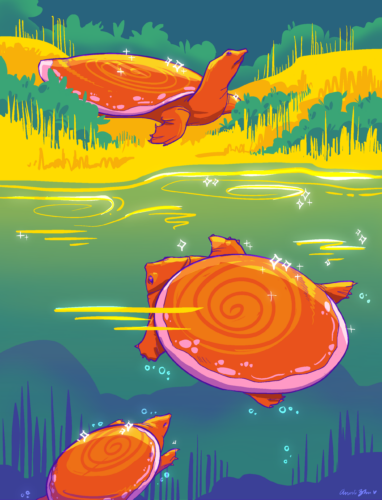

Art Courtesy of Annli Zhu

In the tranquil depths of Southeast Asia’s winding waterways dwells Cantor’s giant softshell turtle, Asia’s very own silent sentinel. Unlike its close kin, the sea turtle and the terrestrial tortoise, this turtle boasts a soft shell draped in leathery skin. With a flattened, pancake-like body and a long, tubular snout, Cantor’s giant softshell turtle possesses an otherworldly appearance. Typically found half-buried in the riverbed, the nocturnal creature has rarely been detected by ecologists in India until the authors of a recent paper utilized local ecological knowledge from communities along the Chandragiri River in Kerala, India to finally observe the mysterious creature in its natural habitat and determine its conservation status.

Cantor’s giant softshell turtle, Pelochelys cantorii, is listed as an Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species and is at high risk of extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. The species is protected under international law, and hunting or trade of the turtle within India is a punishable offense under a long-standing wildlife protection act. However, despite these legal designations, the population of the species in India has waned as a result of habitat destruction, illegal opportunistic hunting, and accidental killings by fishermen. “I didn’t even know soft-shelled turtles existed until I was in my early twenties,” described Ayushi Jain, a current PhD candidate at the University of Miami and the first author of the paper. When Jain once distributed an online survey to residents across Kerala, she found that only about five percent of six hundred respondents even knew what a softshell turtle was.

Funded by the EDGE of Existence Fellowship, Jain was determined to unravel the mysteries surrounding the turtle’s behavior and population distribution. However, almost immediately, she ran into an obstacle: the only records among the sparse literature of Cantor’s turtle sightings in India were anecdotal. Working with Francoise Cavada-Blanco, a senior teaching fellow at the University of Portsmouth and Jain’s mentor, Jain began her project acknowledging the very real possibility that the turtle had gone extinct in India. “Even if we were unable to observe an individual, speaking to the community would produce valuable information about the species historically,” Jain said. “We wanted to tap into that knowledge that is passed down through generations—what we call local ecological knowledge—and gain a better understanding of the behavior of the turtle.”

Over the next two years, Jain dedicated herself to living among the local community as she conducted interviews along the Chandragiri River. Working on a limited budget, Jain initially carried out chain-referral “snowball” sampling—interviewing participants who had seen the turtle and asking locals to refer other members of their community. In these semi-structured interviews, Jain listened to the stories of the local people as she collected data about the turtle’s seasonal habits, daily activity, and other ecological behaviors. Once snowball sampling ceased to provide further interviewees, Jain turned to opportunistic sampling as she slowly gained the trust of the local inhabitants and expanded her ecological survey. “The wider implication of the study, I believe, relies on the use of Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK) as a scoping step to refine and better design ‘conventional’ ecological surveys when working with rare species,” explained Cavada-Blanco when discussing their research approach. “This is not a novel approach, but one that has scarcely been used in freshwater and marine systems. This is mostly because naturally rare species usually have low detection probabilities when using conventional sampling designs.” Cavada-Blanco described how LEK can be a powerful tool in conservation studies, and Jain supported the idea that this bottom-up community approach was crucial to her success.

In one particular incident, Jain was informed by members of the community about a poaching incident that took place during her stay. “We informed the Forest Department that the incident had occurred. However, we couldn’t take action against them as no community member would ever trust us again,” Jain explained. Jain described the incredibly difficult tension commonplace in ecological conservation efforts: choosing between seeking justice for one poached animal or protecting numerous others through continued research. “After, the local community members came to trust me a lot,” Jain said. “They knew that they could tell me things, even if they have done something wrong, without having to fear I would go to the authorities and get them into trouble.”

Jain’s decision paid off. In the third month of her fellowship, she finally laid eyes on the majestic Cantor’s giant softshell turtle, guided by a local resident. Snapping a quick picture of the turtle, Jain allowed herself to simply observe the turtle as it surfaced for a few seconds. Jain basked in elation, having proven the continued endurance of the species in India. Over the next few years, Jain had several encounters with the species as she shifted her work towards the conservation of Cantor’s giant softshell turtle.

In this time, another challenge Jain faced was the language barrier—she had to rely on translators to communicate with the locals. Nonetheless, the trust she earned in these communities triumphed, facilitating the relationships that aided conservation efforts. Hosting awareness workshops, going house-to-house to hand out small information notebooks, and setting up signs and fencing around identified nesting areas, Jain spent another two years dedicated to conservation. Funded by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and The Habitats Trust, she conducted yearly turtle nesting surveys in the region starting in 2021 and oversaw the incubation and release of between forty and fifty hatchlings into the wild.

Beyond just the research, Jain’s lasting legacy in the region is the active alert network she helped set up among the locals via WhatsApp. “Human behavior takes time to change,” Jain said. “But, in my studies, the communities have really grown to be enthusiastic about protecting the turtle, and they even took it upon themselves to protect discovered nesting sites.” Currently working on her interdisciplinary PhD, Jain sits at the intersection of social policy and ecological conservation. Even as she now researches the policies behind dam management in freshwater ecosystems, Jain continues to keep in touch with the Kerala community and still looks for more grants to help fund the self-sustaining community effort to protect the magnificent giant freshwater turtle.

According to Cavada-Blanco, the power of local communities in conservation initiatives has been demonstrated across various cultures and contexts for numerous conservation objectives, including ecosystem restoration, species reintroduction, and threat reduction. However, this approach remains challenging as each intervention or program must be tailored to address the local cultural, socio-political, and economic environment, hand-in-hand with the biological and ecological requirements of the targeted species or ecosystems. “There is not a prescribed recipe for success,” Cavada-Blanco said. “However, LEK is a powerful tool to improve the effectiveness of conservation research and one that should be used more frequently in aquatic systems, given the deficit in financial resources available for the enormous list of species of conservation concern.”

“In truth, field scientists have always relied on local knowledge, even when they were busy ‘discovering’ species. But those roles were typically ignored or downplayed. It is a different world today with community science, indigenous knowledge and other sources and approaches being actively developed,” said David Skelly, the Director of the Yale Peabody Museum and a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology who is unaffiliated with the original work. “Just within the last few years, the incredible power that comes from tapping into local communities to help understand species and natural systems is finally being surfaced,” he said. Indeed, the focus on self-sustaining conservation efforts cultivated by Jain, Cavada-Blanco, and their team exemplifies a shift in the methodology of small-scale ecological studies. After helping to reveal the importance of human connection in science, Cantor’s giant softshell turtle can now rest easy in the depths of its shadowy rivers, protected by an invested and enthusiastic community.