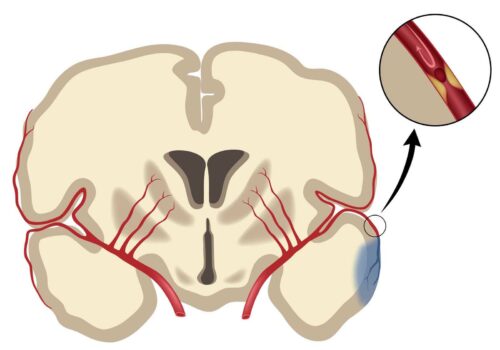

FAST: face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty, time. This acronym has been ingrained in us for the simple reason that it saves lives. Recognizing the signs of a stroke and immediately seeking emergency care is the first step in the right direction. But then what? In the case of acute ischemic stroke, a stroke caused by blockage of blood flow to the brain, medical practitioners have relied on the use of a lifesaving procedure known as mechanical thrombectomy. This amazing procedure relies on the insertion of thin instruments to suction out the occlusion at the source of the anterior cerebral artery.

Traditionally, this procedure functions on accessing the blocked artery through a rather circuitous manner. At what is known as a percutaneous transfemoral access point (near the groin area), an incision is made to insert a set of wire-like instruments into the blood vessels. With the help of a contrast agent directly injected into the arteries, surgeons can then guide the wires through the vessels starting at this groin area up to the affected anterior artery, located in the head region.

Although seemingly anfractuous, this odd method of approach has noteworthy benefits. “Most interventions for many, many years, were performed through the femoral artery in the leg, where if it’s damaged, your body can generally tolerate it very well without major issue,” explained Charles Matouk, a neurosurgeon at the Yale School of Medicine with extensive experience on the procedure. This way, the relatively simple design of the femoral artery and the redundancy of collateral pathways in this access point allow errors in the procedural execution to be less serious than if the procedure were performed at a different access point.

Still, there are limitations to this method of execution— most notably the dependence on a relatively clear path from the femoral entry point to the cerebral anterior artery. “The bigger issue comes when, as I say, the road is bumpy, or if you can predict the road is going to be bumpy from the leg,” Matouk said. In these cases, traditional mechanical thrombectomy is not possible and is a waste of critical time.

With this, Matouk and colleagues sought to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of other pathways, and, in a recent study, they tested and brought to light the efficacy of a carotid puncture as an alternative technique. The carotid arteries are large blood vessels in the neck that supply the brain, neck, and face with their blood supply. Because of their immediate proximity to the affected arteries of ischemic stroke patients, this entry point allows for many individuals who faced an unsuccessful traditional mechanical thrombectomy, or had the method pre-evaluated to be infeasible, a different opportunity for treating the stroke.

Despite the larger opportunity for error due to the complex nature of the artery, Matouk found that when put in practice, he very infrequently experienced errors. “It’s actually relatively straightforward, which I think is its beauty,” Matouk said. The process is very similar in approach to traditional, femoral mechanical thrombectomy in that it involves the extraction of the obstruction via a set of wires carefully maneuvered through the blood vessels. It differs in its extra precautions necessary: “We like the patients to be asleep with a tube in their mouth, so they’re intubated under an anesthetic because one of the complications that can arise when you puncture any blood vessel is that the closure doesn’t take and it can bleed.” With this approach, the build-up of blood in the neck can subject the patient to compression of the windpipe and possible closure of the airway, leading to asphyxiation. This intubation, plus the careful positioning of the patient’s head, is crucial for a successful operation.

When tested on patients unfit for a femoral approach, this alternative method proved to be extremely effective, with sixteen of the nineteen patients treated exhibiting the successful reoxygenation of affected tissue, where blood access had been thwarted. Additionally, after twenty-four hours, patients displayed smaller infarct, or dead tissue, volumes; they also had an increased likelihood for a lower and thus better mRS score, signifying that these patients were more fit according to the Modified Rankin Scale for Neurologic Disability.

In the future, Matouk hopes to see this approach become more widespread and more accessible to the many individuals for which femoral mechanical thrombectomy is unworkable. He and his colleagues are also looking into formalizing a concrete method to test for whether or not traditional thrombectomy works for an individual.

Citations

Carotid Artery (Human Anatomy): Picture, Definition, Conditions, & More. (n.d.). WebMD. Retrieved November 5, 2020, from https://www.webmd.com/heart/picture-of-the-carotid-artery

Cord, B. J., Kodali, S., Strander, S., Silverman, A., Wang, A., Chouairi, F., Koo, A. B., Nguyen, C. K., Peshwe, K., Kimmel, A., Porto, C. M., Hebert, R. M., Falcone, G. J., Sheth, K. N., Sansing, L. H., Schindler, J. L., Matouk, C. C., & Petersen, N. H. (2020). Direct carotid puncture for mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients with prohibitive vascular access. Journal of Neurosurgery, 1(aop), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.5.JNS192737

Matouk, C. (2020, October 30). Direct carotid puncture for mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients with prohibitive vascular access [Online interview].

Modified Rankin Scale for Neurologic Disability. (n.d.). MDCalc. Retrieved November 5, 2020, from https://www.mdcalc.com/modified-rankin-scale-neurologic-disability