Image courtesy of Libertas Academica.

Ever felt anxious before a test or important presentation? Maybe it’s genetic. Researchers at the Yale School of Medicine and UC San Diego partnered with the Department of Veterans Affairs to study the genetic underpinnings of anxiety. The Million Veteran Program (MVP) is a nationwide study by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs that collected varied biological data on US veterans to form one of the world’s largest biobanks. Dr. Joel Gelernter and Dr. Daniel Levy, from the Yale School of Medicine, made use of this large genetic sample to understand the possible genetic causes for anxiety and its coincidence with other syndromes, such as depression, PTSD, and neuroticism.

Through a technique called a genome-wide association study (GWAS), Gelernter and his team tested associations between genetic markers and the traits of interest in around 200,000 participants from the MVP. GWAS was a revolutionary technique that allowed the researchers to uncover biology without the need for model organisms, such as mice. “What we hope to do is get at new biology to understand the disorder and where it comes from,” Gelernter said. GWAS looks at the difference in gene variation between people who are affected and unaffected by the disorder, and indicates the genetic markers that could be associated with it. An association by GWAS suggests, but does not prove, a relation to higher risk for the trait. In any case, this study is the largest GWAS of anxiety traits ever conducted. For a sample size of this magnitude, data collection and testing is challenging.

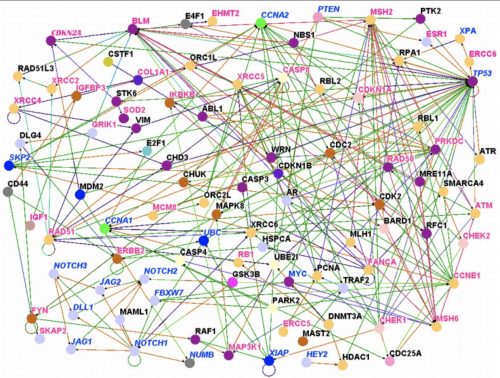

After testing over four million markers, they found several of interest and continued further tests. The study found five genome-wide significant markers for European Americans and one for African Americans. “During post-GWAS analyses, we were able to dig deeply into the biology of the trait,” Gelernter said. They found a gene locus that could also indicate vulnerability to other mental disorders besides anxiety. This provides a possible explanation for the coincidence with other symptoms. “When investigating our GWAS results in the context of other samples, we were able to replicate our findings, which is encouraging for future studies,” Gelernter said. Comparing data from other studies which applied GWAS to a smaller sample, the team was able to correlate many of the markers they found. They were also hopeful that the estrogen receptor gene, which they had specifically identified, would reveal more about the nature of the syndrome. “We do not understand how the estrogen receptor gene is involved in the development of anxiety yet,” Gelernter said, “but it may help explain why anxiety disorders are about twice as common in [biological] females as in males.”

The researchers have started thinking about improvements to the study. “Even though the MVP sample has excellent representation from non-European groups, we still have the most subjects [of] European ancestry. Additionally, the MVP sample, like the veteran population from which it is drawn, is mostly male,” Gelernter said. He hopes that as the MVP sample increases, there will be enough new subjects from different ancestry groups to be able to draw specific conclusions from each group. This would allow them to analyze in greater depth why some genetic risk markers are significant only in African Americans or European American subjects, explore different ethnic backgrounds that are underrepresented in the sample, and dive deeper into the “clear sex difference” in the development of anxiety disorder. Much is left to be discovered regarding the different variations of genetic sources for the disorder, but this will only be possible with greater absolute numbers of subjects from each population group.

Dr. Gelernter is hopeful that in future studies, scientists will be able to thoroughly examine the biology of the markers they found and understand how they may cause anxiety or its co-occurring diseases. Similar to the estrogen receptor gene, the researchers currently know which gene loci are responsible for anxiety disorders, but have not yet elucidated their mechanisms. Furthermore, only about a third of individuals with anxiety disorders actually receive treatment, which is one reason why more accessible and effective pharmacotherapy development is so important. The study could also lead to improved treatments by helping identify target molecules for medicine. It points in a promising direction for the treatment of anxiety, depression, PTSD and other syndromes, eventually relying on more effective psychopharmacology.