Image courtesy of Getty Images.

It has been frequently reported that racial disparities persist in COVID-19 mortality rates, but how large are these disparities, and what factors create them? Exactly one year after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, a team of researchers from the Yale School of Public Health, led by graduate student Alyssa Parpia, published a study evaluating how the pandemic has reflected systemic racism in the United States. The study looked at the disproportionate burden borne by Black Michiganians in the COVID-19 pandemic relative to their White counterparts.

Specifically, the team studied mortality attributable to COVID-19. While only 14.1 percent of the Michigan population is Black, Black Michiganians experienced about thirty-five percent of COVID-19 deaths in the entire state as of November 2020. The researchers compared the demographic characteristics—such as age, sex, and total number of comorbidities (presence of more than one illness or disease in one patient)—of White and Black individuals. Even after accounting for these factors, Black individuals were still at higher risk of COVID-19 mortality than their White counterparts, indicating that race is a driving factor behind the disproportionate mortality burden in Michigan.

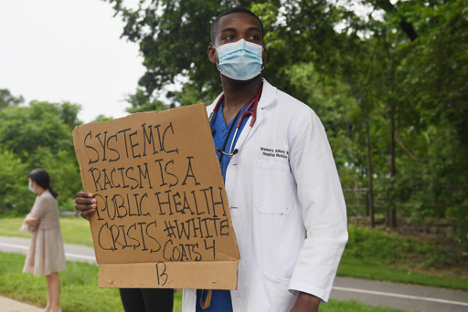

These results shine a light on systemic racism in the United States. The team’s research demonstrated that chronic conditions alone are not responsible for the increased mortality rate among Black individuals, especially for those who are younger. Systemic racism, for one, has created racial disparities in socioeconomic status. And even when socioeconomic status is not a factor, biases and stereotypes have a serious impact on how doctors treat people of color, especially Black individuals. For example, a study conducted by the National Institutes of Health reported that between 2005 and 2016, the admission rate into hospitals was ten percent lower for Black individuals compared to their White counterparts. This can lead to misdiagnosis of illnesses, a lack of proper pain management, and increased health risks in general. Histories of systemic racism have created a lack of trust between medical personnel and racialized populations.

Parpia’s study helps us quantitatively identify racial disparities in the United States, a crucial step toward addressing systemic racism. Stopping the pandemic will not stop the inequalities built by hundreds of years of racially discriminatory and oppressive policies. Parpia noted that there are many other important factors linked with systemic racism that we should continue to explore. Racial inequality in employment presents one such example. As “essential workers,” grocery store or transit employees—positions disproportionately held by Black Americans—have less access to personal protective equipment compared to hospital employees. Many who do not have access to higher paid positions are also excluded from health insurance. In addition, essential workers might not have access to paid sick leave and are less likely to socially distance because of the nature of their jobs.

Race-based socioeconomic inequities and inaccessibility of healthcare have heightened chances of COVID-19 exposure and lowered overall survival rate. “The pandemic magnified many existing issues we had in the U.S., and we should use it as an impetus to change our entire healthcare structure,” Parpia said. Even as the spread of the COVID-19 dies down, it is imperative to examine underlying reasons why certain populations are more at risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 than others. These communities will continue to be more at risk if we maintain the status quo.

Parpia suggested solutions such as providing paid sick leaves, living wages, and universal healthcare, as well as restructuring the U.S. prison system. These supports would help ensure that people are able to adhere to the stay-at-home guidelines put in place to control disease transmission. This, in turn, could have compounding effects. For example, providing paid sick leaves would allow for people to avoid exposure to others when sick, thus decreasing the spread of the virus.

“These should be seen as basic rights, and for some reason, they are not,” Parpia said. And while the proposed solutions center on just one aspect of systemic racism, according to Parpia, they “will have wide-reaching implications on the ability of racialized populations to be able to approach a semblance of equity with White populations in the United States.”

Works Cited

Parpia, A. S., Martinez, I., El-Sayed, A. M., Wells, C. R., Myers, L., Duncan, J., … & Pandey, A. (2021). Racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality across Michigan, United States. EClinicalMedicine, 33, 100761.

Zhang, X., Carabello, M., Hill, T., Bell, S. A., Stephenson, R., & Mahajan, P. (2020). Trends of racial/ethnic differences in emergency department care outcomes among adults in the United States from 2005 to 2016. Frontiers in medicine, 7, 300.