Millions of years ago, long before any of us existed, dinosaurs roamed the Earth. What might have stood where you are right now? Maybe a T. rex or a Triceratops?

If you are somewhere in eastern North America, the dinosaurs that lived near you long ago might be unique. Chase Brownstein, a Yale College junior pursuing the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology major, recently conducted research showing that eastern North American dinosaurs were probably very different from the famous species of the American West. His work sheds light on the possibility of multiple paths to evolutionary success.

Dinosaur Island

During the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs like the T. rex existed, the Earth looked very different from how it does today. Surrounded by oceans and seaways, eastern North America was isolated from the rest of the world for about thirty million years, constituting an island landmass named Appalachia. But since the 1800s paleontologists have largely neglected the study of what kinds of life once inhabited Appalachia.

When organisms evolve on an isolated landmass, it’s considered more likely for them to develop in ways that differ substantially from their relatives elsewhere. This has caused researchers like Brownstein to ask: was this true for dinosaurs isolated in Appalachia, and if so, what unique characteristics did they have? Poor fossil-forming conditions and other factors, however, have made this question difficult to answer.

Firstly, Appalachia has smaller mountain ranges compared to western North America. This means that the shorter rivers created by these mountains don’t flow as far and therefore cannot accumulate as much sediment as their longer counterparts in the West. This accumulation of sediment is what creates fossil-forming regions. Shorter rivers generate fewer of these regions; thus, fewer fossils formed on Appalachia to begin with, making it difficult to know what kinds of dinosaurs lived there. Additionally, the fossils that did form had a high chance of being destroyed later by glaciers. The same glaciers that carved out the Great Lakes dug up much of the fossil-containing sediment in eastern North America.

Finally, it’s difficult to even access the fossils that did survive the glaciers, as the eastern coast of North America is much more densely populated than the West. Most of the land is privately owned. “Nobody wants you to make a giant hole in their backyard,” Brownstein said. Many of the major fossil discoveries that are now in museums like the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History were therefore made in the 19th century, when populations were less dense and eastern fossils more accessible.

Uncovering Clues

In 2015, while browsing collections at the Yale Peabody Museum, Brownstein elucidated connections between two different tyrannosaurs—Dryptosaurus and the Merchantville tyrannosauroid—to answer the question of whether distinct dinosaur species evolved on the once-isolated eastern North America. “This research is the culmination of several years of work into the question of eastern North American biogeography,” Brownstein said.

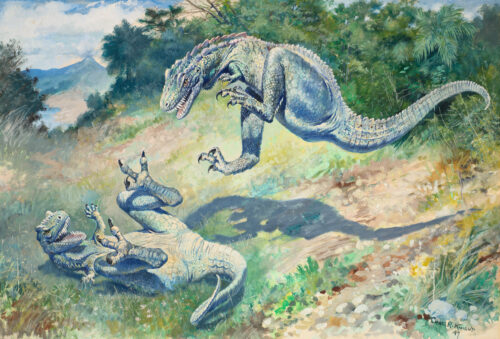

In 1866, West Jersey Marl Company workers discovered the enormous fossil of a dinosaur that lived approximately sixty-seven million years ago in modern-day New Jersey. Yale Professor of Paleontology Othniel Charles Marsh named the dinosaur Dryptosaurus in 1877. Brownstein had the opportunity to study the Dryptosaurus fossil at the New Jersey State Museum. The fossil revealed distinct anatomical features distinguishing Dryptosaurus from other tyrannosaurs like the T. rex. In particular, Dryptosaurus had an elongated skull and hands ranking among the proportionally largest for any dinosaur. Furthermore, it had massive claws reaching up to six inches long and an unusually shaped foot with three bones.

While at the Peabody Museum, Brownstein noticed that the foot of a tyrannosauroid found in the Merchantville Formation in Delaware displayed similar features to that of Dryptosaurus. To investigate, he used the Tree Analysis Using New Technology (TNT) program to conduct a phylogenetic analysis of the Merchantville tyrannosauroid and Dryptosaurus. The program incorporated the skeletal features of the two dinosaur species to determine evolutionary relationships.

From this computational analysis, Brownstein discovered that the Merchantville tyrannosauroid and Dryptosaurus evolved from a common ancestor and are part of the same clade. That clade, known as Dryptosauridae, is a distinct group of tyrannosaurs that existed solely in Appalachia. For over a century, paleontologists have hypothesized the existence of a distinct set of tyrannosauroids native to the once-isolated eastern North America. With Brownstein’s research, we now have evidence supporting that hypothesis.

