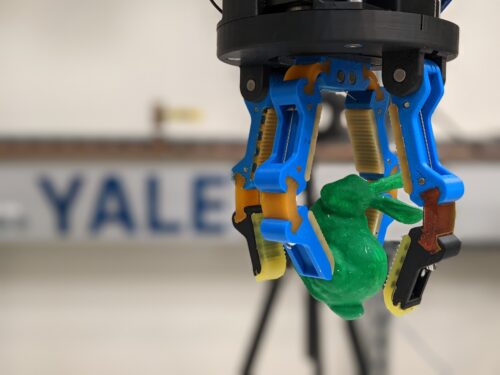

Image Courtesy of Andrew Morgan

Let’s say that you’re watching a video on your phone sideways when you receive a phone call. Instinctively, you use your hand to turn the phone upright, then bring it to your ear. While this may seem simple, the human hand, complete with its twenty-one joints, is incredibly sophisticated. In fact, it is one of the defining features that distinguish us from other mammals.

Spearheading the effort to mimic human dexterity in robots is Andrew Morgan, a PhD student working in Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science and Computer Science Aaron Dollar’s lab—the GRAB lab. Morgan described modern advancements in various areas of robotics, including computer vision and locomotion, but emphasized the decades-long challenges facing in-hand object manipulation, especially with the inherent uncertainty in any environment.

In their study, Morgan and his team developed an algorithm that enabled a four-fingered robotic hand to manipulate objects using a ‘finger gaiting’ process. “Finger gaiting is getting each finger to independently remove its contact from an object, move to a new location, then re-establish contact there, considering the timing of each event,” Morgan said. Furthermore, their programs could be applied to objects of diverse geometries, from simple cubes to complex concave objects. Being able to manipulate, re-grasp, and reposition objects is the key to performing tasks with the same flexibility as a human hand.

The implications of Morgan’s study are far-reaching. “Being able to mimic human dexterity will allow us to create human-like robots that can work in service settings […] such as folding laundry and washing dishes for elderly communities, and even for search-and-rescue missions,” Morgan said. Ultimately, Morgan and the GRAB Lab are on the path to developing robots that go beyond fixed roles like factory assembly lines, instead making them familiar with environmental uncertainties so they can serve more general and meaningful purposes.