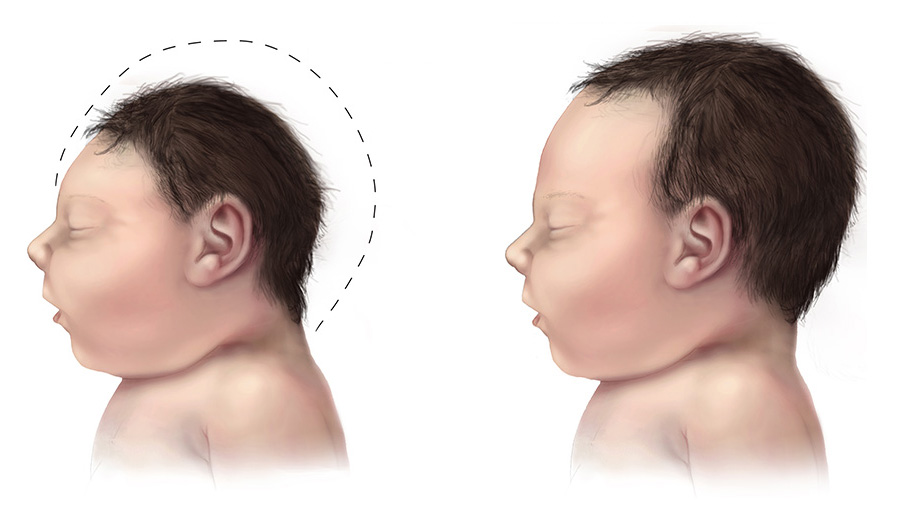

“The big question now is not only whether antibodies produced by past dengue infection protect [from] or enhance Zika infection in a pregnant woman, but also how those antibodies impact the likelihood of mother-to-child transmission and resulting risk for birth defects in the baby,” Ko said. Ko’s research proves especially important for global health after the CDC observed a twenty-fold increase in congenital microcephaly in Brazil after the 2015-2016 Zika epidemic.