At the forefront of food allergy research lie mighty defenders of the body: high-affinity immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. These antibodies, produced by the immune system in response to harmful substances known as allergens, are key mediators of allergic responses such as anaphylaxis—a severe allergic reaction affecting breathing and circulation. Despite their significance, IgE-producing cells are transient, raising a critical question: what is the mechanism that sustains and replenishes this essential cell pool that drives allergic responses?

A recent study led by Miyo Ota, a senior scientist at the Applied Biomedical Science Institute, explored the role of a specific subclass of memory B cells, called CD23+IgG1+ memory B cells, in food allergies, especially in children with peanut allergies. These memory B cells can quickly generate antibodies and retain pathogen-specific memories, which are vital for prolonged allergic responses. The study found that the memory B cells could become IgE-producing cells when triggered by a recognized allergen or pathogen. “Individuals with allergies have unique memory B cells responsible for long-term IgE reactions,” Ota explained. These memory B cells are equipped with receptors that mediate allergic inflammation, allowing them to sustain allergic reactions. Ota’s team highlighted that the ability of these allergen-specific memory B cells to switch to IgE production mode is critical for the prolonged severity of peanut allergies.

A clinical trial at Mt. Sinai is currently exploring the use of Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors—drugs that target a family of enzymes critical for immune response signaling—to treat food allergies, including peanut allergies. Ota suggests that this trial may provide valuable insight into whether JAK inhibitors could not only temporarily reduce IgE levels but also target the precursor memory B cells to potentially offer a long-term treatment strategy for food allergies.

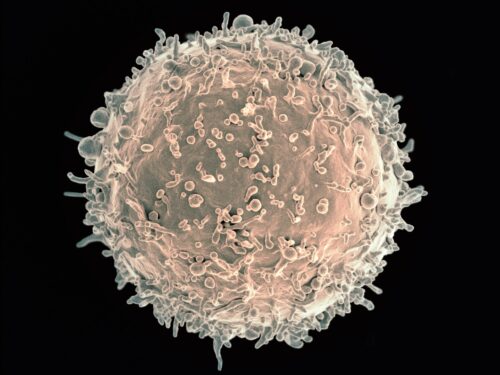

Image courtesy of Flickr.