Men chase. Women choose. For decades, this has been the mantra of evolutionary biologists. Feminists may balk at the idea, but the logic is not so difficult to comprehend: For most species, the female sex has a higher parental investment and therefore has an interest in choosing a good mate. In humans, the female invests nine months in pregnancy and during this time will be nurturing a single offspring by a single male, whereas the male is potentially able to have multiple offspring by different mothers. In order to be selected as a mate, however, the male must convince the female that he is worth the long pregnancy that will ensue. From this theory, scientists explain the brilliant feathers of male peacocks, the antlers of stags, and the manes of lions.

But as far as one species of butterfly is concerned, the mating world is a little more equal. Katie Prudic, Ph.D., a member of Assistant Professor Antónia Monteiro’s lab at Yale University, discovered that the butterfly Bicyclus anynana exhibits changing sexual roles depending on what time of the year it is conceived. Found in many areas of Africa, the butterfly exists in two distinct forms: one for the dry season and another for the wet season.

Two Forms: Morphological and Behavioral Changes

In the wet season form, the eyespots are large and an apparent transversal band appears on the underside of the wings. The dry season form has eyespots of greatly reduced size and cryptic ground coloration, a type of color mimicry that allows the animal to blend into its environment. The phenotypic differences between the two forms lie solely in the temperature of the larval rearing, not any genetic differences. This phenomenon is known as phenotypic plasticity, but the mechanism by which these butterflies sense the temperature difference and the specific changes regarding protein synthesis are still unknown.

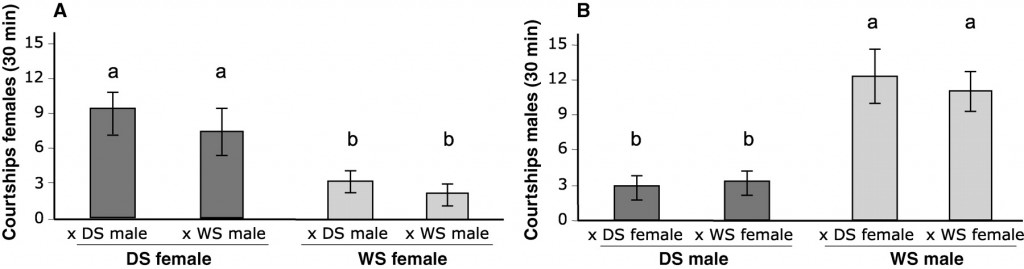

In the wet season, mating follows the path of most other species. The males chase, the females choose. However, Prudic discovered that during the dry season, the females took control and began to court males. This courtship behavior involves a courter displaying its dorsal eyespots to a receiver by rapidly opening and closing its wings. It was previously believed that these dorsal eyespot pupils were uniform between the sexes and seasonal forms of the butterfly. However, Prudic’s research indicates that a reciprocal phenotypic change occurs between the seasonal forms of the male and female butterfly. “They don’t immediately appear to be modified; they seem about the same size. But they are actually different,” said Monteiro. The central white spots on wet season males’ eyespots have greater light reflectance and are greater in size than those of the dry season males. Likewise, the white spots of dry season females have greater light reflectance than those of the wet season females.

Temperature Shifting Costs and Benefits

This changing behavior is the result of the shifting relative costs and benefits of mating for each of the sexes during the two seasons. When Prudic examined the longevity and fitness of mated and unmated developmental forms, she discovered that females that mate with dry season males have a much greater life expectancy and lay more eggs than those females that mated with wet season males or did not mate at all. On the other hand, she discovered that the life expectancy of dry season males who mate with dry season females was much lower than the life expectancy of wet season males who mate. In other words, on average, dry season females that mate increase their life expectancy and fecundity, and dry season males that mate have shorter life expectancies. In the dry season, the male thus incurs a greater parental cost, whereas the female seeks to reap the benefits that mating provides. Now, the female gets to chase, and the male gets to choose. However, Monteiro cautions, the change in fecundity monitored in the lab may not actually play out in the field.

In the field, females in the dry season are probably delaying laying their eggs until the end of the dry season, whereas the wet season females immediately lay their eggs after mating. The ovaries of the females in the dry season are not developed until just before the rains begin to fall, marking the start of the dry season. While the exact reason for this late development is unclear, it is likely due to resource limitations that make it most advantageous for the butterflies to release their eggs at the start of the wet season. Instead of mating and laying her eggs, the female receives from the male a “sperm packet,” called a spermatophore, which carries spermatozoa (motile sperm cells) and nourishment. This nourishment is key to the changing sexual roles of the wet season and dry season forms of Bicyclus as well as the difference in longevity and fitness.

In the dry season, the spermatophores that are deposited in the female have a yet unknown quality that makes females live longer lives than those that live in the wet season and recieve spermatophores from wet season males. Bicyclus thrives upon fruit, and far fewer natural resources are available to the butterflies during the dry season. “These spermatophores presumably help females survive through the very lengthy dry season,” notes Monteiro. By giving up important nutrients or other costly substances, the male butterfly incurs a cost of reduced life expectancy and fitness. The females, on the other hand, hold on to those substances for up to six months, using them to survive until they are able to lay eggs. The cycle continues, with wet season males courting females, and dry season females courting males.

New Directions for Research

These findings on the changing mating practices of Bicyclus present further questions to be explored. It is unclear what nutrients spermatophores contain and how the act of depositing the spermatophores incurs a cost in the male butterfly. Little research also explores why the receiver prefers to be courted by a partner with larger dorsal eyespot centers that exhibit greater light reflectance. Further, because the forms of Bicyclus are temperature-dependent, drastic changes in the environment may fundamentally alter the butterfly’s behavior. “If something changes in the environment (and it is very likely with global warming) or if something changes about the resources available in the environment, the selection pressures on the butterflies will also change,” argues Monteiro. Sometime in the near future, Bicyclus anynana may not exhibit this practice of changing sexual roles. For now, researchers in the Monteiro lab continue to explore the mechanism of phenotypic plasticity in Bicyclus with the hopes that one day humans may understand the nuances of this remarkable feature of the natural world.

About the Author

Lara Boyle is a junior in Branford majoring in Biology with a focus in Neurobiology. She is the Outreach Chair for the Yale Scientific Magazine and works in Professor Glenn Schafe’s lab studying the epigenetic mechanisms that regulate the formation of long-term memories.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Antónia Monteiro for her time and enthusiasm about her research.

Further Reading

A. Berglund, M. S. Wideo, G. Rosenqvist, Sex-role reversal revisited: Choosy females and ornamented, competitive males in a pipefish. Behav. Ecol. 16, 649 (2005).