During the Great Depression in 1929, immigrant workers became scapegoats for economic hardship, accused of taking jobs away from native-born Americans. After the tragedy of 9/11, many people grew fearful that their lifelong Muslim neighbors could somehow be implicated in the terrorist attacks. Such crises have historically caused individuals to see others as a threat. Drastic changes tend to make people more paranoid.

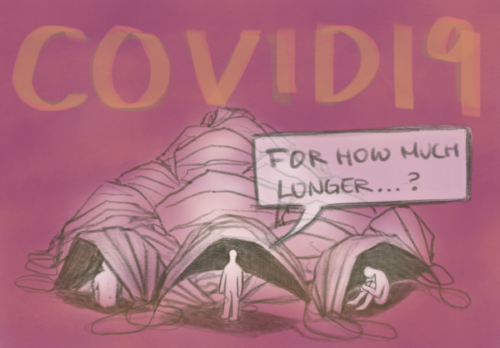

This trend continues with the COVID-19 pandemic. Toilet paper stock quickly ran out as shoppers rushed to acquire household supplies as if in a post-apocalyptic frenzy. Asian Americans experienced an exponential increase in hate crimes due to fringe conspiracy theories regarding the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Differing opinions on mask-wearing have turned into heated, politicized debates. Everyone seemed to share a heightened sense of apprehension about the future.

Yale Cognitive Research Scientist Praveen Suthaharan, Associate Professor of Psychiatry Philip Corlett, and their team recently published a study in Nature Human Behavior about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals’ paranoia. To these researchers, the widespread uncertainty caused by the pandemic provided an unprecedented opportunity to track the impact of an unfolding crisis on human beliefs.

A Pandemic of Paranoia

Constantly wearing a mask to protect each other from a virus we cannot even see with our own eyes, against a disease that is in many cases asymptomatic, can be overwhelming—enough to put anyone on edge. Previously mundane activities, like going to the grocery store or visiting grandparents, now draw concerns: just by doing them, one could contract or transmit a potentially fatal disease.

The study’s authors saw that paranoia significantly increased throughout the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, with self-reported paranoia levels peaking as states drew closer to reopening. Overall effects on other mental illnesses were also negative. “We have all experienced challenges since the onset of the pandemic, and we also noticed this in our data: that over time, depression and anxiety increased during the lockdown,” Corlett said.

Ensuring that the general public remains calm and willing to work together is essential to overcoming a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in efforts like vaccination and social distancing. While many have argued for and against the merits of mandatory lockdowns, this study’s data demonstrate that divergence in state-level response correlated with differential increases in paranoia—both self-reported and measured via laboratory tasks. Vigorous, proactive lockdown policies were associated with less paranoia when compared to lax lockdown policies. One may similarly expect to see different outcomes based on states’ varying mask mandates, Corlett posited.

To Mask or Unmask

Over a year into the pandemic, wearing a mask while around others should seem like a no-brainer. Masks are cheap, effective, and easy to wear. Suthaharan’s team was interested in understanding why so many people were and are still opposed to wearing a mask, despite the seemingly clear cost-benefit analysis for doing so. “It’s similar to when you see a patient smoking a cigarette outside of the hospital,” Corlett said. “We wanted to understand why people engage in behaviors risky for their health.”

In their study, the researchers found that paranoia was highest during reopening in states that required mask-wearing. This supports the notion that, in social settings, humans are “conditional cooperators”—we tend to follow rules as long as we perceive others doing the same. As soon as this is no longer true, we tend to stop following these rules. As the data suggested, when there was a mask mandate but people saw others without a mask, that raised confusion and paranoia. In fact, individuals with paranoia were far more reluctant to wear masks and reported wearing them significantly less.

Suthaharan wanted to know whether mask mandates themselves could have contributed to the increased mental health issues experienced during the pandemic. To that end, his team performed a type of analysis called “difference-in-differences,” which allowed them to infer causal relationships by comparing changes in paranoia levels in states that implemented a mask mandate to states that did not, or only recommended it. The analysis revealed that mandated mask-wearing was associated with a forty percent increase in paranoia levels.

These results could be connected to a lack of clarity in public health messaging, Corlett conjectured. Early in the pandemic, health organizations such as the CDC and WHO did not fully support masking, even claiming inefficacy at times. Later, emerging evidence supported a reversal in opinion, which in turn led to mask shortages and induced worries among people who were now unsure about whether they would be able to get masks.

