Whether it’s roommates, suitemates, or friends, students at Yale are constantly in the vicinity of others. Thus, it’s surprising whenever one person falls ill to viral infections such as the common cold, yet their roommate, who shares their personal space to the greatest extent, does not. Why is that? It is all embedded in a concept of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that fights pathogens, and the response of nasal mediators in the mucosa, the tissue lining the lung.

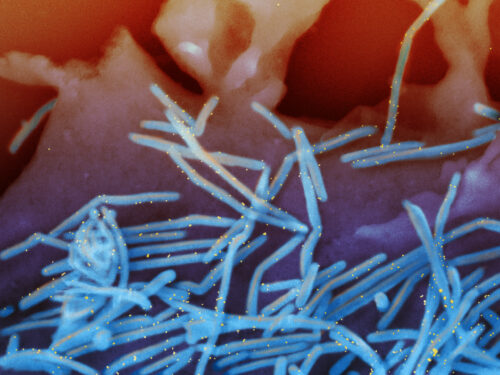

Researchers at the University College London administered fifty-eight participants with the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a cause of neutrophilic lung inflammation, then analyzed the immune cells and proteins in their nasal mucosa. Only fifty-seven percent of the participants actually displayed symptoms of infection. Those infected possessed a neutrophilic inflammatory signal beforehand. After infection, they repressed an early immune response but later released cytokines, cell signaling proteins, that induced inflammation. In contrast, those who were not susceptible to infection had much lower neutrophil levels before infection and had an increased immune response a couple of days after infection. The researchers tested on mice and found a similar correlation: neutrophil response prior to exposure to the virus increased chances of infection.

The researchers propose that their findings might apply to viruses beyond RSV. In the unprecedented times of SARS-CoV-2, where individual responses are also known to vary widely, your neutrophilic inflammation might help determine whether or not you’ll fall sick when your roommates, friends, or family members do.