The cosmos, where asteroids and other space junk often shoot through outer space at more than 22,000 miles per hour, can be a dangerous place. Astronauts who depart Earth and stay in spacecraft such as NASA’s International Space Station need protection from celestial dangers. Spacecraft currently achieve this security by using a configuration of more than 100 Whipple bumpers, which are essentially shields that vaporize any particles on impact before they do damage. Now, researchers at the University of Michigan led by Timothy Scott have created an even better way to protect spacecraft: a futuristic material that patches itself up after any hole is made, less than a second after the collision.

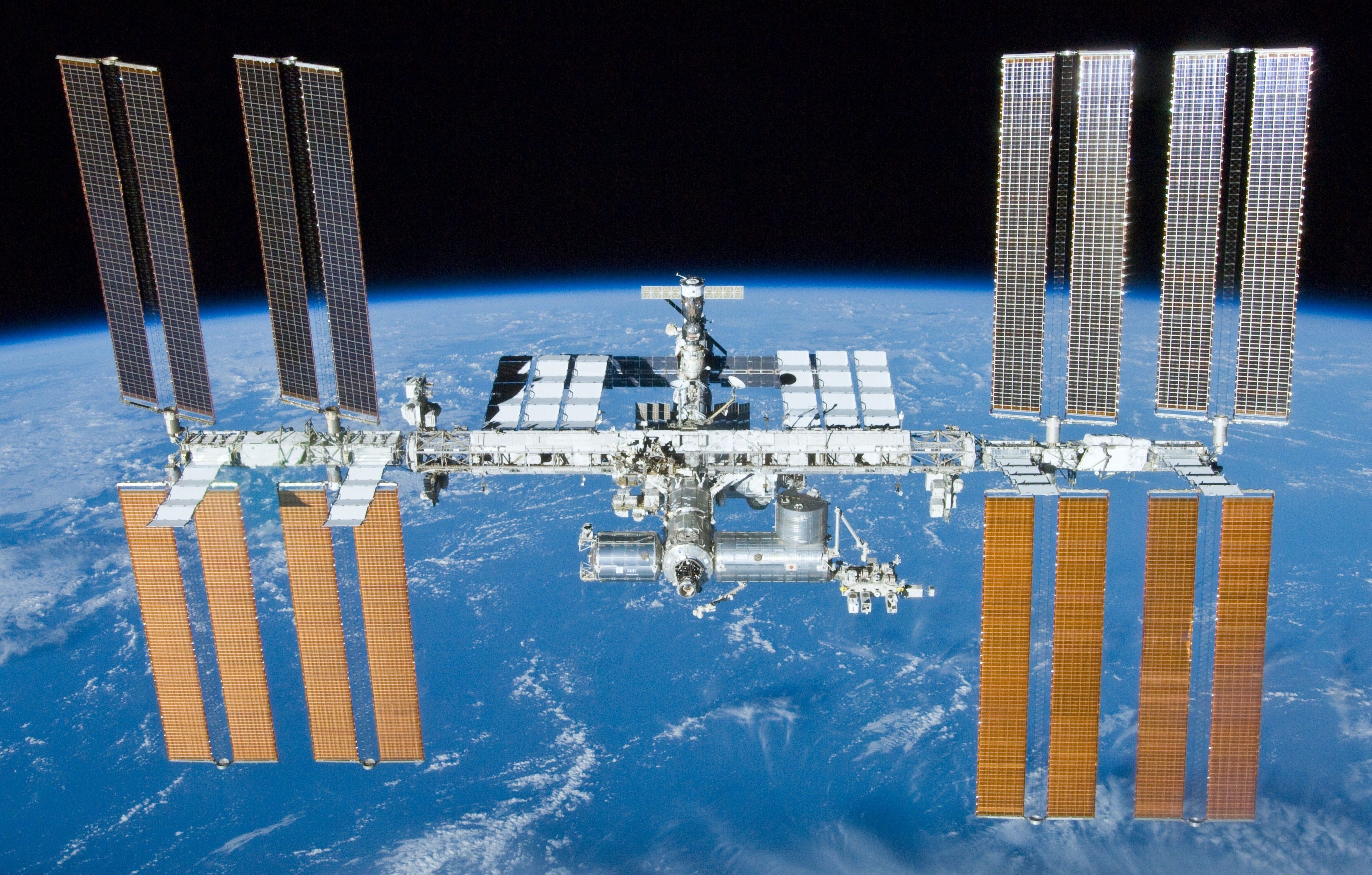

space debris. Image courtesy of NASA.

To demonstrate the efficacy of their new material, the scientists released a video testing their invention in a gun range, where they fired bullets into a sheet of the polymer. The bullets pierced the sheet, which then instantly repaired itself to cover up the hole. Theoretically, this material could be used to build the outer parts of a spacecraft, so that even if an asteroid were to hurtle through the walls, they would not be permanently damaged. Such a construction would be able to better protect manned and unmanned spacecraft.

The scientists created this autonomously healing material by making trilayered panels of a liquid resin sandwiched between two solid polymer layers. The secret to the material’s ability to repair itself is the liquid resin. When a high velocity projectile punctures the first solid panel, the resin pours into the entrance hole. The resin is now in contact with atmospheric oxygen, which causes the material to instantly solidify. The three layers remain intact and the hole in the wall is completely fixed.

This novel material comes with many advantages over previous attempts at creating self-healing substances. While it is not the first autonomously repairing substance to use liquid to solid transformations in some way, this new polymer is the first that can secure a breach within seconds. Previous materials required much more time to self-repair, making them unfeasible for real world use.

These polymer panels are also much lighter than the bumpers used by the International Space Station. This lightness is beneficial because it costs about $10,000 per pound of equipment being launched into space, so the self-healing material is cost efficient. Although the scientists still have to conduct tests mimicking the pressured conditions of space, the impressive qualities of this self-healing material indicate that it has massive implications for the future of aerospace engineering, not to mention other fields such as biomedical research and the automotive industry.

Cover Image: A view of the International Space Station, May 2010. Image courtesy of NASA.