Image Courtesy of Noora Said.

Consider a Thanksgiving dinner where your mother asks you to set the table. She tells you to put out the square plates, the nice water glasses, and the large napkins. But when you go into the kitchen, you find that there are multiple square plates, you have forgotten which glasses your mom likes, and the napkins are all the same size. You guess which ones she wants and bring them all out. Unfortunately, all your guesses were wrong. You’ve let your mother down. And now Thanksgiving is off to a highly traditional start—all because of an issue in communication.

Communication is fundamental to the functioning of our society, but too many of us often fail to use it effectively in our interpersonal interactions. Researchers in psychology like Yale University’s Julian Jara-Ettinger and the University of Oslo’s Paula Rubio-Fernandez are deep in the weeds trying to understand what underlies this miscommunication. Most recently, they have focused on studying how our minds use linguistic communication to reference objects. Through their research, they hope to learn how we come to know what is in another person’s mind.

The Experiment

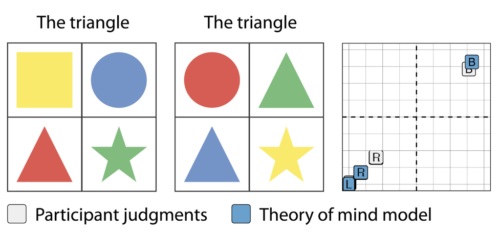

In a series of three experiments, Jara-Ettinger and Rubio-Fernandez presented participants with a virtual trackpad that has four quadrants, each containing an object. For the first two experiments, this object is a simple shape. Its size and color vary from quadrant to quadrant. Participants also see a line of text that refers to one of these objects—for instance, “the rectangle”—and are expected to click on that object. The participants are informed that these directions are written by someone who cannot see the contents of one of the four quadrants (‘the director’). The participants’ mission is to deduce where the blindspot is. Variations in the words used to indicate the target object may give clues.

Consider a situation in which there are two rectangles of different colors on the screen, but one of them lies within the director’s blindspot. The director will indicate “the rectangle” rather than “the blue rectangle” because it does not know it needs to distinguish between colors, only between shapes. This principle of not giving more information than necessary is known as a Gricean maxim of communication.

Each time after selecting the target object, participants also identify the quadrant they believe constitutes the blindspot. They indicate their confidence about both choices by clicking closer or further away from the center of the screen, which would indicate complete uncertainty.

Rubio-Fernandez explained that the research team wanted to create an experiment that would ask people to work through linguistic ambiguity in the same manner that they would encounter ambiguity in the world. “They use what the other person knows, which objects they know about, and take into account whether or not the other person uses adjectives contrastively or not,” Rubio-Fernandez said. “These three factors should allow someone with good social cognition to figure it out.”

In the first experiment, the directions describe the target objects with adjectives regarding their shape and color. These are considered absolute adjectives because they have a fixed meaning—a “red cup” looks red regardless of what color the cups around them might be. The second experiment repeated the process of the first but used size adjectives with a relative meaning. For example, when told to retrieve a “small cup,” one would return with different cups depending on how big the surrounding cups are.

The second trial had an additional layer of uncertainty. The directions in this trial had some unknown propensity to use adjectives even though they would not be helpful in distinguishing between possible targets. For example, the director may ask for “the small triangle” even when there is a display of all different shapes. This conditions the participant to believe that the director uses adjectives like “small” where it is not necessary. Therefore, if the display later shows a new arrangement of shapes and asks for “the small rectangle,” the participant cannot know whether the word “small” is being used to contrast one rectangle from a second, thus making it harder to pinpoint the blindspot.

The third experiment replicated this experimental paradigm with real world objects rather than simple colored shapes.

Models of the Mind

To understand how participants used language to identify the blindspot, the experimenters created two probability-based computer models that would go through the same trials as the human participants. They based these models on two different theories of how a person might try to approach the task.

The first model was based on a concept in psychology known as the “Theory of Mind”. Jara-Ettinger explained the model in terms of our interview conversation. “You’re representing what’s happening in my mind,” he said. “When you’re talking with me, you realize that I’m not just some regular object like a glass of water on a table. You have a very strong sense that there’s a mental life inside of me. It’s not just a curiosity; it’s what you use to make sense of my behavior.”

“Theory of Mind” is the process of internally modeling the mental life of another. “It’s a huge space of possible things that range from you knowing nothing to you knowing everything to you knowing some parts of things,” Jara-Ettinger said. “Then I can figure out, ‘okay, so under which states of knowledge would your words make sense?’”

The first model, then, included three parameters: the random chance that the target object would be in the chosen quadrant (a one in four probability), the increased random chance that it would be in one of the quadrants visible to the director (a one in three probability), and the probability that the director was using as few adjectives as possible. The model calculated the last parameter based on the director’s word choice in each experiment. This last probability factor allows it to consider the likelihood that the director is using adjectives unnecessarily, thus presenting a model of the director’s mind.

The second model, or the “deductive” model, is much simpler. It used only basic logic like “the blindspot cannot be one of the indicated squares” to identify the blindspot. Because this model lacks the final probability factor from the “Theory of Mind” model, it can only reverse engineer the director’s intent. It does not imagine the set of possible beliefs that the director could have. Rather, it identifies which quadrants the director can see to guess which quadrant is out of their sight.

Our Minds

Jara-Ettinger and Rubio-Fernandez found that the “Theory of Mind” model was a great fit for the data derived from human trials across all three experiments, while the “deductive” model was not. Both the “Theory of Mind” model and human participants were relatively successful at locating the director’s blindspot. The high correlation between “Theory of Mind” and data from human trials suggests that it is likely that people use “Theory of Mind” in their everyday lives.

Jara-Ettinger said the results give us reason to marvel at the power of our minds. “If we designed the model to make the best possible inferences it can and participants are giving you identical answers, it seems that on average, participants are also giving you the best possible inferences,” he said.

But what does this mean for daily communication? If people are, in fact, relatively good at determining another’s blindspots, why is it that we miscommunicate so many times each day?

“It’s very surprising because it seems that one of the most salient things for us is that in conversation, we get each other wrong,” Jara-Ettinger admitted. But he then reoriented the question: “Yes, we do get things wrong, but we also just take for granted how often we get things right. We’re just so used to getting inferences very quickly that we just kind of ignore those.”

Further Reading

Keysar, B., Lin, S., & Barr, D. J. (2003). Limits on theory of mind use in adults. Cognition, 89(1), 25-41.

Sources

Jara-Ettinger, J., & Rubio-Fernandez, P. (2021). Quantitative mental state attributions in language understanding. Science Advances, 7(47). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj0970