Unless you’re sitting at the dinner table or browsing through the grocery store aisles, chances are you’re not thinking about mollusks, the group of animals that includes clams and squid. Yet, for paleontologists like Mark Sutton, Julia Sigwart, and Derek Briggs, two newly described specimens, Punk ferox and Emo vorticaudum, could not be more worthy of attention. The newly described species rocked the researchers’ minds and bridge the gaps defining their field’s current understanding of mollusk evolution. “[Mollusks] are the second most diverse group there is—they’re one of the major branches of life, but we don’t know as much as we’d like to,” Sutton said. Part of this knowledge gap comes from preservation bias, a bias in archaeological research arising from how hard stuff, like shell and bone, preserves more easily than soft tissues. “[Punk and Emo] are all soft; they would decay away pretty swiftly,” Briggs said. The conditions required for preserving the soft, nearly shell-less Punk and Emo were improbably perfect.

Luckily, improbable doesn’t mean impossible. All it takes is a quarry, a concretion (a spherical encasement of volcanic ash around the size of a baseball), and the right split to reveal a crystallized creature. In the case of Punk and Emo, the lucky spot was the Silurian Herefordshire Lagerstätte, a quarry bordering England and Wales known for its concentration and quality of fossils specimens. Upon splitting the concretion, Sutton and Briggs were astounded by what they saw—but there was a bigger surprise to come.

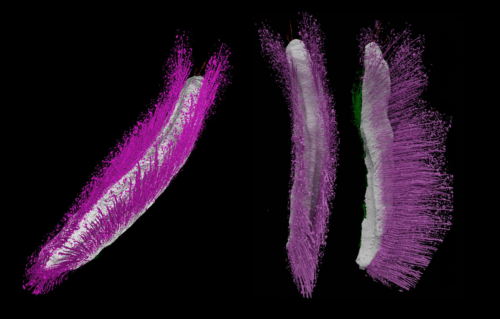

Both specimens were scanned using phase-contrast synchrotron X-ray scanning tunneling microscopy at a synchrotron in France. Computer-aided scanning with a synchrotron is a relatively new method that isn’t effective for all specimens, but it was particularly useful for Punk and Emo. The method relies on detecting the differences in density between the object of interest and the material that surrounds it. Unfortunately, it isn’t always a feasible method for every fossil. “The problem with this is that the mineral filling the cavities is essentially the same as the mineral that cements the concretion,” Briggs said. As a result, both specimens were also processed with a technique known as physical-optical tomography and photography. Both concretions were ground into thin layers for analysis. Unlike the synchrotron scans, tomography results in the destruction of the fossil. In the end, the synchrotron data were used to reconstruct 3D models of Emo, while the physical-optical data was used to reconstruct Punk. This revealed a combination of never-before-seen morphologies, including a multitude of spikes reminiscent of the late 1900s punk rock aesthetic.

“The whole animal surprised me!” Briggs said. Sutton elaborated on the startling discovery. “Every individual thing we’ve found there, we see on another mollusk. But combinations are what’s weird,” Sutton said. For example, the end of Emo has swirled spines resembling modern-day worm-like mollusks known as aplacophorans, but the rest of the body is spineless and lightly shelled. This suggests that Emo and other mollusks like it may serve as the “missing links” between mollusks of ancient times and the shellfish we see today.Overall, the unusual morphologies of Punk and Emo provide insight into the true diversity of mollusks, specifically the less familiar aculiferans. As Sutton and Briggs look into the future, they hope to find more unusual mollusks to clarify the lineage’s evolution. “The fact that adding these two new things complicates rather than simplifies the picture is probably a sign that we’re only scratching the surface diversity of the group,” Sutton said.