Immunotherapy has become a new tool for treating cancer. Using the processes that attack pathogens, researchers have discovered treatments that in some patients’ transform cancers from life threatening to manageable conditions. However, in many patients with several types of cancer, the immunotherapy stops working or never works at all. The reasoning being that many cancer cells can hide from the immune cells that might destroy them. Yale scientists have developed a new system to make those cancer cells more visible to the immune system and thus vulnerable to attack.

“Tumors are constantly evolving to various pressures in the body,” says Ryan Chow, a first author on the study published in Nature. Cancer cells have evolved to suppress antigen presentation, the process that alerts the body’s immune response to mutants. “A lot of the immunotherapies that are successful right now are working on relieving suppressant signals,” Chow states, “but what if the tumors don’t show anything on their surface at all that would normally activate the immune system? … instead of releasing inhibition… we are operating on side of making tumors look more weird to the immune system rather than lowering the threshold for the immune system to attack something.”

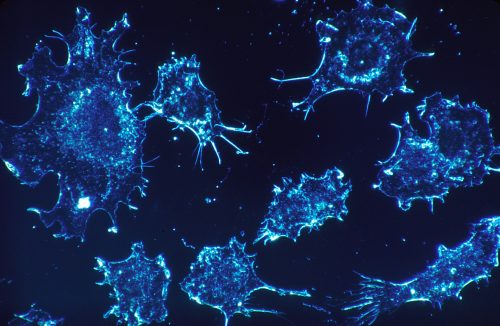

In order to make the tumors look “more weird,” that is more susceptible to immune destruction, the researchers developed a system they call Multiplexed Activation of Endogenous Genes as Immunotherapy or MAEGI. The novel process begins with putting the tools of CRISPR gene editing into many cells by attaching the tools to viruses that attach to the target cells. Using CRISPR, we are forcing “tumors to overexpress different genes…which is getting the immune system to recognize them and reject them.” Chow states. MAEGI treatment, then, marks the location turning a cold tumor (undetectable and lacking immune cells) hot and then recruits T cells for destruction.

Next the scientists used inactive cancer cells—called a cancer vaccine—to boost the immune response. This resulted in an increase in antigen expression, the process that alerts the body’s immune response to mutants. The response was positive: in preventive settings the tumors “were always rejected, so they could never actually grow out.” Chow states. In terms of therapeutic settings, “we injected inactivated cell vaccine into mice that already had the [tumor] and saw some effects against the established tumor.” The research is promising and further efforts have potential in preventative and therapeutic settings along with individualizing treatment. However, Chow hesitates to express overexcitement, “we’re still in the early stages”.

The research being conducted by these Yale scientists offers the potential to reform how we approach cancer treatment and more importantly how we aim to combat it. Cancer cells may be masters of avoiding detection, however, the work being done here shows that even the hidden can be found.