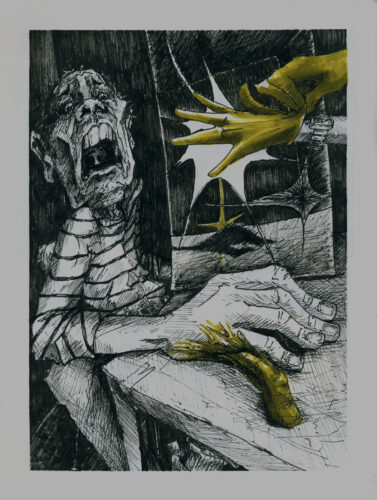

Image Courtesy of Uriel Teague.

“Perception is real, and the truth is not.” So said the wife of the late Philippine dictator in The Kingmaker, a 2019 documentary film. Although this quote embodies her distortion of the historical narrative surrounding her husband’s rule, it also describes how people are sometimes fooled by their senses. We commonly assume that our perceptions provide infallible information about our bodies and the world around us. The brain’s vast neural networks integrate senses—including smell, temperature, and light—to help us make sense of stimuli in our environment. For instance, we become aware of a burning fire through the smell of smoke, the heat it gives off, and the ringing of the fire alarm. Given that our bodies do not change drastically throughout our lives, our brains are accustomed to providing a unified experience of these stimuli.

However, recent research has suggested that we can alter how the brain represents the human body and trick it into perceiving the existence of imaginary body parts. Denise Cadete, a psychology Ph.D. candidate at Birkbeck, University of London, created a sensory illusion in which participants felt a sixth finger on their hand. To create this illusion, the participants placed their hands on both sides of a vertical mirror so that the reflection of the right hand would appear where the left was placed, with the left hand itself hidden from the participant. Experimenters then stroked each finger on both hands simultaneously, starting with the thumb and ending with the pinky finger. Finally, experimenters made twenty double strokes, one stroke on the table next to the right pinky and another along the outer side of the pinky.

Though the left hand remained hidden from sight, participants could see the reflection of the right hand where the left should be so that it looked as though the experimenter was actually stroking the left hand and the empty space next to it. As a result, many participants reported feeling a phantom sixth finger on their left hand. Furthermore, experimenters were also able to vary the length of this sixth finger. By altering the length of the strokes they made on the table, researchers created the sensation of a sixth finger fifteen centimeters long, or twice the length of the pinky, and 3.8 centimeters long, or half its length.

Reactions to this perception differed from person to person, but the word participants used most often was “strange,” even for those who did not report feeling a sixth finger. Matthew Longo, professor of cognitive neuroscience at Birkbeck and Cadete’s research supervisor, explains that this illusion comes from the “temporal synchrony” of the right pinky being stroked and the eye simultaneously seeing the same movement in empty space. “[These coordinated events] are a very powerful cue to the brain that there’s some causal link between these two things,” Longo said. “The parts of the brain that are integrating visual and tactile information aren’t interfacing directly with our high-level semantic knowledge. Instead, they are doing something more basic and automatic.” In other words, the brain does not use logic, reason, or language to make sense of stimuli. It’s as if the brain creates its own muscle memory to integrate sensory information quickly and automatically.

Given that our mental representations of the body are now known to be quite flexible, this study raises questions about the aim of creating prosthetic and robotic body parts. Should prosthetics be designed as replacement body parts trying to embody the appearance of the original counterparts? Or should they simply be tools, similar to Swiss army knives, each with unique functions? Cadete believes it is too early to tell, even though she and Longo were invited to tour Imperial College London to determine if this research can inform designs of robotic body parts.

What’s next? Cadete is now attempting to create the experience of a curved sixth finger. “In theory, it makes sense that we have some flexibility for [perceiving] length because our bodies become longer as we develop into adulthood,” she said. “However, the shape [of our bodies] is more or less the same throughout our lives.” Nevertheless, their results look promising. Though the line between perception and reality can sometimes be warped, it is likely that for the foreseeable future, we will not grow phantom fingers on our hands. That is, until evolution or robotic hands prove otherwise.