Though factors such as poor fossil records still constitute obstacles to our knowledge of the dinosaurs that inhabited the east, Brownstein’s research underscores the rise of anatomical differences in the dinosaurs of eastern and western North America. In a broader context, such discoveries highlight the profound interplay between geographical isolation and the evolution of species.

Searching for History

Evolutionary biologists and paleontologists often develop “just-so stories,” speculative explanations for the origins of a biological trait. The term comes from Rudyard Kipling’s 1902 “Just So Stories for Little Children.” The book includes a collection of animal tales such as “How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin,” in which the rhinoceros developed wrinkles after rubbing against a tree. In the context of dinosaurs, there are many speculative hypotheses that tyrannosaurs evolved a specialized skull, superior sight, or other specific traits to achieve supremacy. The T. rex—the “King of the Dinosaurs” that lived in western North America—boasted hallmark features of dinosaur superiority, such as a gigantic skull, forceful jaw, powerful hindlimbs, and muscular physique. Yet, whether those features are indeed necessary for biological success remains up for debate.

The eastern North American Dryptosaurus, for example, differed from the T. rex and other tyrannosaurs: it had larger hands, extensive claws, and a distinctive unit of foot bones. “Eastern North American tyrannosaurs were really big, were probably predators, and had a different set of features than western North American tyrannosaurs,” Brownstein said. “This may cause us to rethink the hypothesis that there was only one way that tyrannosaurs got so big and successful.” In this way, Brownstein’s discoveries point towards the possibility that tyrannosaurs achieved success through the evolution of differing features.

As Brownstein emphasized, his research raises broader questions of evolution that demand further research and contemplation—the prevailing one among them being: how many paths could there be to evolutionary success?

To find out more about eastern North American dinosaurs, the next step would be to discover a more complete skeleton of these species. Currently, research is limited to the fossils that have already been found, which do not include the body part that paleontologists consider to be the most informative: the skull. However, looking at living things today could also shed light on the nature of extinct species. Analyzing the characteristics of dinosaur descendants can sometimes help us learn more about their ancestors.

Behind the Discoveries

Brownstein—who has an impressive research history, having published about twenty peer-reviewed articles in journals including Royal Society Open Science, the Journal of Paleontology, Scientific Reports, and the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society—intends to go forward with other research while he waits for more fossil discoveries. He is currently studying fishes with Yale Professor and Chair of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Thomas Near.

Brownstein said that he was fortunate to have access to fossil collections like those at the Peabody Museum and described his appreciation for those who have provided support and advice in his research endeavors. “I have been very fortunate to have people who gave me a chance,” Brownstein said.

Brownstein has a genuine passion for the field of research. “I have always been really fascinated with nature, time, what lived before, and how we got here,” he said. Research simply makes him happy. “If I want to do something that I enjoy, I will do research, write, and study things,” he said. Based on this passion, Brownstein described science in the larger context of the human desire for exploration. “It is a human thing to constantly explore. The urge to discover is a motivator in science, and it’s a beautiful thing,” he said.

Just like we push the boundaries of our universe with space travel, we are now pushing the boundaries of time by uncovering our planet’s incredible history. In Brownstein’s case, we now understand that the geographical isolation of eastern North America over the course of thirty million years likely provided the means for the evolution of distinct dinosaur species.

As we continue to uncover our planet’s incredible history, what will we discover next?

About the authors:

Elisa Howard is a sophomore neuroscience major in Berkeley College. In addition to writing for YSM, she volunteers at CT Hospice and Yale Community Kitchen, constructs 3D-printed limb devices through Yale e-ENABLE, and helps organize blood drives for the American Red Cross at Yale. During the summer, she researches neural repair in the Strittmatter Lab at the Yale School of Medicine.

Anavi Uppal is a sophomore astrophysics major in Pierson College. In addition to writing for YSM, she is one of Synapse’s outreach coordinators, and she teaches science to elementary schoolers through Yale Demos. She’s also a fall social media intern at NASA Ames Research Center.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Chase Brownstein for his time and enthusiasm about his research.

Extra reading:

Doran Brownstein, C. (2021). Dinosaurs from the Santonian–Campanian Atlantic coastline substantiate phylogenetic signatures of vicariance in Cretaceous North America. Royal Society Open Science, 8(8), 210127. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210127

Marsh, O. C. (1896). The Dinosaurs of North America. Govt. Print. Off.