To many, world peace might seem like a childlike concept entrenched in innocence. But maybe a focus on childhood is exactly what we need to work towards peace within communities.

Yale researchers have combined findings from multiple fields — including psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology — to champion early child development programs as pathways to peace. The researchers focused specifically on the potentially causal link between early childhood development and a culture of peace within families, communities, or even nations. The team found that providing group-based family support programs and engaging with fathers are both effective strategies to promote a peaceful disposition in children. But the positive impact of these interventions goes beyond a single generation. Encouraging peace during childhood, in turn, could reduce violence and bring forth peace for future generations as well.

“Child development is a huge and fascinating field of science,” said Catherine Panter-Brick, Yale professor of anthropology, health, and global affairs. “Another important and fascinating field is peace-building. Usually, these two fields barely intersect.” Panter-Brick and her team wanted to bridge this gap.

Over the past two years, both Panter-Brick and professor James Leckman of the Yale Child Study Center, have participated in a number of forums on promoting peace. These discussions and conferences are a part of the United Nation’s Early Childhood Peace Consortium, for which Panter-Brick and Leckman serve as lead members.

In these forums, Panter-Brick and Leckman have discussed the interventions that they believe will be most effective in promoting peace. Some strategies target parenting behavior, teaching parents skills on how to be sensitive towards their children’s needs and how to raise them without a violent disposition. Other initiatives harness the media and community leadership, as was done in northern Ireland to help end many decades of civil strife.

Panter-Brick emphasizes that the timing of interventions matters. “Acting early in the child’s life to promote health, competence, and empathy is far more effective than acting later to persuade young adults to turn away from violence,” she said.

At other UN events, Leckman has highlighted the biology of caregiving, pointing to the significance of hormonal changes as a way to explain the efficacy of early nurture in reducing violence over the course of a lifetime.

According to Leckman, epigenetics — the study of external effects on gene transcription and expression — has been shown to shape parental behavior in animals. Studies of Norwegian rats show that the amount of pup grooming behavior from mother rats corresponds to the amount of grooming they themselves had received as pups. Researchers are now confirming that in humans, a disposition to peace or to violence may also transcend across generations.

The team further highlights that group-based interventions are preferable to family-based ones because they promote empathy across ethnic, religious, and social divides. These strategies bring together groups of parents in the same place and time, rather than relying on solo families to access specific services.

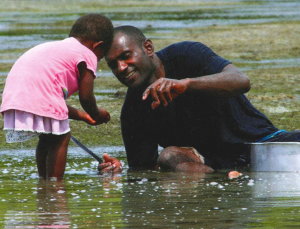

One illustration of group-based parenting interventions is the Mother Child Education Foundation, or AÇEV, an organization based in Turkey that offers programs for early childhood development. The programs were first designed for groups of mothers, and then at the request of women, were designed for groups of fathers and run as gender-specific Mother Support and Father Support Programs. After participating in the intervention, which aims to develop communication skills and positive parenting behaviors, many of the fathers involved became friends, despite coming from different religious and socioeconomic backgrounds. These friendships led to supportive communities that persisted to aid all parents with their responsibilities.

“There’s something transformative about people coming together to talk about their life experiences, sharing that information with others, and going through a curriculum where they report what they learned and how their interaction with their children changed,” Leckman said.

Now that these results have been established, future steps include translating these findings into effective programs in different social, economic, and cultural contexts, and scaling them up to reach more people. “The new message is that it takes political leadership to reach peace, but it also requires good science,” Panter-Brick said.