The uncertainty and paranoia caused by mask mandates possibly led to distrust of public health organizations as mask-wearing became a politicized topic. “In no other time in history have we experienced a pandemic this problematic, and instead of dealing with it as a community of like-minded people, what we’ve done is double down on our differences,” Corlett said.

All in this Together

If there is any comfort to be taken by those who have experienced mental health difficulties since the start of the pandemic, it is that nobody is alone in their struggle. With this collective aspect in mind, Suthaharan and his team were keen to study group-level cognition to see if characteristics and experiences shared by a population affected mask-wearing or paranoia.

Using an index of cultural tightness and looseness, developed by psychologists at the University of Maryland, to measure a state’s cultural tolerance for rule-breaking, the researchers found that stricter states that mandated mask-wearing experienced the lowest rates of mask-wearing. Individuals in culturally tight states may have grown paranoid seeing others without masks, leading to overall lower levels of mask-wearing in these states. Fear of social reprisal due to anti-mask sentiments may have further driven their paranoia.

Many of those who were hesitant to wear a mask were also hesitant to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, with unproven conspiracy theories circulating about its development and its usage in government surveillance. The research team found that paranoia was significantly correlated with belief in these specific conspiracy theories, as well as belief in other theories, such as that prominent Hollywood entertainers are involved in child trafficking.

These results demonstrate that our surrounding culture and environment can substantially affect mental health. “It was very interesting and informative to show that group-level characteristics such as rule-following and cultural tightness impacted peoples’ behaviors and beliefs,” Corlett said.

Cognitive Origins

The Corlett lab has been interested in studying the origin and neural mechanisms of paranoia for several years—even before the pandemic. Notably, within the field of psychiatry, there are mixed opinions regarding the origins of paranoia in the mind and brain. Some believe that the brain has a distinct module for dealing with social relationships and that problems with this part of the brain cause paranoia. Corlett, on the other hand, contends that the same reward mechanisms in our brains that tell us whether we like things, such as different types of food or even money, are implicated in paranoia. To him, we do not differently process positive or negative feelings towards something in social versus nonsocial settings.

In this study, the authors conducted two types of experiments to assess paranoia: social and nonsocial. In the nonsocial task, participants were instructed to choose between three cards that each had a different probability of being “correct.” They were also told that the underlying probabilities would change, but not how often or when. A paranoid individual would likely switch their choices more frequently, even after positive feedback (“win-switching”), incorrectly attributing probabilistic errors to a shift in underlying probabilities. In the social task, instead of using cards, individuals were told they could collaborate with one of three individuals who would either help or hurt them.

The researchers found that the win-switching frequency in the nonsocial task was indeed significantly correlated with paranoia, validating that performance on the task was an accurate measure of one’s paranoia levels. More importantly, they also found that there was no difference in behavior between the social and nonsocial tasks, suggesting that Corlett’s theory may offer a more valid and accurate understanding of paranoia’s origin.

Interestingly, participants in this study performed the same tasks before and during the pandemic, yet yielded starkly different outcomes in each condition. This may shed light on the replication problem in psychological research, where many published findings cannot be reproduced by other researchers. It is possible that some of these findings could be merely artifacts of changing real-world conditions between replication attempts. But even so, this study suggests that real-world changes can have profound impacts on individual behavior in laboratory tasks.

An Informed Future

This study could have many implications for the field of psychiatry, and the authors hope that its insights into human psychology will help those struggling with mental illness. They also hope that their research will affect positive change for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Given how paranoia affects individual responses to worldwide crises, the study’s results could help guide future decision-making and inform effective communication between the public, governments, and other organizations.

“Conducting online research during a pandemic was a challenge, but also inspiring,” Corlett said. “It is unusual to be so connected to real-world events and to study them as they unfold, and for our data to have implications for how the situation could be handled differently now, and in the future.”

About the Author

Shudipto Wahed is a sophomore in Benjamin Franklin from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania interested in studying Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry. Shudipto conducts research on protein engineering in the Ring Lab at the Yale School of Medicine. Outside of YSM, Shudipto is a senator for the Yale College Council and an analyst in the Yale Student Investment Group.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Philip Corlett for his time and enthusiasm.

Extra Reading

Reed, E. J., Uddenberg, S., Suthaharan, P., Mathys, C. D., Taylor, J. R., Groman, S. M., & Corlett, P. R. (2020). Paranoia as a deficit in non-social belief updating. ELife, 9.