People with schizophrenia experience an altered perception of the world. They might hear auditory hallucinations or have delusions. This can lead to symptoms of reclusive behavior and incoherent thoughts. But there is another important symptom often overlooked in discussions of schizophrenia: memory deficit.

Schizophrenia causes impairments in working memory, or the information held for short periods of time in the mind, as well as episodic memory, or details about personal experiences. That this disease would dramatically impact memory is not so far-fetched — schizophrenia affects a person’s reality, and reality is inseparable from memories. Previous studies have attributed memory deficits in schizophrenia patients to abnormal functioning in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an area near the front of the brain responsible for spatial memory and representation. However, a team of psychologists has published evidence that memory loss in these patients results because of a decline in general ability rather than localized memory domains.

Understanding how memory works in psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia is of growing interest to researchers, including Kristen Haut, lead researcher on the recent paper. Haut formerly worked at Yale and is now an assistant professor of psychology at Williams College. Her group has demonstrated a unique quality to the memory deficits that occur during schizophrenia, which could shift how doctors approach and treat the disease.

To determine if memory deficits were shared across psychiatric conditions, as previously predicted, the scientists established two control groups of patients with either bipolar or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. When these patients performed memory tasks, they fared better than schizophrenia patients. “Genetic studies have shown that risk for bipolar disorder is shared with schizophrenia and both show memory deficits during psychotic episodes. However, it turns out that deficits in schizophrenia were much more significant,” Haut said.

Moreover, all schizophrenia patients exhibited a similar level of impairment, with no particularly low-performing subgroup. The researchers concluded that these particular memory deficits are unique to schizophrenia, and generalized among sufferers.

These findings suggest new nuances to consider in treating schizophrenia. If the disorder affects memory of self and the representation of the world, this impairment could amplify other symptoms such as withdrawal or delusions. Such implications call for a revised treatment plan, tailored to memory deficits.

New evidence that the underlying neurobiology of schizophrenia is generalized paves the way for innovative approaches in fMRI studies and drug design, marking a new beginning for a misunderstood illness.

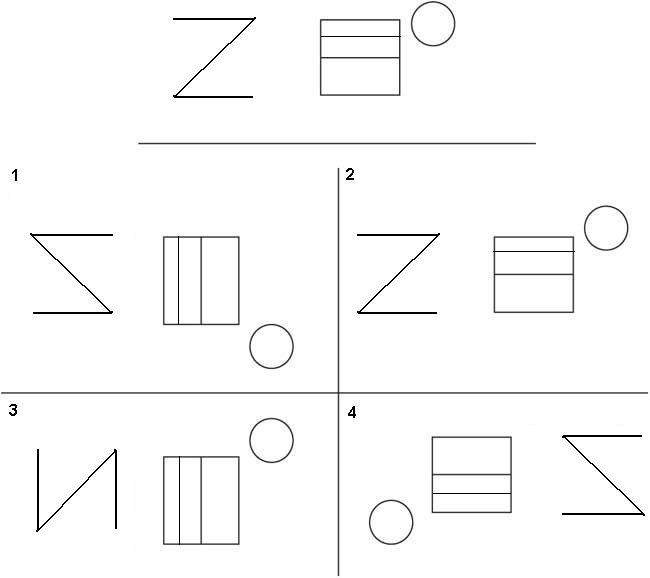

Cover Image: The Benton Visual Retention Task is frequently used as a test of visual memory. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.