There are few more widely recognizable images in medicine than that of an MRI machine. MRI, which stands for magnetic resonance imaging, uses a magnetic field and radio waves to generate images of body structures. This procedure has an array of applications, from diagnosing tumors to detecting brain activity via changes in blood flow.

MRI scans may reveal more about the human body, and the brain in particular, than previously thought. A recent study at Yale University, led by graduate student Emily Finn and associate research scientist Xilin Shen, indicates that patterns of brain activity are unique enough to identify individuals with a high degree of accuracy.

The Yale team analyzed data from the Human Connectome Project, a database of MRI imaging results available to researchers. They used this information to perform a connectivity analysis, creating a “connectivity profile” of the unique brain patterns of each individual in the study. Using connectivity analyses, the researchers were able to determine the identity of individuals through their connectivity profiles with up to 99 percent accuracy. The discovery may have applications in the clinical realm, with the potential to eventually be used in the early diagnosis of mental disorders.

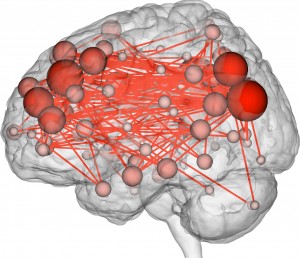

The method of analysis was novel, in part, because the team deviated from traditional methods of analyzing functional MRI (fMRI), a technique used to measure the activity and understand the function of different brain regions. Past fMRI studies had been concerned with measuring activity changes in single regions. Instead, the researchers studied activity levels throughout the entire brain. They divided the brain into a network of 263 nodes and monitored how closely activity levels between each node corresponded with one another. If two nodes were more active at the same time, then those regions were considered “functionally connected.”

Different regions in the brain function as a network, coordinating their activity; what surprised the researchers was the discovery that these connectivity profiles are highly individualized. This had not been shown in previous fMRI studies, which would average fMRI data across a large number of scans, thereby missing this personalization of patterns in brain activity.

“I think we are the first to show that you actually can find and use subtle features in brain connectivity to tell everyone apart,” Shen said.

The connectivity profiles, which resemble QR codes in appearance, can do more than simply differentiate individuals. They can also predict, with a certain degree of accuracy, levels of fluid intelligence: an individual’s capacity to solve problems and think logically.

Though the findings may evoke futuristic images of determining identity and intelligence via a brain scan, Finn and Shen both emphasized that the motivation behind the study was not to develop an entirely different way to classify individuals. People are still much more easily identified by sight or fingerprinting. Fluid intelligence is still more practically determined by IQ tests.

“The interesting finding here was we could identify people no matter what they were doing while they were in the scanner, and that sort of goes against a lot of the traditional fMRI research, which is based on the assumption that if you’re doing different tasks, your brain looks very different,” Finn said.

Photo credits: Jerry Domian

Future studies will investigate the use of fMRI imaging for early diagnosis of mental disease, Shen said. Currently, disorders such as schizophrenia are not readily diagnosed until they have fully developed. Functional connectivity profiles may eventually offer a way to determine whether an at-risk individual will develop these diseases. The researchers hope that further studies using “brainprints” will reveal a way to differentiate mental disorders in their early stages or to predict the eventual severity of mental disease.